According to recent Gallup polling, public support for labor unions in the U.S. is at a near-record high, with 68 percent of U.S. adults voicing approval. And yet here in the Sunshine State, and the broader U.S. South, the percentage of workers who are actually represented by a union is dismally low. Although union representation has been linked to higher average income and greater access to benefits like paid time off, the power of Florida’s labor movement has been stunted by a decades-old policy agenda historically hostile to labor unions, multiracial solidarity and basic worker rights, including Floridians’ right to a minimum wage and a right to safety on the job.

Still, history shows us that the so-called “non-union” South isn’t immune to the power and solidarity of working people who are willing to fight (sometimes literally) for safe working conditions and fair pay on the job. For the 2025 Global Peace Film Festival, Academy Award-winning director Barbara Kopple will bring her classic class-struggle documentary Harlan County, USA directly to an Orlando audience this week. The film, first released in 1976, offers a graphic, gritty and eye-opening depiction of a 13-month strike by Duke Power Company coal miners (a company we know today as Duke Energy) in Harlan County, Kentucky.

The film, a must-see for labor history buffs (like this reporter), documents the bitter 1973 miners’ strike at Harlan County’s Brookside Mine. The strike began in part due to the utility’s failure to recognize the workers’ formation of their union, affiliated with the United Mine Workers, spurred by the draw of benefits such as healthcare, paid leave and a pension. It ended shortly after a 22-year-old striking miner was murdered by a (non-union) mine supervisor, tragically leaving behind a 16-year-old widow and their baby.

Notably, not only do the miners play a starring role in the film, but so too, do the miners’ wives, who organized around the notion that they didn’t want to see their husbands die from preventable diseases like black lung or inside the mines. The group played a critical role in drumming up morale and making the miners’ fight a community fight. “The strikers … generally believe that the women — along with the $100 a week in strike benefits each worker gets from the [United Mine Workers] — have been the main reason that the strikers have been able to hold out so long,” the New York Times reported nine months into the strike in May 1974, noting that the women spoke of their “picket line skirmishes” with “a kind of revolutionary fervor.”

Kopple, who’s currently working on a new film, graciously agreed to an interview with Orlando Weekly to discuss the relevance of Harlan County, USA for today’s audiences, as well as Gumbo Coalition, a 2022 film of hers that will also screen at the Global Peace Film Festival. The GPFF, first established in 2003, will show 20 films from Sept. 16 through Sept. 21 at Enzian Theater, Rollins College and the Winter Park Library.

We have more details on the festival below. But first, our interview with Kopple herself:

How did you get involved with the Global Peace Film Festival?

I have heard about the festival for years from my friend Nina Streich. She is the head of the festival, and a remarkable person. She is passionate about social justice films, and shows wonderful work there that ordinarily people outside big metropolitan areas would not get a chance to see. It is a space for community members to come together and discuss the issues that matter. I am honored to screen my work here.

Why did this feel like the right year to bring Harlan County, USA and Gumbo Coalition to GPFF?

Gumbo Coalition is about two dedicated civil rights leaders [Marc Morial and Janet Murguía] on the frontline of the fight for justice, which nowadays feels more urgent than ever. In this very polarized time, it is so important to understand different perspectives, to listen to each other and witness the hardships of so many in our communities. I hope that the leaders portrayed in the film and their strength and passion can inspire others to step up, speak out and help build a more equitable society.

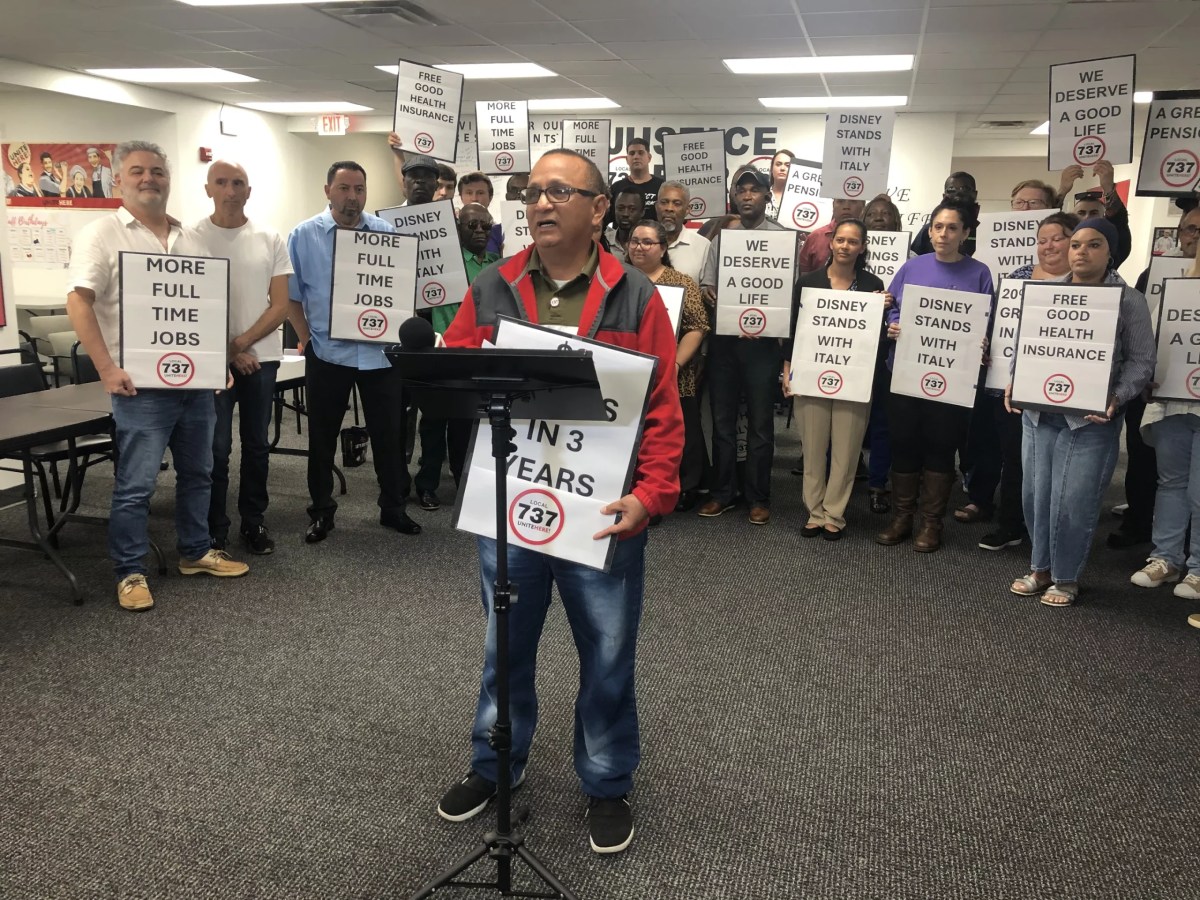

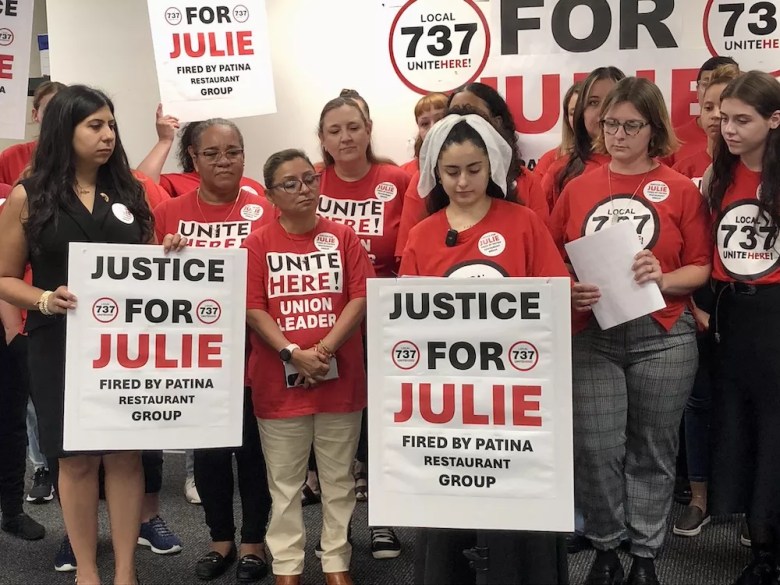

Harlan County, USA, too is so relevant, as unions have been rising up everywhere, from autoworkers to delivery workers to actors and screenwriters and fast food workers, to name just a few.

What lessons do you think workers in the South (including Florida) can take from Harlan County, USA today, nearly 50 years after its release?

In states like Florida, and in so many places across the country, union density is low but there is a huge need to protect workers. The people of Harlan County stood together, even in the hardest of times, and I hope this film shows others that they have strength in numbers, and that they can win even if the challenges seem insurmountable.

One lesson from the film is the role of women and families. They stand on the picket lines along with their husbands, keeping the spirit alive. It shows something very important in organizing: that it’s about families and communities that have your back. Broad solidarity is something we need everywhere, especially in places where immigrants and women are at the heart of the workforce.

What do you believe has changed in the South’s organizing landscape, and what hasn’t?

The landscape of work itself has changed, but the struggles remain the same. On the picket lines in Harlan County, people were shot at and intimidated. Today, companies hire union-busting firms to ensure the union’s progress will be stifled, and they pay these firms millions of dollars in exchange. But many unions are fighting back; while in Harlan County, our camera was there, nowadays workers use social media to organize and tell their own stories. Shedding light on injustice for me is often the first step to try to change it.

You were about 30 years old when this film was released, so I’m curious: What drew you to this story? And, for our readers who are similarly interested in film production, what were the biggest challenges you faced in filming and bringing this to the screen?

I heard about a coal miner named Arnold Miller, coming out of the coal mines and running for the election of the president of the United Mine Workers. He wanted to make big changes, he wanted to do something about black lung, mine safety, a decent wage, and he was running against [William Anthony] Tony Boyl, who was in collusion with the coal operators. I filmed Miller’s campaign; his promise was to organize the unorganized. In Eastern Kentucky, there was a strike and I wanted to see if he would make good on his promise to support the workers there.

Once I arrived in Eastern Kentucky and met the women and men on the picket lines, I became drawn into their lives, and ended up living there for 13 months. We were shot at with semi-automatic carbines, a coal miner was killed by a company foreman, and it was dangerous — people lived and died by their guns. When I told my parents what was happening, my mother forbade me to stay there another day, but I told her I was only kidding. She said, “Don’t ever kid around like that again.” We also had no funding, and I had to use a credit card to try to make this film.

I hope the audience leaves inspired and ready to take part in organizing and making something better.

Barbara Kopple

Orlando’s economy is dependent on our tourism industry, which employs about one-third of the region’s workforce. What do you think tourism workers, many of whom are low-wage and lack union representation, have in common with the workers and families featured in your film? What lessons can a local bartender, housekeeper or character performer take from this film?

The industries may be different, but the feeling of being undervalued, underpaid or easily fired, are much the same. In Harlan County, coal miners died from black lung disease. An activist recently told me her best friend died because she inhaled so much bleach cleaning other people’s homes, and her lung was damaged. When Covid hit, she died. There was no protection for her or her family, because she was not an employee, and undocumented.

But I have learned that even undocumented workers here [in New York] are organizing each other; some of them have fought in great numbers, together, to pass bills that protect even the most vulnerable workers, and they have had significant victories. Some of them organized … their own OSHA classes for newly arrived immigrants. This can be the first step of community-building, and a step towards eventual union representation.

What do you hope for a local audience here in Orlando, Florida (a state with one of the largest immigrant populations in the U.S.) to be able to take from your film Gumbo Coalition?

I hope people take away that whether you’re an immigrant, a young activist or someone who is really passionate about making change, that your voice matters, and that coalitions between people of different backgrounds can be powerful. I hope the audience leaves inspired and ready to take part in organizing and making something better.

Is there anything you can tell us about the project you are currently filming?

My new film is a portrait of modern labor today. Like with all my films, it’s about being close to people and their families, following workers as they move through very turbulent times. I always strive to show their resilience, dedication and the sheer hard work it takes to keep the movement alive.

Harlan County, USA screens at 5:30 p.m. Friday, Sept. 19, at the Bush Auditorium at Rollins College. Gumbo Coalition, following civil rights leaders Marc Morial and Janet Murguía, screens at 7 p.m. Thursday, Sept. 18, at the Bush Auditorium. Tickets are $10 each.

Find more information about the 2025 Global Film Festival and purchase tickets at peacefilmfest.org.

Subscribe to Orlando Weekly newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Bluesky | Or sign up for our RSS Feed

Source link