After seeing their former union dissolved by the state earlier this year, city employees in Titusville who work in the utilities and public works departments are organizing to form a new union with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 606.

Reorganizing their union would allow them to continue advocating for the workforce’s material needs — higher pay, better benefits and the like — collectively.

“It gives them a voice without the fear of retaliation,” said Todd Provost, a business manager for IBEW Local 606, a union based in Orlando that also represents nearly 2,000 blue-collar workers in the private sector, including electrical maintenance workers at Disney World. He’s been in talks with the workers in Titusville about forming a new, fighting union that would be affiliated with his local.

“Every person that works for a company deserves the right to have representation,” Provost told Orlando Weekly. “I don’t care if it’s a Disney cast member, if it’s a construction worker, if it’s a public employee. Everyone deserves the right to be represented by somebody to fight for them.”

To initiate the process of forming a union certifiable by the state, the workers filed a petition for a union election with the Public Employees Relations Commission, the state agency that oversees public sector labor relations.

Under state and federal law, at least 30 percent of workers in the proposed union (or bargaining unit) must sign cards in support of unionization and submit those cards with the petition in order to ask for a union election. Then, a simple majority of workers — 50 percent, plus one — must vote in favor of unionization in order for the union to prevail.

According to the petition, obtained by Orlando Weekly through a public records request, at least 91 out of 141 workers eligible for unionization in public works and utilities have already signed cards in support of unionization.

Although Florida is regularly disparaged as a “nonunion” state due to its low union membership rate — approximately 94 percent of workers don’t have union representation — Provost said it’s important for people to know that unions do exist in Florida and, yes, you can form your own, too.

While just 11 percent of U.S. workers, or 6 percent in Florida, are currently represented by a union, polling shows that a majority of Americans say they support unions. Unions also tend to be more common in the public sector, where total compensation is nearly 15 percent lower than for jobs held by private sector workers, on average.

As of October, the public works employees in Titusville have been working without a union contract and the protections previously guaranteed to them under it. “The city automatically, as soon as that [contract] was terminated, has started trying to change things that were in the [contract] to harm the employees,” Provost alleged.

One of the initial protections a union contract in Florida can offer workers is “just cause,” to help protect them from being fired for no reason. A union can also negotiate grievance procedures, to help protect against retaliation on the job, and workplace safety protections, in addition to higher pay and stronger benefits.

“They can’t fire me,” Provost quipped, candidly. “They have to deal with me. If we get a contract, I’m there to fight for the worker, and that’s what everyone deserves.”

“If we get a contract, I’m there to fight for the worker, and that’s what everyone deserves.”

Titusville city manager Thomas Abbate denied the allegations of retaliation and “harm” to employees, when reached for comment by Orlando Weekly. “Both myself as City Manager and the City are committed to providing the affected workers with employment opportunities that offer competitive wages, benefits and retirement provisions along with job security,” Abbate said over email.

“The city has no intention of changing the working conditions in the previous CBA [collective bargaining agreement] that harm our valued employees,” he added.

Provost, the union official, told our reporter last week that he hadn’t heard any response from the city about their new organizing drive, other than receiving notice that they appointed an attorney to represent the city as the process moves forward.

Abbate said, if workers do vote to form a union with the IBEW, he’s “confident” that the city would work with union representatives “in the same collaborative, productive manner as before” with the workers’ former union.

The fallout of Florida’s ‘union-busting’ law

It’s been decades since the public works employees in Titusville have had to go through the process of forming a union, and voting in favor or against doing so, in the first place.

And they’re not the only ones.

After the passage of an anti-union law (SB 256) in 2023, dozens of unions representing public sector employees across the state — employed by school districts, cities and counties — faced potential extinction.

The state law, backed by billionaire-funded anti-union groups, created a threshold requiring that at least 60 percent of workers voluntarily pay union dues (a small cut of a worker’s paycheck) in order to keep their union intact, while simultaneously making it less convenient to pay dues in the first place.

Under the Florida constitution, workers already can’t be forced to pay dues , so there’s less incentive for them to do so of their own volition. They can reap the benefits of having union representation, regardless of whether they support their union’s sustainability.

One of the unions caught in the crosshairs of that 2023 law — ultimately dissolved over the summer — was the union that formerly represented the public works employees in Titusville, a small city about an hour east of Orlando, located along the Indian River near Merritt Island. The workers were formerly represented by the Laborers International Union of North America Local 630, a union separate from IBEW, and had been for nearly half a century.

The workforce first voted to join LIUNA in 1976, according to state records. But only a small percentage of workers were voluntarily paying dues to the union as of April. The union, which also formerly represented workers in Rockledge, Melbourne and roughly a dozen other Florida municipalities, also didn’t have enough support from the workers in Titusville to keep it alive.

Under the new law, unions that have a dues-paying membership of less than 60 percent can petition the state for a recertification election. That’s if they can similarly get signed cards of support from at least 30 percent of workers. In this case, LIUNA didn’t feel confident they could get that showing of interest.

“[T]he Union acknowledged that it did not file a recertification petition, explaining that it did not have the required showing of interest statements necessary to support the petition,” a clerk employed by the Public Employees Relations Commission wrote in the union’s June 16 decertification order.

Ronnie Burris, business manager for LIUNA Local 630, described the aftermath of the new law last year in an interview with us as a “nightmare,” adding that the cost of compliance — for public employers, too — has been “enormous.”

“What it cost the taxpayers, what it cost the municipalities … none of that was figured,” Burris told Orlando Weekly last August. “All they wanted to do was get rid of, or try to get rid of as many unions as they could.”

Since the 2023 law took effect, more than 120 bargaining units across the state have been decertified, leaving more than 69,000 public employees without union representation or the protections previously guaranteed to them under a union contract.

Although teachers’ unions were the perceived target of the law, thousands of workers employed by the state, city and county governments (including in Orange County) have instead become collateral damage.

Mechanics and other blue-collar workers employed by the Greater Orlando Aviation Authority, overseeing Orlando International Airport, saw their union (also affiliated with LIUNA) decertified last June. A group of bus drivers, food service workers and other blue-collar workers for the Volusia County school district lost their union last spring, but later reorganized with the Volusia County teachers’ union.

Those workers officially voted to join Volusia United Educators this past October, after first petitioning the state 10 months prior, and were welcomed into the ranks with welcome arms. “Congratulations to the employees who are now eligible to once again have a contract and join their union,” VUE wrote in a Facebook post. “Welcome aboard to our new friends, we’ve been waiting a long time for this moment!”

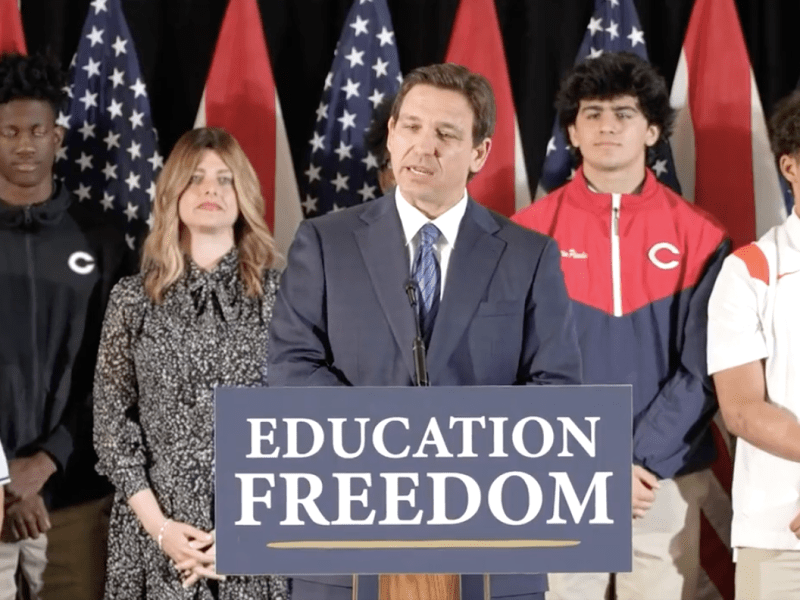

As of publication, not a single teachers union in Florida has been decertified since the law’s enactment, despite Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis’ best efforts. Instead, teachers and faculty have fought to organize their ranks well enough to keep their unions intact without facing dissolution by the state. So have other public employees determined to keep their unions and contractual protections alive.

Still, under the new law, they’ll have to do this annually, unless the law changes. “It was never about providing transparency for workers,” Rich Templin, a lobbyist for the Florida AFL-CIO, previously told Orlando Weekly in an interview about the 2023 law. “It was always about eliminating their ability and their constitutional right to collectively bargain.”

It’s unclear how long it will take for the state Public Employees Relations Commission to organize a union election for the Titusville employees. The Commission has been overburdened by its new workload under the new law, and has begged the state for additional funding in recent years to help keep it afloat.

If workers do end up voting in favor of joining his union, the next step would be to negotiate a union contract with the city management.

Subscribe to Orlando Weekly newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Bluesky | Or sign up for our RSS Feed

Related

Source link