If Mayor Leonardo Williams is Durham’s ringmaster, then a new convention center might be his big tent. At his 2024 State of the City address last April, Williams described something more than a convention center only frequented by out-of-towners attending conferences.

“We must envision paths to energize Durham’s economy downtown and community-wide,” Williams said in the speech. “We need to invest now in projects that build the kinds of opportunities and features that continue to make Durham a great place to live, work, and visit. These decisions require the foresight to collectively envision the type of community that we’d like to become.”

Williams, always looking for new ways to sell the public on his ideas, is marketing the project as an “innovation center” that would offer modern amenities for local residents and visitors alike, generating revenue while benefitting surrounding businesses. The mayor and his allies see downtown Durham’s next big capital project as much more than a traditional convention center, rather as a way to differentiate Durham from peer cities.

Marquee capital improvement projects make a splash. Politicians could solidify their legacy by putting their stamp on an eye-popping sports arena or convention center. But not everyone is sold that a new convention center will have the transformative effect on downtown that Williams hopes. These projects take time and significant investment, and there’s no guarantee the ground-breaking would come in time to help businesses that already struggling, or that Williams will still be in the mayor’s seat. Can Williams and his allies make the case that the convention center’s big splash will have the desired ripple effect?

The Durham Civic Center, as it was originally known, and the adjoining Omni Hotel were originally built in 1989. Both my parents and my Oma worked at the hotel when it opened. Durham was still suffering from an economic downturn after the tobacco industry collapsed. Local officials set out to revitalize downtown with the civic center and hotel as the anchors.

But downtown Durham remained desolate. Shopping malls were hollowing out commerce in city centers across the country. At the turn of the century, city and county officials collaborated with the private sector, resulting in an explosion of redevelopment that included the American Tobacco Campus in 2006 and the Durham Performing Arts Center in 2008.

The convention center was no longer a centerpiece of downtown’s attractions. These days, unless you’re planning a trip to the convention center, you’d probably miss it. The outside of the building, which nests between the Marriott hotel and Carolina Theatre on Foster Street, is nondescript and gives passers-by few hints as to what’s happening inside.

In 2024, the center held over 136 events, ranging from big ticket activities like Full Frame Documentary Film Festival and NC Comic Con, to quinceañeras and graduations. Two-thirds of the events hosted at the convention center were locally based, says Susan Amey, CEO of Discover Durham. But Amey says even though it’s routinely booked, the center is simply too small, especially as event planners seek out more space post-COVID.

“The convention center is so tiny that you’d only really do one event at a time, maybe two,” Amey says. “A significant convention center can do two or three or four. We could have all the local events and also attract regional or even national or international events.”

A 2024 study by Chicago-based real estate advisory firm Hunden Partners suggests the same: the current center, even renovated or expanded, leaves too much on the table.

“This business is performing for you, but you are outmoded, outdated, and in a small building relative to who you are as a destination,” founder Rob Hunden, who has been advising on the convention center for 20 years, told the Durham City Council in September. “You’re so unique and authentic as a destination. The challenge is that it is physically hamstrung in the center of town in terms of what it can do to expand.”

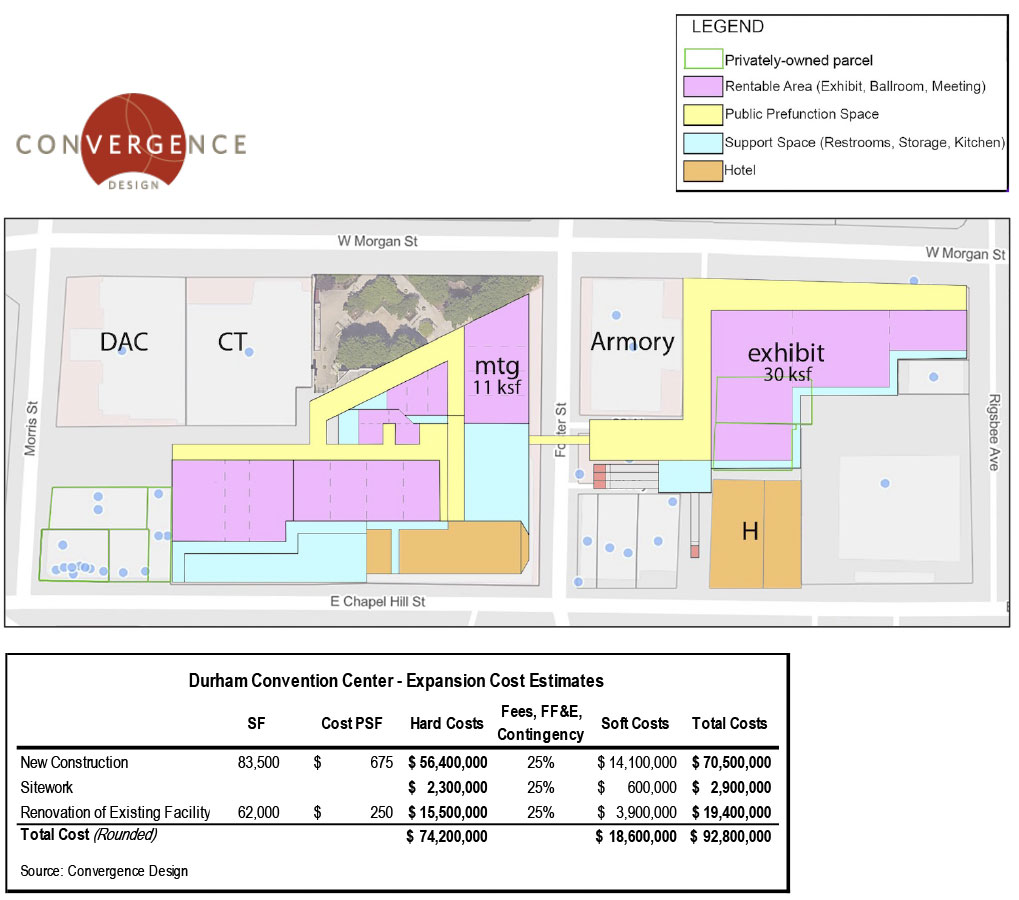

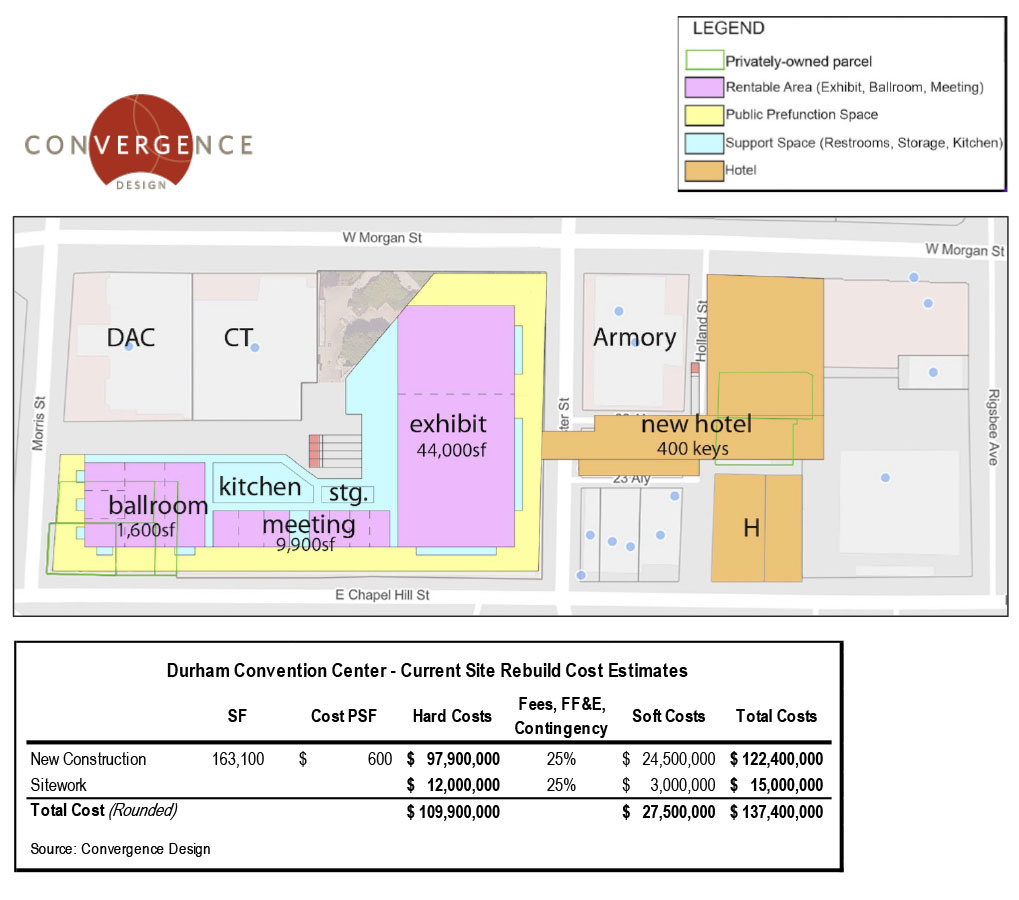

Hunden estimates that expanding the current convention center would cost about $93 million. This includes adding 11,000 square feet of meeting rooms and 30,000 square feet of exhibit space next to the Durham Armory across the street, which is also managed by the city. Even with the added 41,000 square feet of space, Hunden says the updated convention center wouldn’t be competitive in the region.

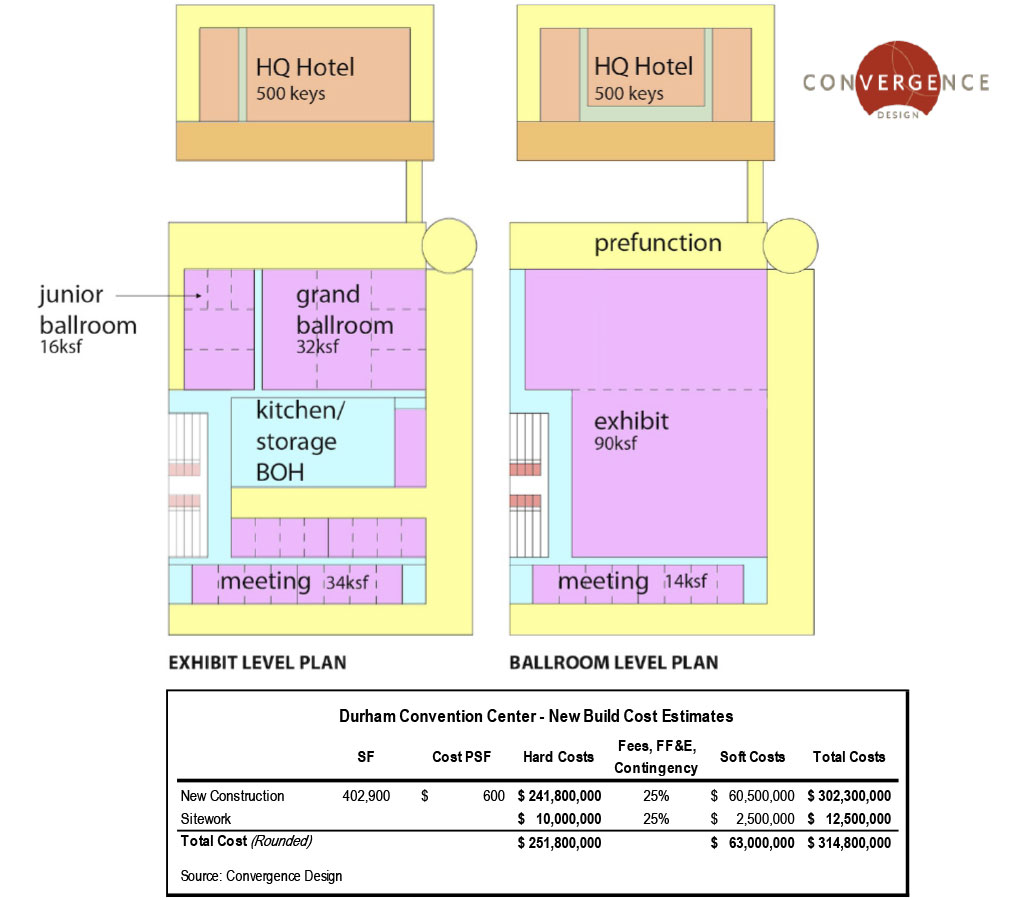

Instead, the firm recommends the city consider constructing a new, two-story convention center at an estimated cost of $315 million and an adjoining 500-room hotel at $225 million. That’s more than half a billion dollars in total construction cost, a staggering price tag. Those figures don’t include the cost of acquiring seven acres of land to house the new 403,000 square-foot complex, nor the additional reconstruction of roads and other infrastructure connected to the project.

But scared money don’t make money. For Williams and other leaders invested in the future viability of downtown, a new convention center is part of a larger vision for a more vibrant city center. Driving that vision is Discover Durham, the city’s tourism agency, and a new companion 501(c)3 called Durham Next. In 2024, Discover Durham unveiled its Destination Master Plan, a community-driven roadmap forecasting the infrastructure and amenities—like a revamped convention center—needed to keep Durham an attractive destination for visitors and residents over the next 20 years. Other ideas to come out of the initiative include a sportsplex and a freeway cap, which would create an urban park over NC-147.

“We can’t think small,” Williams says. “We can’t think, ‘oh, this is expensive so we have to do a convention center or something else.’ But instead, how can we build an innovation center that can host conventions and also weave itself into the fabric of our community?”

Traditional convention centers are not a lucrative business. According to The New York Times, big convention centers are a dying breed, and cities that spend money on them are erecting monuments to a bygone era, like if Rome built a new coliseum to host gladiator fights. Even Rob Hunden, the person who sold Durham city council on the concept for a shiny new center, told the Times just three months ago that “most of the 175 convention centers across the country operate at a loss.”

National trade shows that historically draw big audiences have seen attendance slide in the past few years. It’s difficult to know if this is the lingering effects of a global pandemic, or a new normal. Uncertainty about the future makes building a new convention center a hard sell to folks who see more immediate needs in the community.

“We can’t think small…How can we build an innovation center that can host conventions and also weave itself into the fabric of our community?”

Durham mayor leonardo williams

Shawn Stokes, owner of a number of downtown businesses including Luna, says that Durham is already missing basics like more efficient public transit, more sidewalks, public art and parks that would benefit residents, visitors and local businesses.

Stokes points to initiatives like the Raleigh Illuminate Art Walk or the new seven-acre Downtown Cary Park as accessible public amenities that draw a crowd without the proposed convention center’s $500 million-plus price tag.

“I know people in my friend group who are taking their kids to Cary to go check out the cool park that they just built there,” Stokes says. “How sad is it that families are leaving Durham to go to Cary to spend time in their public parks? Maybe after we’ve built a beautiful city that functions well for our own citizens, and it functions well for everyday tourists both regionally and nationally. Then it makes sense to build a convention center where the people that are coming to these conventions want to go explore the city.”

Stokes and others have also raised concerns that existing public works projects are sorely lagging behind. The Durham Rail Trail, a proposed 1.8 mile multi-use path connecting North Durham to Downtown, has been planned since the city bought the land in 2018. According to the city, it will be another year before construction begins. Stokes says projects like the Rail Trail give him little faith that the city can execute something like a convention center in time for current business owners to reap the benefits.

Not everyone on the city council is ready to rubber stamp a new convention center, either. After the Hunden presentation last year, freshman council member Chelsea Cook expressed concern over the center’s price tag, especially with large convention centers nearby.

“Land is extremely expensive, and it’s a very precious commodity in downtown Durham,” Cook told the INDY.

Convention centers may already be a saturated market just in North Carolina.

Raleigh is set to invest millions of dollars into renovating its own convention center, adding a whopping 500,000 square feet of additional space. Koury Convention Center in Greensboro offers 250,000 square feet, and Charlotte, the state’s largest city featuring two (lousy) professional sports teams, just opened a newly-renovated convention center in 2021 with 600,000 square feet of meeting space.

“We don’t need to be competitive in every single lane,” Cook says. “Convention centers struggle to make money, and that is why they are owned by cities and not by private developers.”

Williams and his allies believe a new Durham convention center could be a different story.

According to Hunden Partners, Durham’s current convention center is punching above its weight. Last year, unlike many peers, it did not operate at a loss: the center reported operating at a net gain, bringing in $4 million in revenue after losing money for several years. Hunden also says that $27 million in economic impact was lost over the last five years because of constraints to the current site, including meeting room size and date availability—suggesting a bigger, more modern convention center could thrive, despite trends in the industry.

But if local officials want an innovation center, they’ll have to come up with innovative ways to fund it that don’t overly burden Durham residents.

“We collect property tax, and we try to do every damn thing out of the property tax,” Williams says. “How do we get what we want without having to beat taxpayers over the head with this? So what I’m trying to do is be really creative in this approach. I’m trying to create something that’s going to pay for itself.”

Williams says corporate contributions are an option.

“There are organizations that are looking to make a name for themselves in our area,” Williams says. “…They ask us for something that’s going to make a significant, multi-generational impact. I can’t go to them with these small asks, but I can go to them and say, look, we have land, we have vision, we have a plan, and we have a space for you to put your name on this significant investment. I have to create those opportunities.”

In June, the state legislature, led by former state senator Mike Woodard, approved a new bill that changes how Durham allocates funds it collects when visitors pay taxes on hotel bookings. Starting this year, Discover Durham can spend hotel/motel occupancy tax funds on capital expenditures like a new convention center or sports complex—not just marketing.

While visitors and spending are up near pre-pandemic rates, according to Discover Durham (in 2023, 13 million visitors generated $80 million in sales tax revenue), costs for local residents and businesses are also up, and incoming sales and occupancy tax revenue is negligible compared to the half-billion dollars necessary for the new convention center.

“We don’t need to be competitive in every single lane. Convention centers struggle to make money, and that is why they are owned by cities and not by private developers.”

Durham City council member chelsea cook

But Williams and Discover Durham hope a new “innovation” center that goes beyond the conventional would lead to increased revenue and help offset costs— not only by attracting investors, but by bringing in more business for the center and drawing local residents, who would in turn support downtown businesses. Amenities could include a virtual reality space and other interactive studios akin to exhibits you might find at the Museum of Life and Science.

Durham can compete in a saturated market because of the unique flavor of downtown, argues Williams, who is acutely aware of the challenges businesses face as the owner— alongside his partner, Zweli— of two downtown restaurants. Most of Durham’s downtown businesses are locally-owned instead of chains, which Williams says distinguishes Durham from its competitors and keeps more of the money in the community.

“Imagine that the innovation center was to be able to host a four to five thousand person convention, but we go underground to build it, and above ground, it’s a beautiful open park and we put a Ferris wheel in downtown Durham and put an amphitheater out there where we can host concerts or speaking events on top of the innovation center. We’re just reimagining the use of our space,” Williams says.

The promise of economic windfall from a future convention center is enticing. Hunden partners projects that in a new convention center’s first 30 years, visitors would spend $5.1 billion at the center, adjoining hotel, and surrounding businesses, and the city would gain $101 million in tax revenue. But the common refrains from those skeptical of the project remain; could the money be more effectively deployed elsewhere, and will the convention center come online quickly enough to support businesses struggling now?

Billionaire sports team owners run the same playbook when trying to sell the public on supporting a new arena. They make the case that the tax break, or direct investment from the state and local governments, will pay dividends in new jobs and local business stimulation down the road. Williams is making a similar pitch to residents of Durham.

When asked about a new convention center, most folks on the street respond with a tepid shrug. Traditional convention centers like the one currently in downtown Durham aren’t the kind of place you happen upon on a stag night with the boys, or during a date with your partner.

“It is important what residents want to see in the future. But they’re not going to say a convention center, they’re just not. They’re going to say other things like family friendly activities and places to go, things to do,” Amey says. “…But every community is in competition with all other communities for resources and talent. The average person on the street doesn’t think about building capital improvement projects, but city leadership has to be thinking 10, 20, 30 years into the future about what’s going to get us to where we need to be.”

Is the convention center a necessary asset for Durham’s future, or a vanity project for a mayor looking to leave a lasting legacy during an election year? Are the two mutually exclusive?

“The average person on the street doesn’t think about building capital improvement projects, but city leadership has to be thinking 10, 20, 30 years into the future about what’s going to get us to where we need to be.”

discover durham ceo susan amey

Durham Performing Arts Center had its own complicated development process before opening in the fall of 2008. Local officials were unsure how to make the financing work and some residents preferred that the city invest in pressing needs like affordable housing. But former mayor Bill Bell and others persevered, Williams says, by taking a risk on their vision for what Durham could become. Now, DPAC is one of Durham’s biggest economic drivers, attracting international acclaim and hundreds of thousands to Durham annually.

Mayor Williams is optimistic that residents will eventually accept his vision for a multi-purpose innovation center that invigorates downtown in the way DPAC has for 15 years. He says he knows the project will outlast his time in local government, but that he hopes to leave a legacy that shows he “had vision and had courage to carry out the vision despite critique or commentary.”

Support independent local journalism. Join the INDY Press Club to help us keep fearless watchdog reporting and essential arts and culture coverage viable in the Triangle.

Follow Reporter Justin Laidlaw on X or send an email to [email protected]. Comment on this story at [email protected].