Bella Huang, a candidate for Cary’s District C town council seat in the municipal election this fall, tells a story about her son’s piano teacher who lives close by and is supporting Huang’s campaign with a sign in her yard.

Huang says the musician, a “strong Trump supporter,” surprised neighbors with the yard sign for Huang, a Democrat in an officially nonpartisan race (Huang’s opponent, Renee Miller, is active in the local Republican Party). It’s just one example, Huang says, of how she’s been able to build bridges with a diverse electoral base and head into early voting as the top fundraiser out of all six candidates running in Cary this cycle. She’s reported a haul close to $100,000, according to the most recent filings available, $30,000 ahead of the next most-moneyed candidate.

“She supports her values, that is totally fine,” Huang says of her piano teacher neighbor. “But for the local election, she’s just known me so many years, and she knows that I’m a good person, and I really care about everyone, so she supports me no matter what. It makes me very proud to share this story.”

Huang is one of two Chinese American candidates running strong campaigns for municipal seats in western Wake County. The other is Sue Mu, who is running for one of three open seats on Apex’s town council. Mu, as well, is leading in a pack of eight contenders in fundraising, netting close to $68,000, nearly four times that of her closest competitor.

“We’re out there, talking to the voters, talking to neighbors, attending all sorts of events to learn what our residents care about, what their concerns are, and what the government can do better,” Mu says of her campaign.

It’s no coincidence that Huang and Mu are making waves in local elections this year. Both have the weight of the Margin of Victory Empowerment Fund, a political action committee known as MOVE NC, behind them. MOVE NC is dedicated to encouraging political engagement among Asian Americans and championing Asian American candidates; Huang and Mu have been able to tap into a considerable donor base associated with the PAC.

They also have role models, including former Chapel Hill Town Council member Hongbin Gu and state representative Ya Liu, a former Cary Town Council member, who ran successful campaigns Mu and Huang say they’re learning from. Gu and Liu are two of the first Chinese Americans to hold elected office in North Carolina.

Finally, they have the support of many in a small but growing Chinese American population in Wake County, the Triangle, and the state more broadly—residents and voters who have been galvanized to fight back against the anti-immigrant rhetoric of President Donald Trump and, specifically, the anti-Chinese sentiment that followed the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I know that people I’ve spoken to were very concerned about [anti-Asian sentiment], and rightfully so,” says Shruti Parikh, the director of education and political engagement at North Carolina Asian Americans Together (NCAAT), a nonpartisan, nonprofit group that works to foster civic engagement and political participation among Asian Americans in the state (NCAAT also has a separate lobbying arm, NCAAT in Action). “And so, they mobilized. They created their [MOVE NC] PAC, which allows them to work together to ensure that their interests are funded.”

But it’s taken a while—at least a generation—to get here.

North Carolina’s Chinese American population, which represents about 15 percent of the state’s overall population of Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) residents, began growing in the 1990s and continues to grow, according to census and American Community Survey data.

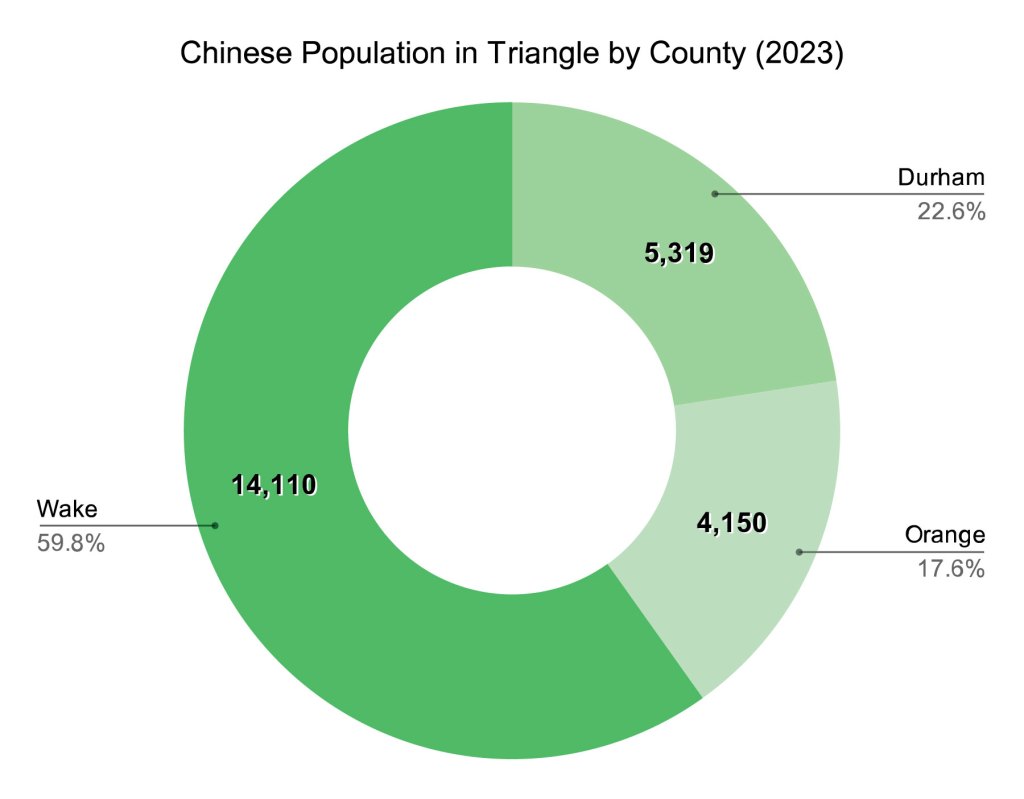

As of 2023, North Carolina is home to more than 360,500 AAPI residents, including more than 52,000 residents of Chinese origin. Most Chinese American residents—about 45 percent collectively—live in Wake, Durham, or Orange Counties, with the largest population (around 14,000) residing in Wake County.

Parikh says she doesn’t see that growth, or the community’s involvement in the political process, slowing.

“I’m talking to more and more Asian Americans across the state, and from different Asian American backgrounds, that are interested in running for office,” she says. “They see that others have blazed that trail ahead of them, and they know that with that success, that means that they can also bring their community’s interests forward and make sure that they have a seat at the table as well.”

In 1882, the national Chinese Exclusion Act specifically barred Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States and blocked Chinese immigrants from becoming U.S. citizens. Later, the U.S. Immigration Act of 1924 instituted four decades of racist national origin quotas that limited immigration from Asian and African nations. But in 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act, ushering in a new era that saw the quotas erased, skilled immigrants prioritized, and family reunification as a basis for immigration emphasized.

By the 1980s, North Carolina and the United States as a whole began to see increased migration from non–Western European nations, according to Nathan Dollar, the executive director of Carolina Demography at UNC-Chapel Hill. During the 1980s through the 2010s, he says, some 70 percent of all immigrants to the United States, and North Carolina, came from Latin American and Asian countries.

Of the AAPI communities, Indian Americans, who comprise the largest subgroup of Asian Americans in the state, quickly became the most politically organized, founding a nonpartisan PAC—NC-INPAC—three decades ago, according to Parikh. They’ve secured leadership positions within the state Republican and Democratic Parties, and Indian Americans, such as Morrisville Town Council member Steve Rao and state senator Jay Chaudhuri, have seen widespread electoral success at the state and, especially, local levels.

This election cycle, several Indian American candidates are running for seats on the Morrisville Town Council, including for mayor. People of Indian descent make up a majority—some 40 percent—of Morrisville’s population. Additionally, AAPI candidates are running for local office in Apex (in addition to Mu) and Wake Forest this cycle.

Gu, a former Chapel Hill Town Council member who was elected in 2017 and one of the founders of the MOVE NC PAC, recalls moving to the United States in 1994.

“When I arrived in this country, there weren’t really any Chinese or Asian organizations,” Gu recalls. “So it took a long time for us to gradually reach … the point that we are now in.”

“We came from a country that does not have the democratic system, so we know how important it is. We are just willing to put in our efforts, our resources, to make sure that we’re working together with other community members and others who believe in this vision for America.”

hongbin gu, former chapel hill town council member

Gu says community organizations slowly began to come together for Chinese American residents in the Triangle, including the Chinese-American Friendship Association (CAFA), a nonprofit cultural exchange group founded in 1996, and the Chinese School in Cary, founded in 2003. Events such as Chinese New Year galas and Cary’s Chinese Lantern and Taste of China festivals brought Chinese American residents together and facilitated connections between Chinese immigrants and the wider community.

On the state level, Asian American nonprofits, such as NCAAT, which formed in 2016, and various PACs such as NC-INPAC, existed to foster civic engagement and mobilize AAPI voters. It was a massive effort, explains Parikh. Following its formation, an NCAAT survey found that 80 percent of Asian Americans said they had never been contacted by either party in an election.

“And so we set out to bridge that gap,” Parikh says. They phone banked, knocked on doors, set up a hotline, and sent out mailers in eight different languages (there are between 20 and 25 spoken in the state’s AAPI community).

“In every election since 2016 we have worked hard to make sure that Asian Americans are increasingly aware of what elections are being held that year,” Parikh says. “The rise in [voting] numbers definitely shows that our engagement has been successful.” (In the 2024 general election, 92,886 “Asian” voters cast ballots, according to NC Board of Elections data; in the 2020 and 2016 general elections, those numbers were 75,060 and 51,516, respectively.)

It was around 2016, after Trump’s election, that Gu says it began to crystallize for her that, along with community organizations, Chinese Americans in the Triangle needed a political voice.

“We came from a country that does not have the democratic system, so we know how important it is,” Gu says. “So we are just willing to put in our efforts, our resources, to make sure that we’re working together with other community members and others who believe in this vision for America.”

Gu was elected to Chapel Hill’s town council in 2017, the first person of Chinese American heritage elected in North Carolina’s history. Then, in 2019, Ya Liu was elected to Cary’s town council. In 2022, Liu was elected to the state house, in District 21 representing western Wake County, with 68 percent of the vote. She is the first Chinese American elected to a North Carolina legislative seat, and, along with Wake County representative Maria Cervania, who is of Filipino descent, one of two of the first Asian American women to serve in the legislature.

In 2023, Liu, Gu, Bella Huang, and a group of Chinese Americans living in the Triangle, launched MOVE NC. The PAC’s name came to Gu while she was running in the woods one morning, she says. While Asian Americans make up a small number of voters, she reasoned, so many elections across North Carolina, at all levels of government, are decided by small margins.

“If we can encourage more people from the Asian American communities to get involved—do our voter registrations and education seminars and lots of trainings and make sure that people understand the issues, how important they are to their daily life and to their children, to the community—we can make a difference,” Gu says.

In addition to supporting Asian-American candidates and other candidates who share the PAC’s values—MOVE NC has fundraised for NC governor Josh Stein, attorney general Jeff Jackson, and lieutenant governor Rachel Hunt in past election cycles—MOVE NC also lobbies for and against legislation, in North Carolina and elsewhere, that impacts their communities.

Discriminatory laws in states like Florida ban Chinese nationals from owning property. North Carolina lawmakers filed a similar bill this session targeting Chinese citizens in an attempt to prohibit them from owning property, which MOVE NC has opposed (the bill is currently stalled in the state house).

Despite an emergent open hostility toward immigrants in the U.S. following Donald Trump’s reelection, the Asian American community isn’t a political monolith.

“There has been a rise in Asian conservatism, and we saw an influx of that with misinformation and disinformation on WeChat channels last year,” says Parikh of NCAAT. WeChat, similar to What’sApp, is used widely in Chinese communities. “I think that might be another contributing factor to why you’re seeing Chinese Americans running on a more progressive platform.”

Bella Huang and Sue Mu are two candidates trying to make a difference, and they have a lot in common. Besides being Chinese American women and MOVE NC PAC members—Mu is PAC chair and Huang, a co-founder, serves on the executive board—they’re both small business owners, working mothers, and community volunteers.

But, while bankrolled by many of the same donors, they’re running different races.

In Cary, as Huang’s story about her piano teacher might suggest, District C is one of the town’s older and more conservative districts. Although endorsed by the Wake County Democratic Party, Huang hasn’t made much of her party affiliation this election cycle.

“I just joined the Democratic Party when I registered my driver’s license at the DMV,” she tells the INDY.

Huang says the issues voters care about, including Cary’s Asian American residents, who make up slightly more than 20 percent of the population, include education—having good schools for their children and housing for teachers so they can afford to live in the town.

“We don’t have enough teachers, and I think that is one big issue,” Huang says.

For the Asian American community, Huang says, government services are another important concern.

“We care a lot about the parks, community centers,” she says. “Can we have enough pickleball or other community programs for us?” And, she adds, “people here will be a little bit worried about the increasing cost of living and increasing price of housing—which is not only in Asian American communities, it’s the whole community that’s worried about it.”

In Apex, Mu is more up front about her political affiliation. She’s running on a slate with two other Democrats—candidate Shane Reese and incumbent mayor pro tem Ed Gray—all three of whom have been endorsed by the county Democratic Party.

Mu is also up front about the difficulties of running as an Asian American candidate. She says she’s received harassing comments directed at her and her campaign, mostly anonymously online.

“Because I’m an immigrant and woman of color, some people … make nasty comments about my campaign … questioning my qualifications,” Mu says (she holds a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering and an MBA in finance). “They never asked any other candidates, only me, ‘Where were you raised and born?’ Recently, some people even left a comment [on a social media post about early voting], ‘Are you a U.S. citizen?’”

Mu released a statement on October 6 addressing the comment.

“These experiences only strengthen my resolve to keep bringing people together with respect, compassion, and courage—to make our country stronger and ensure Apex remains a welcoming home for everyone,” she wrote. “I’m running to serve, unite and empower all residents of Apex.”

Since then, Mu received about 45 more donations, she says, with 38 of those coming from Apex residents (those donations will be reported in the upcoming campaign finance filing period, posting before Election Day). Mu says she was heartened to see Apex residents stand up for her.

“They defended me,” she says. “Those nasty comments, and people behind those comments, are rare. Most Apex residents … are friendly. They appreciate how our immigrants can contribute to this country, how much we do, and they appreciate we are … hardworking people who contribute. So I feel touched.”

Mu says, if she gets elected, she’ll try her best to make Apex a welcoming place for everyone, “regardless of your skin color, regardless of who you love, regardless of which ethnic group you belong to.”

“It’s the best place. I love Apex so much,” Mu says. “There’s no other place I’d rather call home.”

Send an email to Wake County editor Jane Porter: [email protected]. Comment on this story at [email protected].