Corn chowder. Cucumber salad. Mashed potatoes. As we sort through a large cardboard box of fresh produce, the woman beside me details all the ways she plans to transform these groceries into meals.

“I make a chicken soup, too,” she says, adding to the list, “and my grandson says, ‘It’s so good!’”

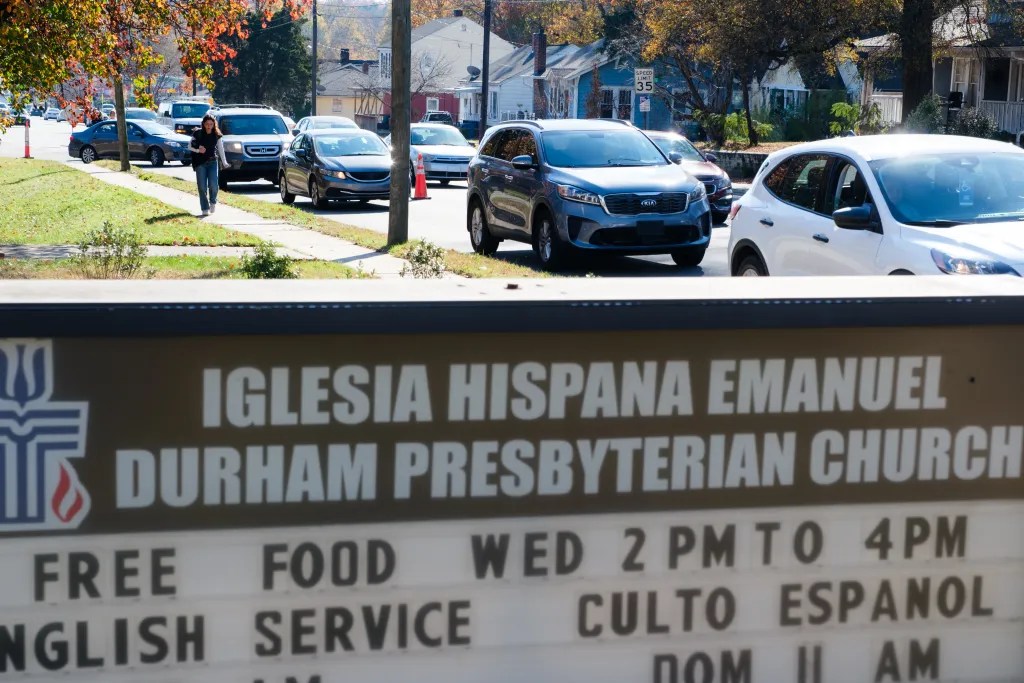

This woman, who shares her recipes but not her name, has eight grandchildren and not enough food, which is why she takes the bus every Wednesday to Durham’s Emanuel Food Pantry (EFP), a nonprofit that runs a weekly mobile food distribution service from the parking lot of Iglesia Presbiteriana Emanuel on Roxboro Street.

“If this wasn’t here, I would have to go home and find something to sell, go to the pawn shop to get food,” she says. When I ask if the 16-ounce container of milk she received is enough for both the chowder and the potatoes, she says, “I make it work.”

This sentiment, like the woman’s careful process of food inventory and transport, is a microcosm of the activities all around us in the busy parking lot.

Today, in the span of just two hours, more than 650 cars will cycle through, moving through a team of volunteers who direct traffic, scan tickets, pop trunks, and load in produce boxes and large bags of shelf-stable pantry items. (If there are kids in the car, volunteers offer one of a limited number of desserts.) When supplies run low, volunteers driving pallet lifters bring more boxes and bags. The efficiency of motion feels factory-esque, but the atmosphere is warm and fun—music plays, and greetings are exchanged in English and Spanish.

Along with the drive-in service, another 100 or so clients pick up their food from the pantry’s walk-up line, which, like the car service, requires nothing more than signing up online for a spot. There are also delivery options for home-bound clients and a special pickup time for church members. Joy Newburn, EFP’s part-time operations manager, is handing out flyers with instructions for how to sign up for next week’s service—that is, when she’s not directing traffic, managing volunteers in fluorescent vests, or doing a hundred million other things.

Newburn is one of only two EFP employees, both of whom started just this year—even though the pantry is going on its sixth year of service. In five years, the initiative has grown from a handful of folks serving 30 families a weekly hot meal in the church basement, to this—Durham County’s largest emergency food assistance program, with more than 150 volunteers a week that serve 860 families.

Newburn says that when she came on board, the pantry’s distribution setup was already a well-oiled machine, but she still felt like she was “drinking from a fire hose.” Today, her buoyancy is evident and contagious. Or maybe the cheerful optimism and make-it-work determinism I see all around is just the ethos necessary to make an all-volunteer effort work so well and for so long.

Back at the walk-up table, Bruce, a disabled veteran who rides over in his scooter from a nearby group home, is cracking jokes with two longtime volunteers and picking up his goods. “I get ’em talking,” he says of the volunteers. He tells me he makes too much to qualify for the government’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) but not enough to cover his grocery bill. “A lot of veterans don’t get enough,” he says, which is why he drives his “Rolly Royce” here every week.

Of course, even if Bruce did qualify for SNAP, it wouldn’t necessarily make a difference. October’s government shutdown put an abrupt stop to SNAP benefit distribution, which put the 1.4 million low-income North Carolina residents who rely on the program to feed their families at an even greater risk. Those delayed benefits are now slowly beginning to return, but for many recipients, SNAP wasn’t enough in the first place to keep healthy food on the table through the end of the month.

Plus, SNAP faces permanent cuts as Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act becomes law; enacting its provisions will push millions of Americans off the nation’s largest antihunger program. If folks were still hungry with SNAP benefits, the pains of the shutdown’s temporary suspension are only a preview of a much worse disaster to come.

Though the steady stream of cars stretches around the block and backs up into the neighborhood, where volunteers are positioned to help traffic flow as smoothly as possible, few neighbors complain about the congestion. Maybe because seeing all the vehicles lined up makes it apparent how widespread food insecurity is and gives close proximity to a problem that, for how big it is, remains mostly unseen.

Food insecurity is largely invisible—you can’t always see hunger, but you certainly can see its effects in chronic diseases, poor health, and children who are struggling in school due to developmental differences. Historically, North Carolina has had one of the highest rates of food insecurity in the United States, and according to 2023 data from Feeding America, in Durham County 13.8 percent of residents cannot access enough food.

“Once you know that almost 50,000 people are food insecure in this community that has so much brain power and so much wealth, you cannot turn a blind eye—it’s almost inconceivable that this was such a hidden issue for so long,” says Miguel Rubiera, who, along with his wife Margaret, founded the Emanual Food Pantry in 2020.

After careers running other nonprofits (including Durham’s Habitat for Humanity), the Rubieras’ “retirement” has been spent building both the food pantry and a related tutoring program, which is also held on church grounds. Knowing the Rubieras’ skills as passionate advocates and leaders, Pastor Julio Ramírez-Eve initially asked for their help in turning the church’s Wednesday night dinners into a mobile food pantry during the pandemic. Seeing the growing need during lockdown, the couple worked to source food, raise funds, and recruit help—growing the organization organically and welcoming volunteers and their input every step of the way.

“Once you know that almost 50,000 people are food insecure in this community that has so much brain power and so much wealth, you cannot turn a blind eye—it’s almost inconceivable that this was such a hidden issue for so long.”

Miguel Rubiera, cofounder of emanuel food pantry

“We did not sit down in the spring of 2020 and say ‘OK, we’re going to get this food pantry going and this is our strategic plan,’” says Margaret Rubiera in a Zoom interview. “It was all just responding to the needs of the moment and continuing constantly just to respond …. It’s only been recently that we’ve been able to sit down and really strategize for the future.”

That future includes an advisory board, which transitioned into a board of trustees in 2023, the year the pantry became its own nonprofit organization, separate from the church that houses it. As the pantry has grown, its real estate needs have expanded as well—growth that the church has been able to accommodate so far, though it does seem that the operation is pulling at the modest building’s seams.

The organization’s biggest expansion is the appointment of a new executive director, Pam Ryan, who has been on the job for only a few weeks. With an extensive background in the antihunger field, she’s excited to be leading such a vital organization. “The volunteers are rivaled by none—they clamor for those volunteer spots!” she says.

Ryan’s arrival will allow the Rubieras to step back from day-to-day operations, but they are hardly abandoning the cause—instead, the couple plans to move into a larger advocacy role, working with 15 other area food pantries as a coalition with the hopes of changing perceptions around antihunger work. “Everybody who has been born is entitled to food and shelter—that’s social justice, not charity,” says Miguel.

He is especially excited to develop private-public partnerships to help alleviate food insecurity.

“We have so many businesses in our community talking about food as health, food as ceremony, but they don’t do baloney …. They talk a lot. They have conferences, they write articles, but they don’t do anything about it,” Miguel says. “With the coalition of pantries, we are going to go to people and say, ‘OK, put the money where your mouth is.’”

During this moment of transition and growth for the Emanual Food Pantry, all signs nationally and locally show that the need for food assistance programs is only going to increase, and the government shutdown SNAP debacle is just one of the many reasons pantries like EFP are under pressure. People didn’t have enough to eat before the federal cuts to food banks and SNAP benefits, so donations from private entities and individuals are essential to cover the gaps.

“The reality is none of us had any fraction of an idea that it would be this big or around for this long—it’s just been about kind of holding on for dear life to do whatever we can to meet this growing demand,” says Jacob Boehm, who serves as chair of EFP’s advisory board.

Boehm, a local chef whose company Snap Pea creates pop-up dinners around the Triangle, first started volunteering at the pantry five years ago.

“I kept hearing rumblings of this food pantry on Roxboro that was ‘no questions asked’ and had really good food—it stood out as a magical unicorn of food assistance programs,” Boehm says.

I kept hearing rumblings of this food pantry on Roxboro that was ‘no questions asked’ and had really good food—it stood out as a magical unicorn of food assistance programs.”

jacob boehm, emanuel

food pantry board member

“No barriers, no questions asked, so anyone can come, and then a prioritization of high-quality, fresh produce,” he continues. Situations where organizations have to make do without such produce, he says, make jobs “ten times harder because you have to worry about cold chain storage and spoilage.”

When I compliment the produce boxes in front of us, saying they look like the sort of thing you’d get from a CSA box, he says, “You’d be lucky to get a box like that at your CSA.”

Boehm’s pride in what EFP gives away is well deserved. The controlled chaos of Wednesday’s distribution is only possible because of another well-practiced process, one with even more moving parts: food donations. Along with donations from the Food Bank of Central and Eastern North Carolina, the Inter-Faith Food Shuttle, Farmer Foodshare, and food recovery programs from stores such as Costco, Wegmans, and Whole Foods, EFP accepts all kinds of smaller donations as well.

Tuesdays are when the big trucks come in, and the major donations are unloaded—once again, trained volunteers use pallet jacks and organize stacks of produce, pantry items, and bread in Tetris-like configurations. It’s like Christmas morning and moving day merged—stuff all around and boxes full of surprises, but once again, there’s far more method than madness. Volunteers know their roles and jobs and do them to rocking music: organizing items, building and breaking down boxes, and filling up bags with rice, beans, pasta, and dry goods.

Produce box assembly is where the real action is. First, the produce gets sorted. The recovered items that aren’t fresh enough to be included are composted or cooked for a volunteer meal. There is no food waste—farmers come pick up the compost. Then the numbers are tallied: How many ears of corn in each box? One or two cabbages? Volunteers pick a vegetable and then hit repeat, filling box after box.

All of this happens under the watchful eye of Newburn, who keeps inventory of the donations via a program on her phone and can gauge from experience where the gaps are. If she sees something important missing—say, tomatoes—she can supplement, thanks to cash donations, and place an order with a local merchant. She has a standing order with El Camino, a Mexican food distributor just minutes away, to buy bananas. All the foods she uses to supplement donations need to be healthy, fresh, and attuned to a culturally diverse audience.

There’s a real waste-not, want-not mentality to all operations, which makes sense given that this is a group of people who know the value of a good meal and the level of scarcity around. Plus, intentionality abounds in little decisions that support the organization’s core mission. Instead of ordering pizza to feed the volunteers, who are often working through their lunch hours, the board decided to hire a member of the church to prepare meals on-site, made from recovered food that couldn’t go into the boxes.

The practice isn’t just a smart way to use food that’s too fragile or wilted for distribution; it’s a way to break bread together that embodies the spirit of community. The people working here share the same food as the clients who use the service.

“One thing I have absolutely loved has been seeing how, in these two-hour volunteer shifts, people have come together and gotten to know one another, free from the artificial barriers that we normally set up,” Margaret Rubiera says, and I agree. I felt that erosion of boundaries at EFP, about how exchanging food—and recipes—creates connections, no matter where you fall economically.

By the end of the day, the wall of refrigerators I watched fill up just a day before are now bare—as are the shelves and tables where the produce boxes and pantry bags were made and stored. Ditto in the parking lot—the pallets full of food are almost gone, but the line of cars continues. There used to be leftover boxes and bags that would be shared with other nearby food pantries. These days, there are no leftovers.

It’s a week later, and the circumstances are different: the arrival of federal Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents in Durham—spotted yesterday less than a mile from the church—has raised concerns around today’s food distribution. Many area businesses that cater to a Latinx clientele are closed.

The leadership of EFP, meanwhile, has been hard at work trying to figure out how to keep its neighborhood safe. The beautiful boxes of produce are ready, the staples bagged. Plus, members of the Triangle Association of Muslim American Mothers plan to distribute halal chickens at today’s pickup, as they do every year for Thanksgiving.

The threat of ICE activity in the area is a new constraint—yet EFP does what it has years of experience doing: responding to the needs of the moment. Calls are made, and processes are changed on the fly. Siembra NC, an immigration advocacy group, is on hand to help, as are more volunteers. Pastor Ramírez-Eve, who for 20 years has led the church that houses the EFP, offers a long view of what is happening today, telling me how the food pantry at its very beginnings, before it became its own entity, began in difficult times—the economic uncertainty at the end of the Bush administration.

“Right now we have another crisis affecting our community, and we try to deal with that,” Ramírez-Eve says of today’s upheaval. “The idea is to be present for the community, to provide space and support—especially for people who have a lot of need. That’s the way, that’s the mission we have.”

Around us, service has started—cars are pulling in, and along with a produce box and a pantry bag, volunteers are loading halal chickens and eggs into trunks or, at the walk-up stand, placing them carefully into shopping carts.

“The good thing is the community is coming. People in the [surrounding] neighborhoods are coming and asking how they can be helpful,” Ramírez-Eve continues. “That’s beautiful in this particular moment. I think it’s a blessing to see how many people are coming here to be a good helper. We are in unity with the Durham community.”

To comment on this story, email [email protected].