The disbanding of a civic organization may not seem cause for celebration. But optimism and an air of a job well done prevailed in September, when a business-casual crowd gathered in Burlington to bid farewell to Let’s Grow Kids.

A decade earlier, the nonprofit had launched a campaign to create affordable, high-quality childcare in Vermont. It was a lofty goal for a system that felt almost irreparably broken. At the time, discouraged families faced long wait lists for childcare slots and, if they got one, struggled to pay exorbitant tuition. Childcare providers were limping along on razor-thin profit margins, and early childhood educators working for them earned far too little to support themselves. On top of all that, there existed no good model at the national or state levels for how to meaningfully address the worsening crisis.

Let’s Grow Kids, a broad and well-funded coalition representing childcare providers, parents, business leaders and the politically connected, became the homegrown vessel for reform. The group gave itself 10 years — a term that ended this fall — to rally Vermonters to push for major public investment in childcare that would begin to answer the state’s gaping needs.

The increased funding has helped create more than 1,700 new childcare slots.

That investment would ultimately take shape as Act 76, a sweeping law passed in 2023 that directed $125 million annually, largely through a payroll tax, to expand subsidies for families and funds for childcare providers. In the two years since the bill’s passage, Let’s Grow Kids focused on monitoring the law’s rollout and making sure that other organizations were poised to take over the mission to fix early childhood education.

At a time when the cost of living has achieved remarkable political potency, Act 76 has made sizable strides in expanding the availability of affordable childcare in Vermont. The increased funding has helped create more than 1,700 new childcare slots, according to state data, and the ranks of children enrolled in the state’s financial-assistance program for childcare have swelled by more than 4,000. Last year, more early childhood programs opened than closed — a first since officials started keeping track.

Although much evidence remains anecdotal, some middle-income families report feeling a lighter financial burden, childcare providers say they have been able to expand their programs and pay their workers better, and certain businesses report that their employees have had an easier time finding childcare as provisions of the law have been rolled out.

“Every step of the way, we were like, ‘Is this real?’” said Kristen Dunne, executive director of Mary Johnson Children’s Center in Middlebury. With the increased funding, she said, “we’ve been able to dream rather than just survive.”

Let’s Grow Kids’ longtime CEO Aly Richards told the crowd gathered for the farewell, which included Democratic Senate President Pro Tempore Phil Baruth and Republican Lt. Gov. John Rodgers, that her organization was now ready to “pass the baton.” The splashy event at the Hula coworking and event space — replete on this day with charcuterie and crab cakes, flower-themed Lego centerpieces, and the obligatory Ben & Jerry’s treats — reflected the well-appointed professionalism of the Let’s Grow Kids campaign, which at its height boasted 35 staff members and raised $77 million, much of which went to stabilize existing childcare programs. It was also an opportunity for Let’s Grow Kids to tout its success: During a panel discussion, policy experts hailed Vermont as a national model for investment in childcare.

Still, no one was bold enough to declare “mission accomplished.” Childcare workers still lack the recognition, salaries and benefits they deserve, Richards said in a subsequent interview. A bill to make early childhood education a regulated profession, like nursing, was introduced during the last legislative session and could face resistance when it is taken up again in the new year.

Despite the program’s promising early gains, shortcomings remain: a continued dearth of spots for infants, persistent childcare deserts in rural areas and a subsidy program that hasn’t captured every family who is eligible. There still isn’t complete buy-in from the business community, one of the key groups that helped pass Act 76.

Yet Let’s Grow Kids had laid a sound foundation on which further improvements could be built, Richards said. The organization has spun off a lobbying arm, with a staff of three, that will continue to work at the Statehouse. And First Children’s Finance, a national nonprofit and lending institution, set up shop in Vermont in 2023 to provide grants and technical assistance to childcare businesses.

“We needed Let’s Grow Kids to put childcare on the map and to get a sustainable funding source,” Richards said. “And the movement will live on because of that work.”

‘A Huge Difference’

For Alison Byrnes and her husband, the availability of cheaper, high-quality childcare was the encouragement they needed to expand their family.

Three years ago, paying for two children to attend Montpelier’s Turtle Island Children’s Center was a struggle for the couple, both public school teachers. At the time, they were spending about $29,000 annually on tuition. Byrnes had to rely on her mother to pay for it.

“Everything about being a parent of young children in this state is so challenging,” Byrnes told Seven Days at the time. “People are choosing not to have kids because we have no support.”

“There’s no way we could have afforded a third child without the subsidy.”

Alison Byrnes

But the passage of Act 76 changed the picture. Under the law, families making as much as $248,000 annually now qualify for some financial assistance, depending on how many children they have. That makes Vermont the state with the highest income eligibility for childcare assistance. Byrnes had a third child in 2024, months before that increased subsidy threshold took effect. Though her oldest child is now in elementary school, her two younger ones attend Turtle Island full time. The new subsidy, on top of separate pre-K assistance for the middle child, now saves Byrnes more than $1,100 a month, bringing her annual bill to less than $12,000.

“There’s no way we could have afforded a third child without the subsidy,” Byrnes said. The expanded eligibility has “made a huge difference for so many families.”

Data suggest that Byrnes is right. In the two years after September 2023, 4,355 additional children were enrolled in the expanded childcare financial assistance program, with an 82 percent jump in infant enrollment. A two-parent, two-child Vermont household earning enough to maintain a modest standard of living can now save between $7,400 and $23,000 a year using the subsidy, depending on where they live. Nonetheless, advocates believe that hundreds, or even thousands, more families are eligible to take advantage of the expanded program but may be unaware.

“We still have a lot of families who just truly have no idea what the subsidy is, who would apply, where they would apply,” said Jocelyn York, executive director of Turtle Island. York herself does provide that information when families enroll.

The state has worked to spread the word, according to Janet McLaughlin, deputy commissioner of the Child Development Division at Vermont’s Department for Children and Families. It collaborated with a marketing agency to create digital ads, social media posts and radio spots. And it sends posters and brochures about the program to doctors’ offices, libraries and other social service agencies. The state also contracts with 12 organizations, mostly parent-child centers, across Vermont that help people sign up.

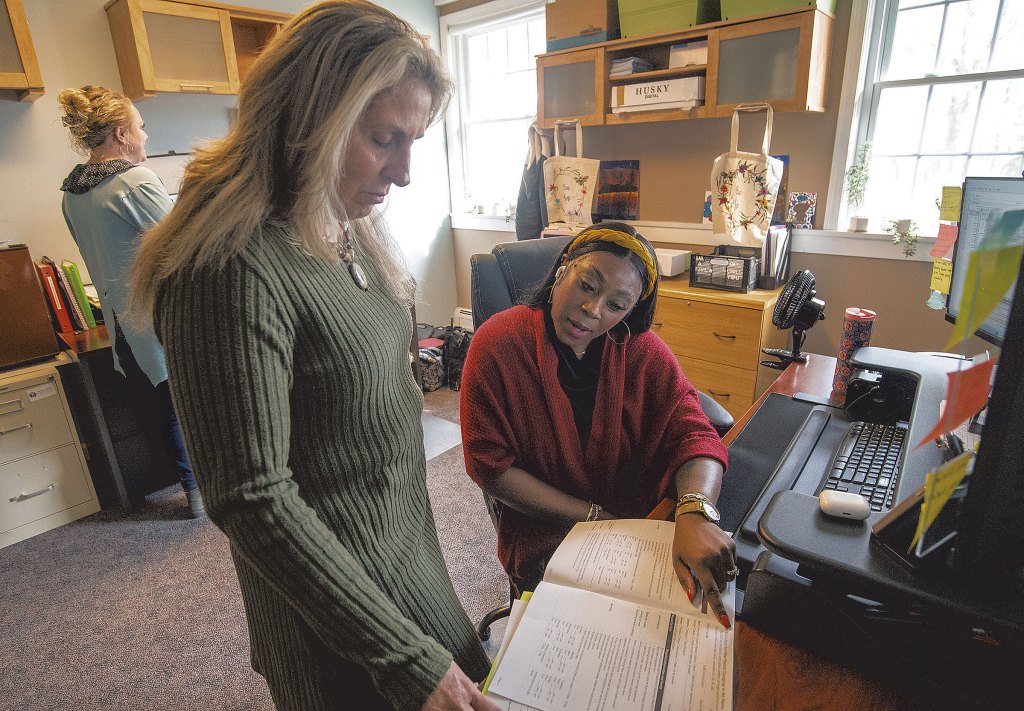

At one such center, the Family Place in Norwich, Chastity Macie assists low- and middle-income parents with applications. Beneficiaries have been able to use their savings for other necessities, such as housing, clothing and food.

Macie said she’s heard of families just across the river in New Hampshire who moved to Vermont to take advantage of the expanded childcare opportunities.

“We are working with so many families who previously applied but didn’t qualify,” Macie said.

Families seeking subsidies are required to provide extensive documentation, which can prove a barrier for those with nontraditional work or family arrangements.

Bethan Rowlands, whose income as an occupational therapist varies widely from month to month, said she and her husband weren’t able to get a tuition discount after she declared income from a particularly busy working period, alongside his fixed annual salary. The Addison County couple were told they’d have to reapply for the subsidy every time their income changed, which felt too onerous to pursue.

Kelly, a single mom in Winooski who asked that her last name not be used because of her family situation, said she was initially denied a childcare subsidy for her three children because she hadn’t yet divorced an abusive husband, whom she had left years before. Eventually, she worked with Child Care Resource, an organization in Chittenden County that contracts with the state, to receive a separate “family support” subsidy to cover care for a year.

Macie, the Family Place employee, said that amid the current housing crisis, some parents who have separated continue living together to avoid multiple rents. That can complicate their ability to prove eligibility.

But while the subsidy expansion has created some bureaucratic hurdles, Sara Cicio, a Barre resident, said she was pleasantly surprised by the state’s responsiveness. As a federal employee, she was working unpaid during the government shutdown. During normal times, she and her husband, an HVAC technician, qualified for childcare financial assistance that left them with a “family share,” or copay, of $275 a week. With help from the Family Center, she submitted a new application reflecting her loss of income. In about two days, Cicio said, the state temporarily slashed her copay to $75 a week.

Provider Payoff

Sunlight pours through large windows into the Growing Tree childcare center in the town of Addison, throwing a cheerful glow over picture books, wooden blocks and play areas. Outside, children frolic on swings and new play equipment against a picturesque backdrop of farm fields and mountains.

The animated scene is a stark contrast from just a few months ago. The sun-splashed building once housed the town’s elementary school, which closed in 2020 and sat empty, a depressing emblem of the aging state’s population trend lines. But in August, center director Michelle Bishop brought the building back to life with the Growing Tree, which now serves 16 high-spirited toddlers and preschoolers.

Bishop’s program is one of more than 100 childcare programs that have opened since Act 76 went into effect two years ago, creating around 1,700 spaces for children and 400 jobs for early childhood educators. Dozens more centers have been able to expand with the help of state-funded grants.

Access to funds enabled by Act 76 made opening her center possible, Bishop said: “I will be forever grateful.”

Before she did it, though, she crunched the numbers with the help of First Children’s Finance, the national nonprofit that set up shop in Vermont using state money. The organization helped her develop a business plan and navigate licensing regulations. Through First Children’s and a separate organization, Building Bright Futures, Bishop was awarded more than $100,000 in grants — money she used for furniture, educational toys, art supplies and playground equipment, as well as for insurance and hiring staff.

Eighty percent of Bishop’s families, most of whom live in the small town of Addison, qualify for full or partial childcare subsidies. The help has allowed Bishop to pay her three full-time teachers between $18 and $24 an hour, depending on their education and experience. She’s also adding a new classroom that will provide spots for 10 more children.

Wendy Chase and Jackie Prime, teachers at Middlebury’s Mary Johnson, said Vermont’s increased investment in the childcare system encouraged them to go back to school to get college degrees through a publicly funded program that provides tuition support. Both now make more money because they are on a higher rung of the childcare center’s pay scale.

Home-based programs have also benefited from the state largesse. Taylor Brink runs one out of her St. Johnsbury home, where children spend most of the day exploring the outdoors. She enrolls 12 children, most of whose families qualify for financial assistance. The state money allowed her to hire a full-time infant teacher and a part-time teacher, she said. Two grants have helped her renovate her home to comply with safety regulations, boost staff pay and purchase outdoor equipment.

In Barre Town, all but one of the families who send their children to Alexandria Whitcomb’s home-based program qualify for financial assistance. One mom with a child at the program was able to quit a second job that she’d taken solely to pay for childcare. Whitcomb, meanwhile, has used the additional funds to purchase higher-quality art supplies and hire teachers to come in for weekly art, yoga and music lessons.

Systemic issues persist, though. While a majority of centers have been able to pay teachers a higher salary, many haven’t been able to offer health insurance, the costs of which have skyrocketed in recent years. And there remains a dearth of spots for infants, who require the most intensive supervision.

Nearly four in five Vermont childcare owners and directors reported increased wages in the previous year, according to a 2024 survey, but some still have trouble hiring because they are unable to offer health care benefits.

“Health insurance is a huge gap and more of a reason than pay that people don’t take jobs,” said Phoenix Crockett, who co-owns Crockett Academy for Early Liberal Arts, a Williston program for infants, toddlers and preschoolers that opened in May.

Crockett said he would offer a health plan for his employees if he could find one that was reasonably priced. But when he reached out to MVP Health Care to inquire, he learned that doing so would run him an additional $800 a month per employee, which he said wasn’t financially feasible.

In addition, centers that offer infant care find the finances more challenging than those catering to older children, in large part because of more rigorous staffing mandates. State rules limiting enrollment to no more than four babies per teacher mean that running an infant room doesn’t always pencil out, even with the increased subsidy reimbursement rate. Crockett said he offers infant care because he sees the yawning need: Crockett Academy’s eight slots were quickly filled, so he added four more, but the center still has a wait list of more than 70 families.

His infant program is “not even close” to meeting the community demand, Crockett said.

Sonja Raymond has run into technical difficulties and laborious data entry requirements while trying to manage the subsidies for her Apple Tree Learning Centers in Stowe and Morrisville, which together serve close to 200 children. She’s also worried about a new provision in the law that caps how much tuition can be raised in a given year, based on inflation. That limit could jeopardize her ability to pay employees a competitive wage, she said.

Yet overall, Raymond said money from Act 76 has enabled her to renovate rooms and increase the number of kids served by the centers. She said she has attended childcare conferences and described the positive impacts of the new subsidies to providers from elsewhere.

“People are pretty flabbergasted about what’s happening in Vermont,” she said. “It’s just not like this in other states.”

A Campaign with Capital

The man behind Let’s Grow Kids is an 80-year-old real estate developer and philanthropist from Stowe. Rick Davis was drawn to the childcare cause decades ago during an encounter at one of his construction sites. A group of kids had stolen some tools, and, rather than pressing charges, he asked to meet with them and their parents.

“They had the cards stacked against them simply due to the circumstances in which they were born,” Davis wrote in an email. “The unfairness of it struck me; also the cost to the State of Vermont by not addressing it.”

That prompted Davis, along with private-equity investor Carl Ferenbach, to found the Permanent Fund for Vermont’s Children, which bankrolled a range of initiatives, from early intervention services for babies and toddlers to youth mentoring. The organization was instrumental in the passage of a 2014 law that provides all 3- and 4-year-olds in Vermont with 10 hours a week of free preschool.

Around that time, Davis decided to narrow the organization’s scope to ensuring that all Vermont children had access to high-quality childcare. That campaign became known as Let’s Grow Kids.

Davis recruited Aly Richards, who was then-governor Peter Shumlin’s deputy chief of staff, to lead the effort. She had helped shepherd passage of what is known as the Universal Prekindergarten law, and Davis saw her as a dynamic leader who could get things done.

From the start, Let’s Grow Kids distinguished itself from other public-policy campaigns. For one, it leaned aggressively into fundraising, ultimately amassing $77 million, a sum that included $42 million from individual donations, $20 million from government grants and contracts, and another $15 million from foundations and corporations. A good chunk of that went to help stabilize and expand existing childcare programs.

But the millions also funded a polished campaign, including television ads, yard signs and rallies, to raise awareness about the importance of early childhood education. In 2017, the group even produced a music video on Church Street featuring an original song by local musicians Kat Wright and Chris Dorman.

At its height, Let’s Grow Kids employed 35 staff; hundreds more volunteers acted as field organizers across the state. The organization convened a leadership circle to train early childhood educators how to tell their stories publicly.

Richards, a Vermont native who worked in Washington, D.C., politics after college, said she heard criticism about how much money Let’s Grow Kids was spending, but running a campaign that felt professional, and even slick at times, was part of the strategy.

“We were a nonprofit,” Davis said, “but we acted a little bit more like a startup.”

Having a 10-year deadline kept the organization disciplined and accountable, Richards said.

The pandemic likely helped the cause. Childcare centers were closed, and working parents were juggling Zoom calls with rambunctious kids in the room. Others had to stop working to take care of their kids.

Let’s Grow Kids leaned into the economic argument to help convince businesses: A better funded, more affordable childcare system would not just make life easier for parents and providers but would also enable companies to hire and retain a dependable workforce. The group called upon brain experts to boost the case for why high-quality early childhood education was critical to the success of society at large.

Some business leaders initially resisted taxation as a way to support a major investment in childcare, but they eventually came to embrace the idea of a payroll tax, leaving it to legislators to hammer out details. Act 76 levies a 0.44 percent tax on employee wages; employers can choose to shoulder the full tax themselves or pass on up to a fourth of that to their workers. The self-employed pay that smaller sum, 0.11 percent.

Republican Gov. Phil Scott ultimately vetoed Act 76, saying he could not support a payroll tax that he believed would unfairly burden lower-income Vermonters. But the Democrat-dominated legislature overrode Scott’s veto in a show of tripartisan support, securing a $125 million annual investment in childcare through a mix of payroll taxes and general fund revenues, thus paving the way for a possible transformation of the system.

Others, including former Burlington mayor Miro Weinberger, have drawn inspiration from the model. Earlier this year, Weinberger launched Let’s Build Homes, an organization aimed at addressing Vermont’s housing shortage. The name is no coincidence; Weinberger said he called both Davis and Richards to get their approval before he went public with it.

“We’re trying to do in a lot of ways for housing what they did for childcare: elevate this issue, change the narrative, educate Vermonters, think of housing in a new way and inspire action,” Weinberger said. “We’ll be fortunate if we can do what they did.”

Not Done Yet

If one had to select a poster child for the future of early childhood education, Alora Zargo would be a good choice. A first-year student at the University of Vermont, Zargo began working in childcare three years ago while a student at the Windham Regional Career Center. By the time she graduated high school in June, she’d earned 18 college credits in early childhood education.

Now 18, Zargo is taking four classes at UVM, where she hopes to graduate with a major in early childhood education or psychology.

“We’re molding the future generation,” Zargo said, “and helping children build pathways to become adults who can regulate and take care of themselves.”

Zargo has testified in the legislature about the importance of early childhood education. She hopes to return to the Statehouse to support a bill that would make it a more viable long-term career. That’s just one of the ways advocates are hoping to build on the legacy of Let’s Grow Kids.

The bill Zargo supports would require that early childhood educators be licensed by the state, according to three classifications based on experience and education. It also calls for fair compensation and benefits for workers.

The so-called professionalization bill didn’t make it to the finish line this year but is scheduled to be taken up again in 2026. One of its biggest proponents is the Vermont Association for the Education of Young Children, which represents teachers working in the field. The organization’s executive director, Sharron Harrington, said the bill is critical to ensuring the continued success of Act 76.

“Every new childcare space depends on having well-prepared early childhood educators in the classroom,” Harrington said.

Though many early childhood educators have rallied behind the bill, some have doubts.

Growing Tree owner Bishop, for one, worries that the legislation could penalize people who have experience in early childhood education but aren’t ready or able to go back to school to earn more credentials. Vickie Gratton, who owns two childcare centers in Swanton, is torn: She said her decision to go back to school for a bachelor’s degree after working in the field for decades made her a better educator, but she worries that more requirements might discourage others.

Sen. Becca White (D-Windsor), one of the supporters of the bill, acknowledges it may face an uphill battle to reach the governor’s desk.

In the meantime, childcare advocates say they have plenty else to focus on to cement earlier wins. One goal is to ensure that the money intended for early childhood education doesn’t get clawed back amid other state priorities and federal uncertainty.

Assessing the law’s impact and making necessary changes are also key priorities.

“Anybody who runs a business knows when you make a huge investment, it’s not just done,” said Michele Asch, chief people officer at Twincraft Skincare and a board member of Let’s Grow Kids Action Network, the spin-off organization that will focus on lobbying. “You have to keep tweaking it, making it better, evaluating what’s working and not working.”

Built into Act 76 is a monitoring process, led by Building Bright Futures, a nonpartisan state advisory group that reports its findings to the legislature each year. Its next report is due in January.

Dimitri Garder, the founder and former CEO of Bennington-based Global-Z, an analytics firm, is collecting data for Building Bright Futures to examine the impact of Act 76 on businesses.

“I haven’t heard anybody say, ‘Oh, it’s so much better since Act 76 has passed,’” Garder said. “They said, ‘Yeah, you know, it’s incrementally better.’” He acknowledged that it might take businesses longer than parents or providers to see the fruits of Act 76.

Garder points to Smugglers’ Notch Resort in Jeffersonville as an example of a company benefiting from the state’s investment in childcare. In 2022, Smuggs began offering free childcare to its employees at an on-site program to attract and retain workers. It has been able to continue only because of the state’s increased subsidy reimbursement, said Harley Johnson, director of children’s programs. The resort requires all new employees seeking childcare to apply for the state assistance; Smuggs then covers whatever the state does not.

Johnson said free childcare has attracted workers to all departments of the resort, from rental shop employees to housekeeping staff.

Even amid early signs of success, Davis, the founder of Let’s Grow Kids, is careful not to overstate them.

“Had I hoped it would be further along in this 10-year period? Yes,” said Davis. “Policy … and systems change takes time.”

Davis also concedes that Vermont’s challenges are many, from aging demographics and the housing shortage to the ailing health care system. He hopes that some of those issues can be addressed with the same ingredients employed by Let’s Grow Kids: strong leadership, resonant messaging and ambitious coalition building.

“We should be doing whatever we can to attract families, keep young people in the state of Vermont, and to make it possible for them to have children and raise their children here,” Davis said. Childcare is just “one piece of the puzzle.”

The original print version of this article was headlined “Growing Gains | Vermont’s bold investment in childcare is largely paying off”

This article appears in Nov 19-25 2025.