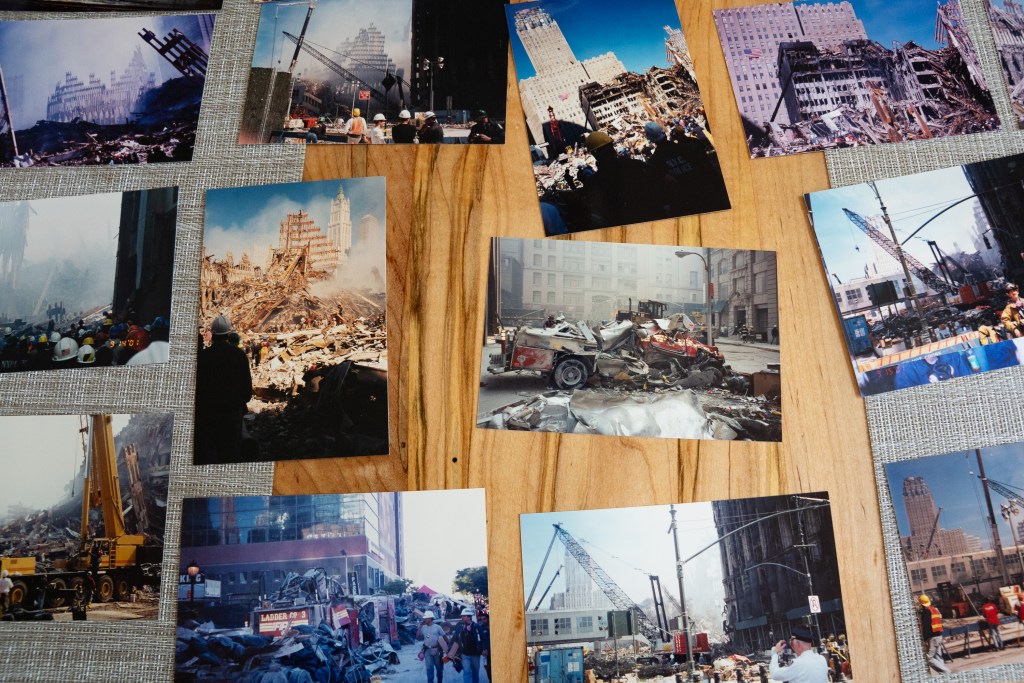

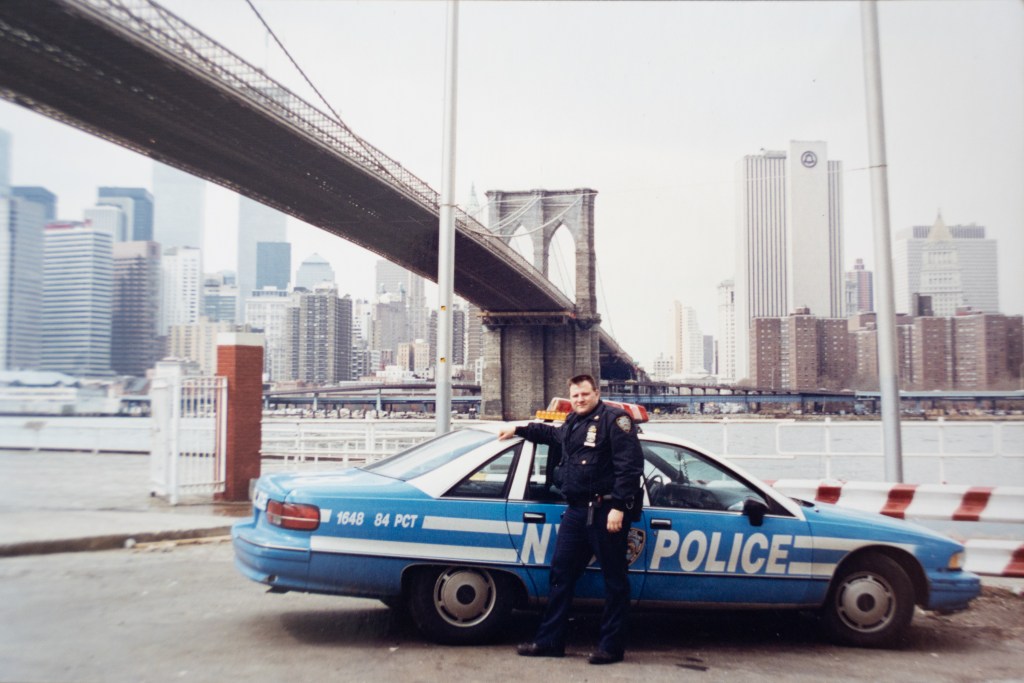

Clayton resident Harold Delancey was working for the New York Police Department on September 11, 2001.

Delancey says he is haunted by memories of the Twin Towers falling and the work he had to do around Ground Zero that day, and in the weeks afterward, as a first responder. Nearly 25 years later, he is treated for post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health issues, as well as COPD. In July 2023, Delancey had his prostate removed at WakeMed following a cancer diagnosis.

As a medically certified member of the federal World Trade Center Health Program (WTCHP), it should be easy for Delancey to receive the free coverage he’s entitled to for his treatment. But after moving to North Carolina in 2013, with 20 years of service to the NYPD under his belt, Delancey says accessing and paying for health care here has been anything but easy. And it could get even harder for him and 9/11 survivors across the country if Congress doesn’t continue to fund the program that provides them free health care, or makes further cuts to the agencies that administer it, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Right now, the WTCHP faces a $3 billion shortfall and more than $1.2 billion in CDC cuts because of a federal restructuring of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

“I got sick because I had to go to work,” Delancey says. “I didn’t have a choice in the matter. I had to show up for work.”

Delancey is one of more than 2,000 North Carolina residents who are certified and enrolled in the WTCHP, and North Carolina is fifth for the number of enrolled members across all 50 states, behind New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Florida.

Those residents include first responders like Robert Young, another former NYPD officer who now lives in Graham and has to travel up to New Jersey every year for treatment.

They include people like James Stack from Apex, a former laborer who was sent into a building in Lower Manhattan two days after the 9/11 attacks. Stack has since been diagnosed with three different kinds of cancer.

And North Carolina’s 9/11 survivors include residents like Lorraine Meehan of Apex, who watched the towers fall from her office directly across West Street.

“[These residents] need the protections of the World Trade Center Health Program, just like the people from New York,” says Michael Barasch, a 9/11 survivor and attorney whose firm, Barasch & McGarry, has recovered billions of dollars for 9/11 victims, survivors, and their families. Barasch is currently traveling up and down the East Coast, meeting with survivors to encourage them to reach out to their congressional representatives and lobbying lawmakers themselves to adequately fund the WTCHP in the upcoming “big beautiful” budget and reconciliation bill.

“There were people from all 50 states who responded in New York, and New Yorkers retired to all of those 50 states as well,” Barasch says. “They all promised they’d never forget. Every politician loves to say it.”

On a scorching Monday afternoon in early June, more than two dozen retired police officers, EMTs, firefighters, office workers, teachers, utility workers, and veterans are seated in the ballroom at the Renaissance hotel in North Hills. All WTCHP enrollees and their families, they’re listening to Barasch make his pitch to them about calling their congresspeople to impress upon them the importance of fully funding the program.

Barasch is describing how, five days after 9/11, Wall Street reopened, and not long after that, people came back to work and school, including to Stuyvesant High School (which was used as a morgue), New York Law School, Pace University, and some 20 elementary schools south of Canal Street, all blocks from the World Trade Center site.

On September 18, then–EPA administrator Christine Whitman publicly announced that the air in Lower Manhattan was safe to breathe, a statement that was determined to be untrue.

Following Barasch’s remarks, Lorraine Meehan tells me about her experience on 9/11. She was working as an HR manager at 2 World Financial Center, just across the street to the west of the Twin Towers.

“I worked on the fourth floor,” Meehan says. “I heard the first plane hit. I rushed to the window facing that tower. My most clear memory was a woman, literally on fire. She was running towards [West Street]. I watched fire and EMS and … the fire department and the police pull up, people running into the building, with all their hoses and their equipment and no hesitation, chunks of the building falling down.”

Meehan says she went back to her seat and saw the second plane hit above her.

“The sky went black, and there was all this paperwork that seemed to have been shredded, it was like a snowstorm,” she says. “People screaming, and pandemonium. We were evacuated not long afterwards. We were told to wait in the marina behind my building, and there, we watched the injured come through.”

But more than her own experiences that day, Meehan tells me she thinks of her husband, John, a federal law enforcement officer with the Department of the Interior who was deployed to recover the bodies of the dead from the rubble. John, who suffered various respiratory conditions including RADS and COPD, was enrolled in the WTCHP for over a decade before he died during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“About two years [after 9/11, John] developed symptoms from his exposure,” Meehan says. “That impact is immeasurable in somebody’s life.”

In 2010, the James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act established the World Trade Center Health Program and reauthorized the September 11th Victims Compensation Fund. President Obama signed it into law in January 2011. The WTCHP, which has about 131,000 members currently enrolled in the United States, is administered through two agencies under the federal HHS: the CDC and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), a research agency within the CDC.

James Zadroga, who died at age 34 in 2006, was an NYPD officer who responded to the 9/11 attacks and developed a respiratory illness that his doctors linked to his exposure to toxic chemicals and dust at Ground Zero. He was one of Barasch’s clients.

“When they did the autopsy, they found ground glass in [Zadroga’s] lungs as well as asbestos, lead, benzene, all these known carcinogens,” Barasch says. “And that was the evidence that doctors at [NIOSH] needed, to link all these respiratory illnesses that guys were suffering from.”

Before he died, Zadroga had received some compensation from the federal government from the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund, established for people—and their surviving family members—who were injured or killed in any of the 9/11 attacks, including those at the Pentagon and the downed United Airlines Flight 93.

The Victim Compensation Fund was reauthorized under the Zadroga Act and expanded to include anyone with medically certified 9/11-related health conditions, especially those developed from exposure to toxic dust and other chemicals at Ground Zero. To date, a host of illnesses, including respiratory illnesses like asthma, COPD, and rhinosinusitis, gastrointestinal issues such as GERD, mental health issues including PTSD and depression, and some 60 different types of cancers, are linked to that exposure.

Apex resident James Stack has been diagnosed with three of those types of cancers. Two days after 9/11, Stack, a laborer, was sent into what was known as the 140 West New York Telephone Company (now the Barclay Vesey building), two blocks north of the World Trade Center site, for debris removal and cleanup.

“We were down there seven or eight months, then pulled out, and sent back again,” Stack says. He speaks in a soft voice with a heavy Irish accent.

In 2012, while working on the World Trade Center station transportation hub, Stack was injured on the job. Along with broken bones, his doctors found thyroid and kidney cancer.

“I had enough time for the Laborers’ Local 79 [union], so [I] retired,” Stack explains. He and his wife, Margaret, relocated to North Carolina, where they’ve lived in pretty good health thanks to the WTCHP—until last November, when Stack was diagnosed with prostate cancer.

“If he didn’t get hurt, it would have been too late when they found the cancer,” Margaret Stack says of her husband, who is tall and uses a cane to walk. “He was in ICU, and they said we could put bones back together, but they really needed to get the cancer.”

In 2015, President Obama signed a bill reauthorizing the WTCHP and extending it for 75 years, until 2090. In 2019, following a pressure campaign from 9/11 survivors and championed by the comedian Jon Stewart, President Trump signed a bill raising the benefits for newly enrolled 9/11 responders and certified-eligible 9/11 WTCHP survivors from $25,000 to $75,000.

But this year, in the first few months of Trump’s second term, the U.S. health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and billionaire Elon Musk cut HHS’s workforce by about a quarter, or some 20,000 positions, which included a 20 percent staffing cut to the WTCHP and the termination of 16 doctors and nurses.

The bipartisan backlash was swift, and those positions were reinstated in February, only for a second round of cuts in April to eliminate another 16 staffers. Dr. John Howard, the WTCHP’s longtime leader, was terminated in the April round of cuts. He, along with the 16 staffers, were again reinstated following a bipartisan outcry—but only on a temporary basis.

Living outside of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut creates another layer of hardship for many 9/11 survivors. And recent cuts to NIOSH have exacerbated the issue.

Former NYPD officer Robert Young did rescue and recovery at the World Trade Center site for two weeks after 9/11, “digging up on the pile.” Then, he ran a security detail around the perimeter of the site out of Stuveysant High School. Then he was assigned to set up offices for the newly emerging Joint Terrorism Task Force.

“I was involved with it from the start to finish,” he says. “I was there when that second building fell, and didn’t leave kind of until that investigation was completely done.”

In 2008, Young moved to Graham, where he found it more difficult to access care than it was in the Tri-State area. Now, he travels to Rutgers University to receive treatment for rhinosinusitis and other conditions linked to exposure to dust and chemicals at the World Trade Center site.

While not ideal, Young is OK with making the trip, and by accessing the health care up north he’s been able to avoid some of the issues that fellow 9/11 survivors living in North Carolina have had to contend with.

“I’ve got five of my members in the [USOA Local] 1013 in Raleigh that are in collection,” Young says. “That’s how bad it is, OK, they are in collection from hospitals.”

Delancey, the Clayton resident and former NYPD officer, has experienced some of these issues. In 2022, the WTCHP transitioned its nationwide provider network from Logistics Health Incorporated (LHI) to MCA-Sedgwick. It has not been a smooth transition, Delancey says.

“It’s a lousy, lousy company,” Delancey says. He’s still trying to get his prostate surgery from 2023 and follow-up doctors’ visits covered. Unlike Young, he doesn’t want to travel back to New York every year to get the health care he needs.

“I moved away from New York for a reason, and I don’t really want to go back,” he says. “And it brings back a lot of memories, because, you know, the towers, and it just triggers some emotion.”

These issues aren’t unfamiliar to Barasch. Anyone in the WTCHP who isn’t living in the New York area has to go through Sedgwick for referrals, claims processing, provider network management, and member communications. NIOSH, the CDC’s worker arm, oversees the nationwide provider network for the WTCHP, and following the DOGE cuts to the CDC and NIOSH, its managing relationship with Sedgwick has become more frayed.

“Mr. Musk took a blow torch to NIOSH, so I don’t know who’s in charge of it, I don’t know who to complain to anymore … about Sedgwick,” Barasch says. “I can just hope that if I keep putting pressure on them, through NIOSH or whatever’s left of it, through the World Trade Center Health Program, through my clients, that eventually [Sedgwick] will lose the contract, or they’ll make improvements. I want to see the government select a much more responsible and empathetic carrier when the Sedgwick contract is over, but right now, it’s the devil we know.”

Barasch worries that cuts to the WTCHP, a total amount of about $1.2 billion, will be made permanent in the budget bill that’s currently in the U.S. House. This is why he’s lobbying senators and congresspeople—including North Carolina senators Thom Tillis and Ted Budd—to support the WTCHP.

“What could be more bipartisan than this?” he asks. “Because let’s face it, those toxins didn’t care if you were a Democrat, Republican, New Yorker, North Carolinian, Black, or white. It affected everybody the same.”

The INDY reached out to Senators Budd and Tillis for comment for this story but did not receive a response before our deadline.

Even if the cuts to the program aren’t made permanent, medical inflation and new enrollees mean that the WTCHP needs to be funded at higher levels—$150 million more per year—than it has been in the past. So far, funding hasn’t been included in the bill, and with the July 4 budget deadline looming, it’s not clear if it will be. If the program continues to be funded at current levels, Barasch says, it won’t be able to accept new patients after 2027.

“Well, I don’t think people are going to stop getting sick in 2027,” Barasch says. “I am signing up and putting into the health program over 100 new people every week, and I lose two clients a day to the 9/11 cancers. So we, the 9/11 health program, need this additional funding.”

Along with getting more eligible people into the program or care, Barasch says he’s been fighting a battle in Washington, D.C., to get funding included in the budget bill. If it’s not, there’s another chance for lawmakers to include the money in the national defense budget that’s coming up in September, if they can muster the political will to do it.

“Nine-eleven didn’t end on 9/11 and people continue to get sick every day,” Barasch says. “We need to take care of these people. We gave them a pledge never to forget that the government lied to these people, telling them the air was safe. So we owe this duty to them to provide the health program that we promised them. Let them know it’s not too late.”

Send an email to Raleigh editor Jane Porter: [email protected]. Comment on this story at [email protected].