Fallen leaves crunched underfoot as Bill McKibben strode up a hill and into the woods that surround his Ripton home. As his dogs galloped ahead through stands of birch, maple, beech and red pine, Vermont’s most famous environmental writer and activist guided a reporter on a well-trodden path that seemed to offer signs of the state’s changing climate around each bend.

We crossed a branch of the Middlebury River, reduced to a trickle by this summer’s record drought. We followed a trail that McKibben cross-country skis in winter — on the dwindling number of days when there’s snow. And we passed a road that still bears scars from the devastating flood of July 2023 that swept away several nearby homes.

“People tell themselves that Vermont is a refuge from the climate crisis,” he said. “There really is no such thing.”

McKibben is tall and lanky, with closely cropped gray hair and the jutting, angular features of a praying mantis. For more than three decades, the 64-year-old author, environmentalist and scholar-in-residence at Middlebury College has been the Paul Revere of the climate crisis, sounding the alarm not for invading British soldiers but for the Earth’s impending peril. The End of Nature, McKibben’s 1989 debut book and environmental call to arms, was the first to explain global warming to a general audience.

“When I started writing about it, all the scientific reports that people had done on climate change could sit on the top of my desk,” he said. “Now, they would fill an aircraft hangar.”

Since then, McKibben has written more than 20 books and countless essays and articles for such publications as the New Yorker, the Atlantic, Rolling Stone and the New York Times. The End of Nature has been translated into two dozen languages and is still taught in college classes. Professors have written research papers on his effectiveness as a journalist and organizer, and in 2014 a California biologist named a newly discovered gnat after him. (McKibben, a perennial gadfly, was delighted.) A winner of the Gandhi Peace Award in 2013, he’s the rare eco-warrior famous enough to get an audience with the pope and be interviewed by late-night TV hosts David Letterman, Bill Maher and Stephen Colbert.

Being the world’s most prolific author on global warming has brought McKibben no joy over the years, given how little humans have done to address it. Most of his Cassandra-like warnings — including of rising sea levels and increasingly intense heat waves and floods — came to pass as seriously as he predicted and often considerably worse. As he put it, “I would have given anything just to be wrong.”

But something remarkable changed in the past few years, and it wasn’t just the weather. In August, the country’s foremost climate doomsayer and self-described “professional bummer-outer” published a new book that offers something totally unexpected: a bright ray of hope.

Here Comes the Sun: A Last Chance for the Climate and a Fresh Chance for Civilization chronicles how renewable energy finally reached a tipping point in the past five years. Now, McKibben said, “It’s become cheaper to produce power from the sun and the wind than from setting stuff on fire.”

Solar has become the fastest-growing and most efficient means of powering the world’s economies, and the speed of its adoption worldwide is astounding even its staunchest proponents. No longer should we refer to it as “alternative” energy that, like Whole Foods Market, is healthy but pricey. Instead, he writes, renewables have become “the Costco of energy, inexpensive and available in bulk.”

McKibben doesn’t claim credit for sparking the solar revolution. But his journalism and grassroots organizing undoubtedly raised global awareness of the crisis and fueled a sense of urgency to address it. He is the rare writer who has successfully straddled the line between journalist and activist while remaining credible and respected.

“I’m sure he would be a happier person if he didn’t have to keep writing about this over and over again,” said author and journalist Sue Halpern, McKibben’s wife of 37 years. “When he started doing this work, no one else was doing it. Now, the New York Times has a climate desk, and there are hundreds and hundreds of environmental journalists.”

In the mid-2000s, while some were proclaiming the death of the U.S. environmental movement, McKibben and a group of Middlebury College students cofounded 350.org, the first, and now largest, global grassroots organization devoted exclusively to fighting climate change. Through 350.org, McKibben has helped organize climate demonstrations in every country on Earth but North Korea.

And he continues to bring new people into the fold. In 2021, he founded Third Act, a nonprofit group that harnesses the skills, experience and resources of people 60 and older to fight climate change and defend America’s faltering democracy — because, as he put it, “You can’t do climate work under authoritarianism.”

“Our species, at what feels like a very dark moment, can take a giant leap into the light. Of the sun.”

Bill McKibben

At a time when President Donald Trump continues to call climate change “a hoax” and advances a “Drill, baby, drill!” energy policy — for the first time ever, the U.S. didn’t attend the annual United Nations climate change summit, at which there was no agreement on phasing out fossil fuels — Here Comes the Sun has the potential to shift the narrative around renewable energy as profoundly as The End of Nature did for global warming. In recent months, McKibben has been barnstorming the country giving talks about the book, and he shows no sign of slowing down. Indeed, its uplifting message seems to have ignited in him a renewed energy and passion.

“[O]ur liberation and our destruction are arriving at precisely the same time, offering us a remarkable choice,” McKibben writes in the book’s introduction. “Our species, at what feels like a very dark moment, can take a giant leap into the light. Of the sun.”

The Solar Gospel

More than 80 people gathered in the Champlain Valley Unitarian Universalist Society in Middlebury on a recent weekday evening to hear McKibben talk about his new book. As he took the stage, the former Methodist Sunday school teacher apologized for not being at his best that night, as he had just spent 62 of the past 65 nights sleeping in hotel rooms on his book tour. Yet for the next 90 minutes, McKibben spoke eloquently and without notes, often drawing on his preternatural gift for quoting facts and figures from memory to maximum effect.

“Bill’s recitation of statistics of how much solar has been built will sometimes move people to tears,” said Jamie Henn, 41, McKibben’s longtime friend and 350.org cofounder. “People have no sense that we’re actually making progress.”

In fact, it was McKibben’s own astonishment at the rate of solar’s adoption that compelled him to write Here Comes the Sun late last year. As he told the Middlebury audience, the numbers are truly staggering: As of April, for the first time ever, fossil fuels were producing less than half of all electricity in the U.S. Thanks to renewables, California is now using 40 percent less natural gas to generate electricity than it did two years ago. When the sun goes down, the biggest sources of electricity for California’s energy grid are large solar- and wind-charged batteries that didn’t even exist three years ago.

And the U.S. is far from being the fastest adopter of solar, McKibben pointed out. Australia now produces so much energy from the sun that, beginning next year, the Australian government will give every citizen three hours of free electricity each afternoon, enabling them to schedule energy-sucking activities, such as drying clothes and charging electric cars, during those hours.

China is moving even faster. As of May, the Chinese were installing 3 gigawatts of solar panels per day — roughly the equivalent of building a large coal-fired power plant every eight hours. The result: In the past 18 months, China’s carbon dioxide emissions finally plateaued and have begun to decline, McKibben said, “which is the single best piece of good news I’ve heard in a long time.”

McKibben also noted that, notwithstanding Trump’s dismissiveness of renewable energy, the adoption of solar has finally leaped the political threshold. Recent polling data indicate that it’s hugely popular across ideological lines.

Utah became the first state in the country to legalize what’s known as balcony solar, which are photovoltaic panels that can be hung on porches and railings outside apartments and plugged directly into a wall outlet. (The Vermont legislature is expected to take up a similar bill in 2026.) In Europe, where balcony solar has exploded in popularity, thousands of apartment dwellers generate as much as a quarter of their electricity from it.

The biggest solar adopter in the U.S. isn’t California but Texas — not because of any concern over climate change, McKibben said, but because of its “sincere religious conviction” in the invisible hand of the free market. Simply put, solar is now cheaper and more reliable, especially in Southern states where the sun shines during much of the year.

“I know many people who have a Trump flag on their mailbox and solar panels on their roof, and it’s not because they’re worried about climate change,” McKibben said. “It’s because My home is my castle, and it’s a better castle if it has an independent power supply.”

Critics have largely praised Here Comes the Sun for its insights and hopeful message. Mark Hertsgaard at the Nation called it “an essential read for anyone who is interested in where the climate story is heading.” James Dinneen at New Scientist cheered it as “stirring” and “visionary.” And MSNBC’s Chris Hayes called it “arguably the biggest story happening in the world right now and also the most hopeful.”

The book’s few negative reviews have come primarily from the ideological right. Author, researcher and political strategist Ted Nordhaus panned it in a New Atlantis piece titled “How Bill McKibben Lost The Plot.” His biggest objection seemed to be that the Middlebury scholar is “quintessentially an unreliable narrator” because he wears multiple hats as journalist, activist, “movement prophet [and] ecovisionary.”

“I don’t think the New Yorker would be publishing Bill,” Halpern retorted, “if they thought that his whole point was to be more of an activist than a purveyor of important information.”

Close to Home

On the morning of our walk in the Ripton woods — McKibben’s preferred setting for conducting an interview — the New York Times had reported that the first six months of 2025 were the costliest in U.S. history in terms of climate-related natural disasters.

“That record will last until 2026,” he predicted. “Large sections of the nation’s second-largest city burned to the ground in January, and now it’s the 50th weirdest thing to happen in 2025.” Among the houses razed in this year’s California wildfires was McKibben’s childhood home in the hills of Altadena.

McKibben was born in Palo Alto, Calif., and grew up in Lexington, Mass., the last stop on Paul Revere’s midnight ride. There, he once held a summer job guiding tourists on the town’s historic green, site of the first skirmish of the Revolutionary War. When McKibben was about 10, his father, a journalist with Businessweek and later the Boston Globe, was arrested on the town green during an anti-Vietnam War protest led by a young John Kerry. By 13, McKibben was following in his father’s footsteps, writing for his local newspaper.

McKibben entered Harvard University in 1978, where he majored in government. The day the Harvard Crimson opened its doors to new students, McKibben was waiting on the steps outside the student daily to join the school newspaper’s staff. Throughout college he spent as many as 14 hours a day at the paper, eventually becoming editor of a staff that included now-famous journalists Nicholas Kristof and David Sanger.

A week after graduating from Harvard, McKibben went to work for the New Yorker, where he penned more than 400 byline-free articles for its “Talk of the Town” column. His first long piece for the magazine, published in March 1986, was titled “Apartment.” In it, McKibben traveled to the source of various objects in his modest New York City flat, including the electricity generated by a hydroelectric dam in Québec, oil drilled in Brazil and uranium mined in the Grand Canyon.

In those years, McKibben didn’t consider himself an environmentalist. David Brower, the Sierra Club’s first executive director, was a hero to McKibben’s father, an avid hiker, because he had saved the Grand Canyon from being flooded for a hydroelectric dam. But until McKibben reported “Apartment,” he had never given much thought to his own ecological footprint.

“This will sound funny, but it taught me that the world was a physical place,” McKibben said. Having grown up in the suburbs, where all of humanity’s systems are hidden from view, “Apartment” helped him see the fragile and interconnected nature of the environment and his place in it.

In the early 1980s, McKibben began researching another previously unnoticed phenomenon of American urban life: homelessness. As part of his reporting, he spent time living on the streets of New York City and ran a homeless shelter out of a church basement.

Through his work on homelessness, McKibben met his wife, Halpern, in 1986. She was teaching at Columbia University and raising money in her spare time to fund a summer camp for homeless kids. When William Shawn, the longtime New Yorker editor who had hired McKibben, was forced out of his job in 1987, McKibben quit the magazine in solidarity. The couple moved to the Adirondacks and married in 1988.

The End of Nature — and the Beginning

of Activism

With his environmental reporting still fresh in mind, McKibben began reading as much as he could of the emerging science of climate change. In June 1988, National Aeronautics and Space Administration scientist James Hansen testified before Congress that the planet had become measurably hotter than at any point in recorded history. The greenhouse effect was now detectable, Hansen told lawmakers, and computer simulations could predict, with “a high degree of confidence,” that it would trigger extreme weather events.

“I think it struck me much harder than it otherwise would have,” McKibben recalled. Until that point, environmental disasters mostly seemed like isolated shortcomings in human systems. When cities became choked with smog, auto manufacturers were forced to install catalytic converters, and the smog disappeared. When hydrofluorocarbons carved a hole in the ozone layer, those chemicals were eventually replaced.

But global warming operated on a far bigger scale. McKibben remembers thinking how extraordinarily difficult it would be to solve a problem whose cause — the burning of fossil fuels — undergirded the entire world’s economy.

The End of Nature, with its clear, accessible tone, colorful metaphors and morally persuasive arguments, had as profound an impact on the environmental movement as did Rachel Carson’s 1962 book, Silent Spring, which revealed the harm caused by the use of the pesticide DDT during World War II. With its jet-black cover and an illustration of the Earth on fire, The End of Nature captured the public’s attention and inspired a new generation of activists.

“The fossil fuel industry had so much money and so much power that losing the argument hardly mattered to them.”

Bill McKibben

Some of the book’s impact, McKibben suggested, was due to its fortuitous timing. Six months before the book’s release, the Exxon Valdez tanker ran aground, spilling millions of gallons of crude oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound, devastating wildlife and highlighting America’s dependency on fossil fuels. And a record-breaking heat wave that summer, covering two-thirds of the U.S., offered a stark preview of a much hotter planet.

“Like most writers and academics, I was a very firm believer in the power of argument,” McKibben said. Throughout the 1990s, he kept giving speeches and writing books and articles, he said, believing “somewhat naïvely” that winning the argument about the need to cut carbon emissions would be enough to move the needle.

“But the fight was actually not about data and reason and evidence,” he said. “The fight was about money and power. And the fossil fuel industry had so much money and so much power that losing the argument hardly mattered to them.”

McKibben realized that those who cared about climate change needed to assemble power of their own.

“Did I have any idea how to do that? Not really,” he said.

350’s a Crowd

A small auditorium in Middlebury College’s Franklin Environmental Center at Hillcrest was standing room only on a recent Thursday as students, faculty and alums crowded in for a colloquium on the state of climate education and activism in 2025. The discussion was part of a three-day campus event called “What Works Now?” celebrating the 20th anniversary of the Sunday Night Group, the weekly student meetups that led to the formation of 350.org. McKibben was clearly the star attraction, as students sat on the floor, leaned against windowsills and poked their heads through doorways just to listen.

“As you can see, anytime Bill speaks on campus, the crowds come out,” said Minna Brown, director of the Middlebury Climate Action Program.

During the discussion, McKibben urged the young people in the room not to minimize their role in the climate movement by calling themselves “student” activists. “You have as much right to a seat at the table as anyone,” he said.

“There’s no doubt that there are students who come here because of Bill.”

Jonathan Isham

McKibben didn’t call himself an activist when he first arrived at Middlebury in 2001 as a scholar-in-residence in environmental studies, a position later funded by a $1 million grant from the Schumann Center for Media and Democracy, largely at the urging of the late journalist Bill Moyers, McKibben’s longtime collaborator and friend.

“Bill decided he wanted to move from just writing about the challenge [of climate change] to acting to confront it,” Moyers told Imogen Rose-Smith for a 2014 story in Institutional Investor.

At Middlebury, McKibben reunited with fellow Harvard ’82 alum Jonathan Isham, now professor of economics and director of environmental studies. Even then, Isham recalled, McKibben was “a bit of a North Star” in pressing the issue of climate change. Since then, he said, McKibben’s impact on the college has been “profound.”

“There’s no doubt that there are students who come here because of Bill,” he said.

In January 2005, Isham taught a new class called “Building the New Climate Movement.” It was inspired by former governor Howard Dean’s presidential campaign the year before, with its meetups, blogs and decentralized leadership. Students researched grassroots movements, connected with community partners and organized a three-day conference at end of the winter term.

The conference got a write-up in the New York Times, in part, because two little-known environmentalists, Michael Shellenberger and Ted Nordhaus — the same Nordhaus who would later pan Here Comes the Sun — presented a 12,000-word thesis called “The Death of Environmentalism.” In it, they cited climate activists’ largely unsuccessful efforts to regulate industrial and automobile emissions. Environmentalists, Nordhaus told the conference, “have spent the last 25 or 30 years telling people what they cannot aspire to … That isn’t going to get you very far.”

The gauntlet had been thrown down. Beginning in late January 2005, a group of students in Isham’s class started meeting every Sunday night to organize climate action campaigns and demonstrations. (Twenty years later, the student group still meets on Sundays.) McKibben became the group’s informal adviser and source of inspiration.

“There’s no question that the Sunday Night Group put us in the center of the climate movement,” Isham said.

By 2006, the U.S. still had not ratified the Kyoto Protocol, a modest international pledge to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions to 5 percent below 1990 levels. Though McKibben wanted to do more to address the crisis, “There was no real climate movement to join,” he said.

So he started one. McKibben had recently returned from Bangladesh, where he had contracted dengue fever, a mosquito-borne disease that has become more common as the planet gets warmer and wetter. He made a full recovery but was struck by the injustice that thousands of Bangladeshis would not. People in that country, whose carbon emissions were so trivial as to be unmeasurable, were dying en masse from a disease that was being exacerbated by industrialized countries.

On Labor Day weekend 2006, McKibben and members of the Sunday Night Group organized a climate march, which loosely followed Route 7 north to Burlington. Seeking a poetic starting point, McKibben suggested that they begin at Robert Frost’s writing cabin in Ripton, a short walk from his own house.

“It was a really beautiful experience,” recalled Will Bates, 41, a 350.org cofounder and one of the original Sunday Night Group members, who made the five-day trek. Along the way, the marchers stopped at churches, museums and village greens; gave talks about climate change; listened to poetry and music; and camped overnight in yards and hayfields. Most days, they had 50 to 200 people joining them, with drivers honking and pedestrians waving in support.

By the time the pilgrimage reached Burlington, the march had grown to 1,000 people. When it arrived in Battery Park, the procession was met by every Vermont candidate for federal office, as there was an off-year election that November. All the candidates, regardless of party affiliation, signed a pledge to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent by 2050, which, at the time, was considered an ambitious goal.

When the Associated Press ran a story about it the following day, it described the 1,000-strong gathering as the largest demonstration against global warming ever held in the U.S.

“Good God! No wonder we’re not getting anywhere!” McKibben remembers thinking.

But as McKibben wrote in Seven Days on the 10th anniversary, the Vermont climate march “marked the end of my relatively quiet life as mostly a writer and the start of a hectic stint being mostly an activist.”

Stepping It Up

In 2007, several of the former Middlebury students involved in the Sunday Night Group moved to Burlington and started work on Step It Up, a campaign to organize similar climate actions around the country. Within months, they had 1,400 events scheduled in all 50 states. Their next goal was to take the movement global. Those efforts culminated in the formation of 350.org in 2008.

“It’s really a credit to Bill that he pushed us to think about doing something much larger than we ever would have thought possible,” said Henn, the 350.org cofounder who now runs Fossil Free Media, a climate-related campaign and communications firm.

Henn and others who’ve worked closely with McKibben over the years described his leadership style as visionary yet humble, a genius who is always willing to entertain other people’s ideas.

“One thing he’s never lost is an interesting combination of confidence but also humility,” Isham said. “He is a servant-leader second to none.”

As an organizer, McKibben would liken a demonstration to a church potluck, where everyone brings to the table whatever “dish,” or skills, they’re good at, be it writing, fundraising or website development. “It was all very Vermonty,” Bates said.

McKibben was the one who suggested the name 350.org. As he explained, Arabic numerals are universally recognized and require no translation. Also, the reference was instantly educational in that any mention of it in the press required an explanation: 350 parts per million represents what climate scientists consider the upper limit of atmospheric carbon dioxide for avoiding the worst impacts of climate change.

On October 24, 2009, 350.org held its first global day of action, two months ahead of an international climate summit in Copenhagen. In all, 5,200 rallies were held in 181 countries. CNN described it as “the most widespread day of political action in the planet’s history.”

McKibben remembers sitting in a borrowed office in lower Manhattan as photos of the rallies began streaming in online from every continent on Earth, sometimes at a rate of 30 per minute. Some of the “rallies” were tiny, including a sole Iraqi woman who held a sign at a military checkpoint, scuba divers underwater at a dying coral reef and climbers atop the highest peak in Antarctica. The images were immediately posted on the digital displays in Times Square.

Several of those photos now decorate McKibben’s living room. Aside from the birth of his daughter, Sophie, he said, “those were some of the most remarkable days of my life.”

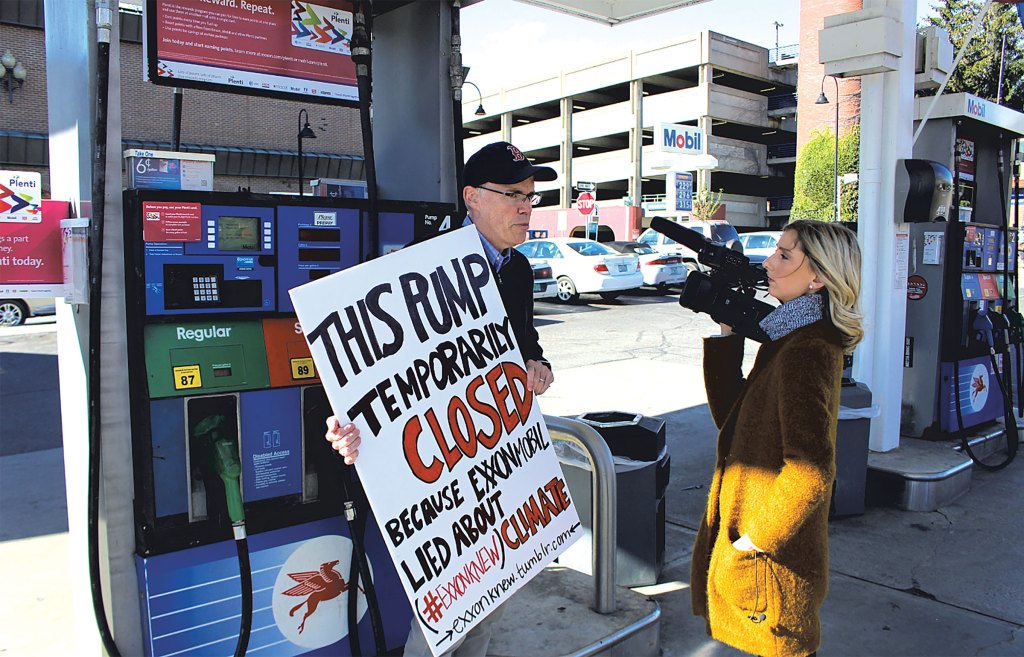

McKibben has never taken a paycheck for his work with 350.org or Third Act. And while his life definitely changed once he became an activist, it hasn’t always been for the better. In August 2016, he penned an op-ed in the New York Times about his “right-wing stalkers” — the Republican opposition research group America Rising Squared, members of which follow him around with cameras, trying to capture him in embarrassing moments.

The group has posted photos and videos online of McKibben getting off airplanes, riding in gasoline-powered cars and (gasp!) carrying plastic bags out of supermarkets on days when he had forgotten his reusable cloth ones. Someone even went through McKibben’s archive at Texas Tech University, where his papers are stored, digging up obscure quotes that were later posted out of context in an effort to discredit him or demonstrate hypocrisy.

McKibben has been unnerved and infuriated by these experiences, especially when his daughter reported that someone was taking photos of her, too. He even skipped a college mentor’s funeral so as not to cause a scene. But he considers such harassment the price he must pay for the cause.

“There’s comfort in the knowledge that the climate movement doesn’t depend on me,” he wrote in the op-ed. “For years now, I’ve been stepping back, mostly because I think the kind of movement we need is one that has thousands of leaders in thousands of places, connected like the solar panels on the roofs of an entire planet.”

A Book of Revelations

Ask McKibben whether he considers his career as an activist and journalist a success, and his answer reflects his signature humility, if not a touch of false modesty.

“I’ve written far more words about climate change than anybody else,” he said. “If that’s true, given the temperature of the Earth, then I’m the least successful writer that this planet has ever produced.”

Others beg to differ. Henn pointed to several successful environmental campaigns for which McKibben can claim credit. To date, the Keystone XL pipeline, which would move oil from the Alberta tar sands to Texas — and for which McKibben was arrested twice during protests — has yet to be built, in large part due to his writing and activism.

The carbon divestment movement that McKibben started made it harder for the fossil fuel industry, particularly coal companies, to raise financing for new infrastructure projects. (While few Americans have a coal mine or oil pipeline in their backyard, McKibben explained, most have some connection through their market investments, such as pensions and retirement funds.) And the significant incentives and investments in renewables contained in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, most gutted by the Trump administration, can be traced directly back to the efforts of 350.org.

“Given the temperature of the Earth, then I’m the least successful writer that this planet has ever produced.”

Bill McKibben

On a more fundamental level, Henn said, McKibben seems to have an innate sense for which way the wind is blowing, even when it’s not obvious to others. And right now, it’s blowing strongly toward solar.

As he stood at the podium at the Unitarian Universalist Society in Middlebury, McKibben, who is best buds with 22-year-old Swedish activist Greta Thunberg, observed aloud that most in the audience were old enough to qualify for Social Security.

“I’ve heard a few too many people my age say, “Oh, it’s up to the next generation to solve this problem,’” he said. McKibben considers that attitude both impractical and immoral. Not only are seniors the country’s fastest-growing demographic, young people also lack the wealth, structural power and freedom to make the necessary changes. After all, getting arrested at a climate protest does little to help a twentysomething get their first real job.

“If you’ve reached the point where you have hair coming out your ears,” McKibben added, “then you also have structural power coming out of your ears.”

McKibben’s newfound optimism — yes, he uses the “o” word now, albeit sparingly — isn’t some new organizing tactic or the product of him becoming a grandfather 19 months ago. Said Anna Goldstein, Third Act advisory board member and part-time consultant: “Bill is realistic and hopeful, and he sees how organizing moves the needle.”

McKibben always tempers his upbeat assessments with clear-eyed realism that humanity can no longer escape the most devastating impacts of a hotter planet but only mitigate their severity.

When Hurricane Melissa made landfall in Jamaica in late October, he said, a hurricane hunter aircraft clocked wind gusts of 252 miles per hour, the fastest cyclone speed ever recorded on Earth. That same day, in central Vietnam, the city of Hue was deluged with five feet of rain in 24 hours. And Vermont’s early arrival of winter, cheered by skiers such as himself: That, too, he said, was due to the North Pole being 35 to 40 degrees warmer than normal that week.

“Which is why it’s strange to find myself in some ways more cheerful than I have been about our prospects in a long time,” he proclaimed from the church lectern. “We have to take full advantage of the fact that the good Lord hung a large ball of burning gas 93 million miles up in the sky. And it would be a sin to waste it.”

The original print version of this article was headlined “Star Power | Ripton writer and activist Bill McKibben has surprisingly sunny news for our gloomy times: The solar age has dawned.”

This article appears in Nov 26 – Dec 2 2025.