Florida will see its minimum wage rise to $14 per hour on Sept. 30, thanks to a ballot initiative approved by Florida voters in 2020.

And yet, the state has no state agency or division authorized to actually enforce Florida’s wage laws — meaning, if a worker believes their boss is failing to pay them all of what they’re owed, or is stealing their tips, they have very few options for recourse.

Since 2005, the year Florida first established its own state minimum wage in the first place, just one state official has had the authority to hold employers accountable for ensuring workers are paid at least minimum wage: Florida’s Attorney General.

Under Florida statutes, the state Attorney General has the power to impose a fine of $1,000 per violation, payable to the state, for any employer found to have willfully violated minimum wage requirements.

As Orlando Weekly has reported before, however, there is no evidence that the Attorney General’s office has ever done this in the 20 years they’ve had the authority to do so. A report from the Economic Policy Institute found that Florida has the highest minimum wage violation rate of the 10 most populous states in the country, and research indicates that as the minimum wage goes up, so too do employer violations.

An analysis by the Florida Policy Institute and Rutgers University’s Center for Innovation in Worker Organization found that, after Florida’s minimum wage increased in 2005, the state’s minimum wage violation rate more than doubled to 17 percent by the end of 2007, disproportionately affecting workers in agriculture, real estate and the service industry.

Establishing a strong enforcement mechanism for catching minimum wage violations, and holding violators accountable for cheating workers of their hard-earned wages, however, hasn’t been a priority of the state Attorney General’s Office. The office, currently led by Gov. Ron DeSantis’ ally James Uthmeier, doesn’t even mention on its website that it is the only state agency that is able to do so.

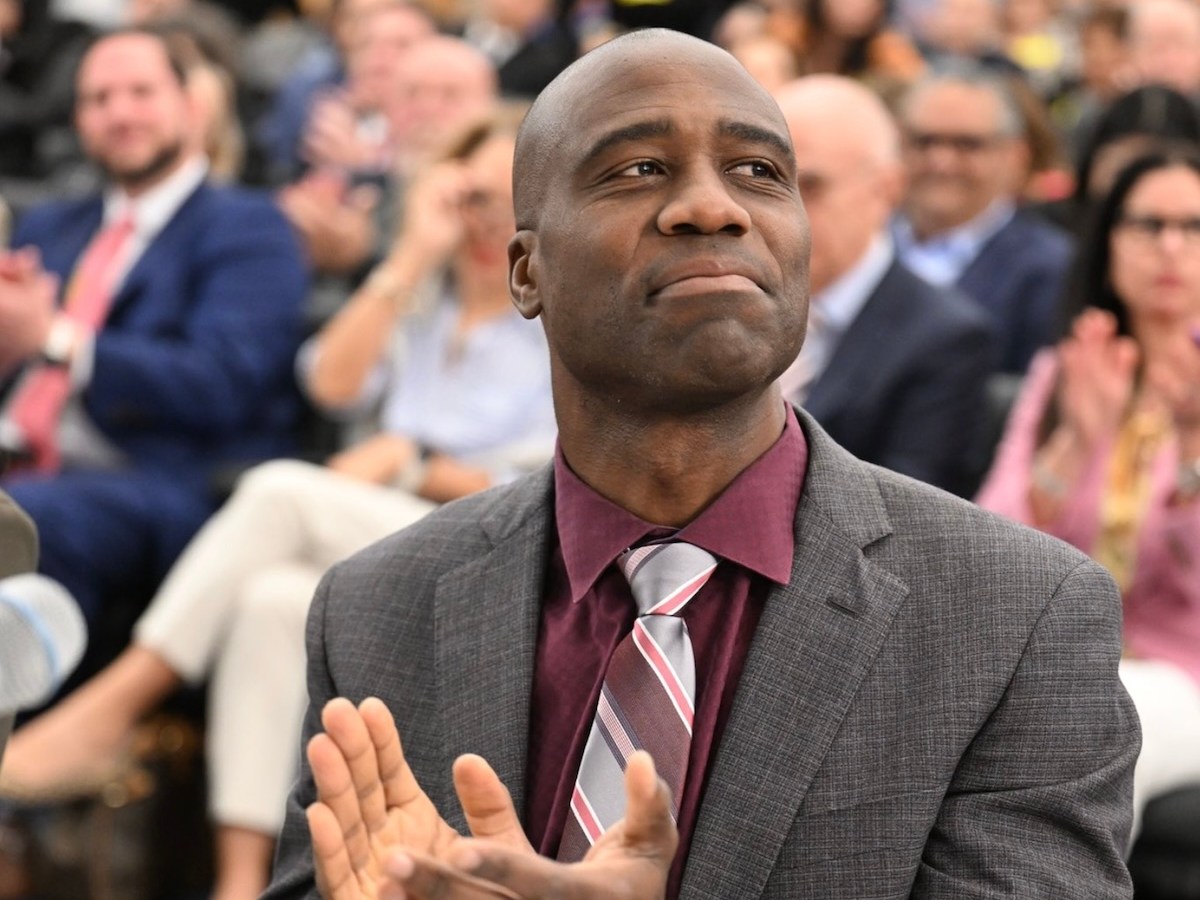

Jose Javier Rodriguez, a workers’ rights lawyer and former Democratic state senator who’s running in 2026 to replace Uthmeier, wants to change that.

“For decades, the Attorney General’s Office has functioned to prop up the powerful and corrupt and not to look out for the people,” Rodriguez told Orlando Weekly in an interview. “State attorneys general routinely enforce state labor laws, including state minimum wages, routinely bringing actions on behalf of defrauded workers — except in Florida,” he said.

The wild west of labor law

According to the Workplace Justice Lab at Rutgers and Northwestern University, U.S. workers lose tens of billions of dollars each year from being paid less than their state’s minimum wage. And Florida, a state with a workforce of more than 11 million, including roughly 1 million workers earning minimum wage, is uniquely vulnerable.

Former Gov. Jeb Bush dismantled Florida’s state department of labor more than 20 years ago, abolishing the only state agency tasked with enforcing the state’s wage and hour laws. No replacement for the former state agency has been established in Florida since, despite repeated efforts by Democratic state lawmakers who are in the minority in the Florida Legislature.

“The minimum wage has largely been unenforced for, really, as long as Florida’s had a minimum wage,” Alexis Tsoukalas, a policy analyst for the Florida Policy Institute who’s co-authored reports on the issue, previously told Orlando Weekly.

Indeed, the Nation reported back in 2016 that then-state AG Pam Bondi — currently serving as U.S. Attorney General under President Donald Trump — took no action to hold employers responsible for violating the minimum wage in Florida for years. Records obtained by the Weekly show her successor Ashley Moody didn’t do much to hold employers responsible for this either.

In 2023, for instance, her office helped just one person — a Hungry Howie’s pizza delivery driver — recover about $500 after the assistant attorney general from Moody’s office sent an ominous warning to his employer. Still, the office didn’t take any official enforcement action to get the spooked employer to pay up. Nor did his employer, a franchisee in Hudson, face any penalty for violating Florida’s minimum wage law in the first place.

“I recommend that you make private efforts to remedy any other employees whose wages were similarly underpaid to avoid further complaints being levied against you,” then-Assistant Attorney General Rebecca Snyder wrote in an email to the Hungry Howie’s franchisee, obtained by Orlando Weekly through a public records request.

“The minimum wage has largely been unenforced for, really, as long as Florida’s had a minimum wage”

Alex Tsoukalas, Florida Policy Institute

It’s unclear whether Florida’s current AG, Uthmeier, has a firm position on the issue himself. Uthmeier, a 37 year-old Republican who formerly served as DeSantis’ chief of staff, was appointed by DeSantis to become Attorney General in February to fill a vacancy left by Moody, who was similarly appointed to fill former Sen. Marco Rubio’s seat in the U.S. Senate.

Orlando Weekly requested records from the state Attorney General’s Office in June, under Uthmeier’s leadership, asking for minimum wage complaints their office has received over the last year and any actions they’ve taken to address them. Despite an initial acknowledgement of our request, and multiple follow-ups, the office has failed to produce any records responsive to our request as yet.

As Rodriguez pointed out in our interview, it’s not unusual for state attorneys general and other state officials elsewhere to take on the responsibility of cracking down on wage theft.

In Rhode Island, a state with a workforce roughly 20 times smaller than Florida’s, the Attorney General’s Office received more than 300 “actionable” cases of wage theft last year, and recovered nearly $1 million in owed wages. The small, Democratic-led northeastern state actually has its own state labor department, unlike Florida, and recently moved to make willfully committing wage theft a felony offense, up from a misdemeanor.

Over a two-year period, Massachusetts’ Attorney General secured over $2.8 million in back pay for more than 3,000 workers in the construction industry alone, in addition to $1.7 million in penalties from employers, payable to the state.

New York State Attorney Letitia James has similarly taken an aggressive approach to the issue — for instance, reaching a $16.75 million settlement with DoorDash for wage theft earlier this year. She’s also recovered unpaid wages and tips for nail salon workers, bar employees, and Uber and Lyft drivers, among others.

The state of New Jersey — albeit, independently of its Attorney General’s office — even has a digital wall of shame (“Workplace Accountability in Labor List”) for employers who commit wage theft and other violations.

Trouble on the horizon

The idea that employers can illegally cheat workers of their lawfully earned wages in Florida without facing repercussions is a thought that is especially troubling, with Florida’s minimum wage set to go up at the end of the month.

Under a ballot initiative approved by nearly 61 percent of Florida voters in 2020, Florida’s minimum wage is on a gradual path to reach $15 next Sept. 30. It’s currently $13 for non-tipped workers, and $9.98 for workers who earn tips. On Sept. 30, 2025, that minimum hourly rate will rise to $14 for non-tipped workers and $10.98 for tipped employees.

State Attorney General candidate Rodriguez, who most recently served as U.S. Assistant Secretary of Labor under President Joe Biden, is keenly aware of the lack of attention in Florida to the issue of wage theft. A longtime employment lawyer, Rodriguez joined other worker advocates roughly 20 years ago as they sought transparency on minimum wage enforcement from the state Attorney General’s Office.

“I will tell you the very first time I engaged with the Attorney General’s office back then, it probably would have been in 2006 or 2007, I distinctly remember them not knowing what I was talking about, that they denied having the authority to enforce the minimum wage,” Rodriguez recalled.

“Quite frankly, it sucks.”

Morgan & Morgan attorney Ryan Morgan

A decade later, the work continued. “The attorney general’s office is simply not enforcing the minimum wage in the way that other states do,” Rodriguez told ABC News affiliate WTXL in 2015. “We basically have it in the constitution and we have it in the books, but as far as any state enforcement … that is it.”

Floridians first voted to establish a state minimum wage, separate from the federal minimum wage, in 2004. At the time, the federal minimum wage was $5.15 an hour.

Although federal investigators in the U.S. Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division are authorized to investigate complaints of wage theft in Florida (including but not limited to minimum wage violations), they are only authorized to recover wages up to the federal minimum wage — which currently sits at just $7.25 an hour.

Plus, the federal Wage and Hour Division is understaffed and overburdened. As of May, the division had fewer than half the number of investigators it had at its peak in 1978, according to a recent analysis, despite the fact that it’s today tasked with protecting the rights of three times as many workers.

In the absence of help from the state government in combating wage theft, some community organizations — including the Farmworker Association of Florida — have stepped up to help fill gaps. In addition, at least a half-dozen local municipalities in Florida, including Osceola County, have established their own local wage theft programs.

Rodriguez was part of the effort to create Florida’s first local wage recovery program in Miami-Dade County back in 2010, as part of a coalition of groups in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. In just the first year alone, the program resulted in more than 600 prosecutions and $1.7 million recovered in stolen pay, the New York Times reported at the time.

“The county didn’t have a big budget,” Rodriguez recalled. “So the design that I came up with for these groups was sort of based on almost like code enforcement, right? It’s a self-enforcement thing. You get a hearing officer, you get an order that then can be turned into a court order, but you don’t need a lawyer. What you get is you get an opportunity to come in and prove your case in front of a hearing examiner, and then you can go ahead and enforce it,” he explained.

Since employment lawyers have a low acceptance rate for wage theft cases as it is — especially instances of wage theft that only involve a few hundred or thousand dollars — the importance of having an alternative program is important.

“Our acceptance rates on the wage and hour cases are below 10 percent,” Morgan & Morgan attorney Ryan Morgan previously told Orlando Weekly, adding that this is in line with acceptance rates of other firms.

“Even we just don’t have enough manpower and hours of the day to handle every case. And so when you’re looking at it, you do have to make difficult choices at times,” Morgan added. “And quite frankly, it sucks.”

Vying to become Florida’s next chief legal officer

Florida’s Attorney General is an elected official who serves as the state’s chief legal officer, responsible for protecting Floridians from fraud, enforcing antitrust laws, defending the state in civil litigation cases, and going after criminal activity such as drug trafficking and identity theft.

The AG is typically elected by Florida voters every four years. Uthmeier, a Republican, was appointed by DeSantis to fill the remainder of former AG Moody’s term earlier this year following her own appointment to the U.S. Senate. His current term ends in January 2027.

Rodriguez, based in the Miami area, faces an uphill battle to defeat Uthmeier. As the incumbent — who routinely finds himself in headlines for his enforcement of the state’s harsh immigration policies — Uthmeier has name recognition. He’s a Republican, backed by his party in a state where the GOP currently has a more than 1 million edge over Democrats in voter registration.

Rodriguez, who’s running on an anti-corruption platform, was first elected to the Florida House in 2012 before running for the state Senate in 2016, where he served for four years. Rodriguez in 2020 narrowly lost his bid for re-election to the Florida Senate by just 40 votes to Republican Sen. Ileana Garcia, after corporate interests reportedly paid a “ghost” candidate with the same last name as his to run as a no-party candidate against him.

“It came out that [Florida Power & Light] was the funder of that, and the reason why they were so upset with me is because there was nobody else in state government standing up for their customers and against them than me,” said Rodriguez, who had filed legislation in 2019 that FPL opposed. “They wanted to take me out,” he continued. “And I think that, you know, if voters want any proof that they’re going to have a fighter in the Attorney General’s office, I think that’s it.”

Subscribe to Orlando Weekly newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Bluesky | Or sign up for our RSS Feed

Related

Source link