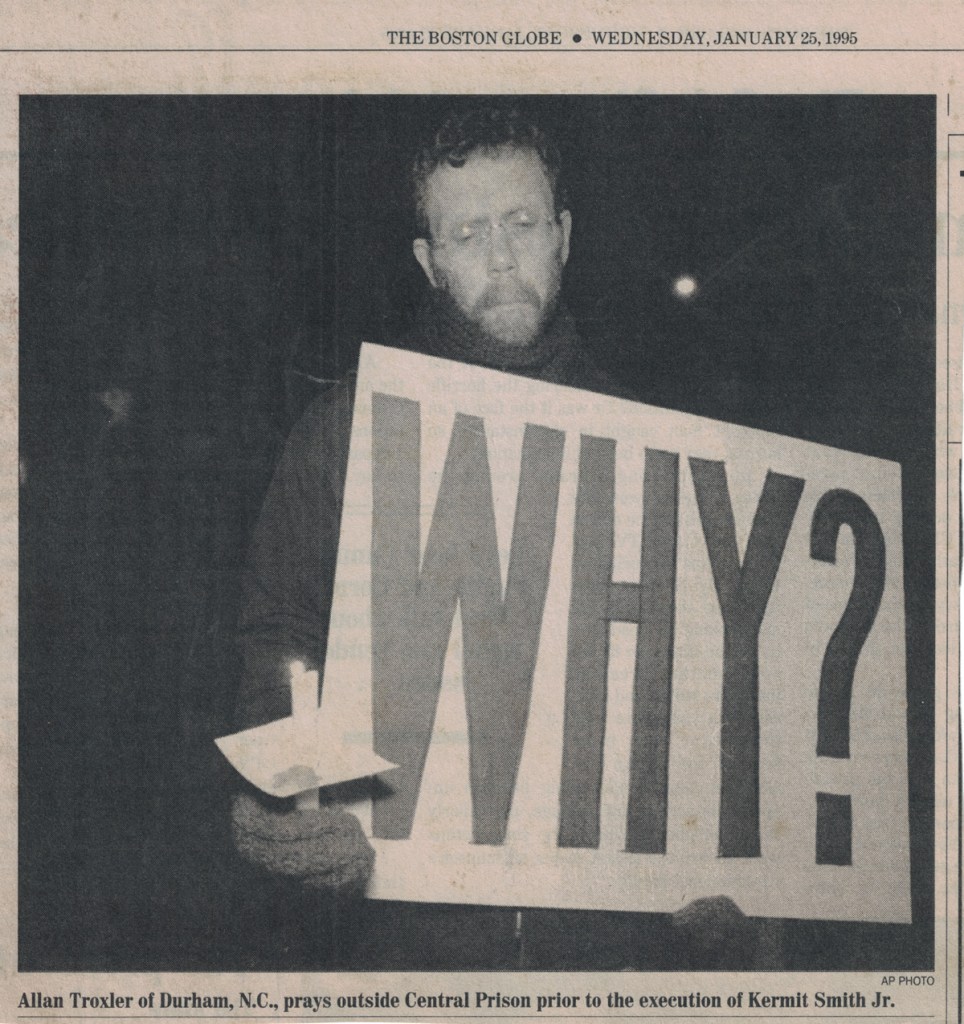

Over the past two years, Pamela George and Richard Ward spent hours in a small apartment off Broad Street sorting through boxes.

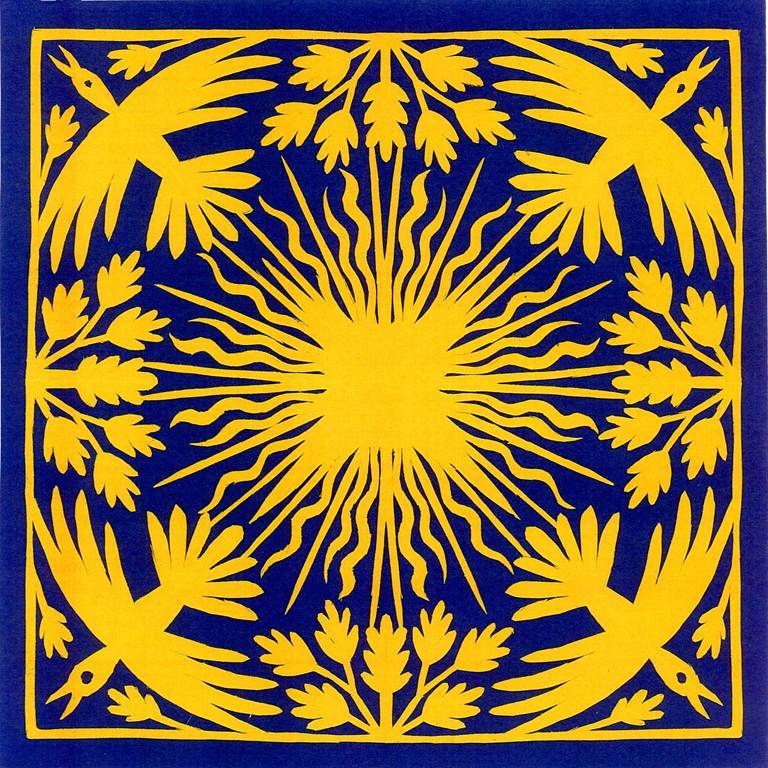

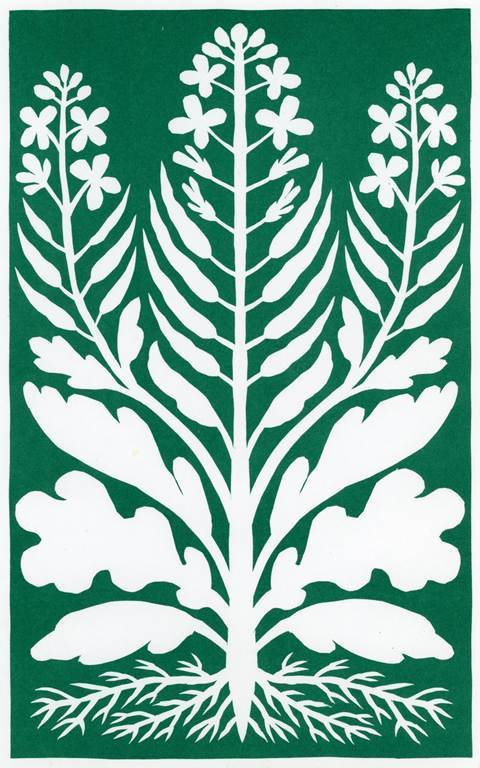

The material belonged to the artist and activist Allan Troxler, and it seemed endless. There were hundreds of Easter baskets and 50 pounds of birch bark. There was a hornet’s nest. Mostly, there was art: poems and political posters, textured sketches, and intricate paper cuts. As they sorted, George and Ward—close friends of Troxler’s—slipped materials into clear plastic sleeves for submission to Duke’s Rubenstein Library.

Troxler died in Chapel Hill on October 26, 2025. He was 78.

“We couldn’t have run the Left in Durham these many decades without Allan’s creative stamp,” says George, a Durham artist. “It was ubiquitous and also understated. He never promoted himself—there’s no website, no Instagram postings, no authorship. He worked in the quiet way, behind the scenes, in the most magnificent way.”

As Troxler’s friends tell it, the longtime Durham resident was a brilliant and undersung artist, a generous iconoclast who made and gave so freely that it is only in his death that the creative dust, flung widely around the region, has begun to settle. Troxler’s work braided the personal and political, touching on his experience of being a gay man in the South while illuminating the cost of war, the urgency of protecting the environment, and the monumental pleasures of dance.

“Allan [was] just an incredible person—one of the most incredible artists and activists, I think, that Durham has had in the last 50 years,” says Hooper Schultz, a community historian and doctoral candidate at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Troxler was born in 1947 in Greensboro to Eulyss and Catherine Kirkpatrick Troxler. When he was a child, the Klan left a burning cross on his family’s land outside Greensboro. His parents, who were Quaker and Methodist, were dedicated activists, and Troxler spent his early years posted up at antiwar vigils with his mother—a path he later followed as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War.

In the early 1970s, Troxler moved to a communal farm in Wolf Creek, Oregon, and became partners with Carl Wittman, an activist known for publishing the seminal document “A Gay Manifesto.” In Wolf Creek, the couple tended the land, engaged in environmental activism, and helped launch the publication RFD—an acronym that represented, depending on the issue, Rustic Fairy Dreams, Resist Fascist Demagogues, or similar variations on a theme. It is still in circulation.

In 1979, Troxler moved back to North Carolina because he missed his family and the “longer garden seasons” of the South, as he told the author and activist Mab Segrest, a close friend. He and Wittman settled in two dilapidated houses in East Durham, with Segrest and her partner joining Troxler in his home. They took to renovating Troxler’s home, and Segrest recalls turning sledgehammers to the walls—an act that was “therapeutic, in the early Reagan years.”

Beyond blunt instruments, there was beauty, which Segrest describes as Troxler’s “main medium.” He was passionate about gardening and English and Scottish country dance. Over the years, his friends came to know him as E. Bunny, a name drawn from his long-standing tradition of buying dozens of eggs, dying them wild shades, and then making elaborate midnight deliveries of Easter baskets across the Triangle.

Whimsy, talent, beauty—all these were elements in the drive from Troxler’s friends and family to preserve his materials, but it was about more than that.

“People my age—we understand that a generation is dying. It’s a generation that got us through all of these hard times to substantial victories that this MAGA group of folks is in the process of very effectively dismantling.”

mab segrest

In February, the National Park Service removed references to transgender people (including Durham’s Pauli Murray) from federal websites at the directive of the Trump administration; since then, a volley of executive orders challenging cultural institutions has followed, including efforts to censor museum exhibits, challenge school curricula, and revoke library funding. Entering things into the record has always been a political act, but these days, there is an electric urgency to it.

“People my age—we understand that a generation is dying,” Segrest says. “It’s a generation that got us through all of these hard times to substantial victories that this MAGA group of folks is in the process of very effectively dismantling.”

During 2024’s Pride Month, Governor Roy Cooper hosted a reception honoring Troxler alongside fellow activist Mandy Carter. Hooper Schultz helped recommend the pair to the governor’s office.

“Although Allan and Mandy are queer people who have organized around queer rights and against homophobia, they’re also people who are deeply concerned with all kinds of human rights and environmental issues and making the world a better place for all people. It’s really important for everyday North Carolinians to see the governor’s office recognize these people,” Schultz says. “It reminds them that they are here and have been here.”

In Durham, Troxler began working for the Institute of Southern Studies and, alongside Wittman, dove back into organizing around environmental issues and gay rights. The pair were early members of the North Carolina Gay and Lesbian Health Project and helped found Our Day Out, a protest precursor to today’s Pride March that was organized, at the time, as a response to the 1981 murder of Ron Antonevich in Durham by two men who took Antonevich to be gay.

One file, in Troxler’s archives, is full of letters—typewritten on paper eggshell-thin with age—from people around the country, written in response to an LGBTQ history proposal Troxler and Segrest spearheaded.

“I encourage your efforts to discover and present our previously invisible history,” one letter from Arkansas goes. “That invisibility here in the South is a particularly strong part of our oppression.”

In late 1985, Wittman was diagnosed with AIDS. The decline was rapid; he died a month later, by way of assisted suicide. A talented writer, Wittman might have been one of the ones to chronicle the wrenching story of a decade and keep it in public memory; instead, AIDS took his life, alongside the more than 700,000 people in the United States who have died from AIDS and HIV since 1980 and the 33 million who have died from the disease globally. Troxler became the keeper of Wittman’s archives, now also housed at Duke.

Some things changed in the years after Wittman died. Troxler saw the Durham Pride parade become annual, then mainstream; gay sex was nationally legalized in 2003 and gay marriage in 2015—events not far in the rearview mirror. He went on to have more romances; tended the gardens outside Blevins House, a group HIV and AIDS hospice home; and wrote long letters, in characteristic sloping handwriting, to friends dying from AIDS. By this past year, as Trump took office for the second time and a dangerous new wave of bigotry swept the nation, his dementia was advanced.

Kate Mitchell, Troxler’s niece, now lives in Durham but grew up in rural Western North Carolina. She remembers the reprieve, as a young queer person, of coming to visit her uncle in the Triangle. She also remembers stories her uncle told her of the early days, like one about a Duke professor marching in an early Pride parade with a bag over her head, fearing exposure.

“We may be entering an era where we’re required to take the kinds of risks that Allan was taking in the early ’80s,” Mitchell says. “It wasn’t the novelty of the celebration or the fun—it was fear, and it was making statements when you really didn’t know if that would affect your livelihood, your family. And we’re in a risky environment that’s increasingly similar.”

There’s a scene in Carson McCullers’s The Member of the Wedding in which three characters sit in a kitchen, exchanging ideas for a better world.

In the 1946 novel—the third from McCullers, a queer Southern writer—Frankie, a restless adolescent, feels like an outsider in her small town. The two people she is closest to are John Henry, her six-year-old cousin, and Berenice Sadie Brown, a Black woman employed by the white family. John Henry’s imagined world is a “mixture of delicious and freak” with rain made of lemonade, while in Frankie’s, people can “change back and forth from boys to girls.” Berenice wants a world without wars or lynching.

Segrest often had dinner with George and Troxler—the latter perpetually late, usually with an elaborate dish in need of assembling—and one night, as they sat on the floor, Troxler cracked open McCullers’s novel.

“It’s a gorgeous book that I hadn’t really been aware of, although as soon as Allan was reading it, I just felt like, ‘I’m Frankie. I remember, this is my life,’” says Segrest. Of the kitchen table scene, she continues: “It was this beautifully visionary sense of what the world could be if there weren’t Nazis and Klansmen in it, you know. I felt like I really connected with Allan in that way—throughout Southern literature, there’s Frankie Addams and John Henry West, there’s Scout and Dill. I felt like we were a little bit in tandem like that.”

“Seems to me that one big difference between the revolutionary and the fascist is that one tries to understand his own heart and one doesn’t.”

Allan Troxler in a note, circa 1969

At its best, creative work challenges what the artist David Wojnarowicz called “the preinvented world”—the restrictive blueprint of roles and rules we’re born into—and makes visible what has been hidden, allowing someone to read a passage and say, “I remember, this is my life.”

In one of the boxes at the Rubenstein, there is a folder of materials on an antiwar parade float, designed by Troxler, that was barred from a 1969 Greensboro holiday parade. The folder mostly contains newspaper clippings and photos, but there’s one sheet of notes from Troxler in the back. He sounds frustrated: “Doing posters and handbills—reaching everyone without reaching anyone,” goes one line.

But the scribbling continues, working out a thought: “Seems to me that one big difference between the revolutionary and the fascist is that one tries to understand his own heart and one doesn’t. I’m beginning to understand now that until you can love one person unselfishly, you can’t rightly act out of some generalized love you assume you have for your fellow man.”

Thanks to the alchemy of preservation, in all its forms, there can be no doubt about whether Allan Troxler tried to understand his own heart or love others unselfishly. The archive tells the story.

“He is part of the legacy of North Carolina, part of the queer legacy, part of the artistic legacy, and part of a spiritual determination not to be mowed down by the brutal forces that we grew up in and pushed back,” says Segrest. “And now they’re coming back again. So I think he is both rich anecdotally, but he is also rich as an antidote to all the things in this culture that could destroy us.”

Follow Culture Editor Sarah Edwards on Bluesky or email [email protected].