The Green River Reservoir cast its spell on Bryn Davis five years ago, and he and his family have been back every summer since.

They love the adventure of paddling a canoe packed with camping gear toward a distant wooded shore. They marvel at the loons diving into the pristine water and the stars shimmering in the night sky. Thanks to the prohibition on motorboats, they appreciate the profound sense of peace that pervades the remote area in Hyde Park.

“It’s a special place,” Davis, a software engineer from Hanover, N.H., said last month as he loaded his canoe at the crowded boat launch at Green River Reservoir State Park. “Especially in the evening and early morning, it’s unbelievably quiet.”

Beneath that tranquil surface, however, a fierce battle has been raging for more than a decade over the future of the beloved reservoir and the concrete dam that created it nearly 80 years ago.

State regulators have been trying for years to get its owner, the local electric utility Morrisville Water & Light, to run the dam in a more environmentally sensitive way. The utility is seeking to renew the hydro dam’s federal license, a lengthy process that allows the state to have water quality requirements included in the new permit. In this case, Vermont has written strict new operating rules to regulate the volume of water that flows out of the reservoir in order to improve wildlife habitat in the reservoir and in the Green River.

Utility officials have pushed back hard.

They argue that the new restrictions offer little environmental benefit; would force the utility to abandon a source of cheap, clean electricity; and would ultimately lead to higher electricity rates. They have sued regulators in state and federal courts, claiming the restrictions weren’t based on sound science. They asked lawmakers to intervene, too — all to no avail.

Now, the utility says it’s done fighting: It intends to surrender its federal license, though it hasn’t yet filed a formal plan to do so. The company also wants the state to take over the dam and the expense of running it. State government has commissioned a nearly $600,000 study of that possibility, and a report is due soon.

“The state has decided to regulate Green River out of existence,” said Scott Johnstone, general manager of Morrisville Water & Light. “We’re done. Time to move on with life.”

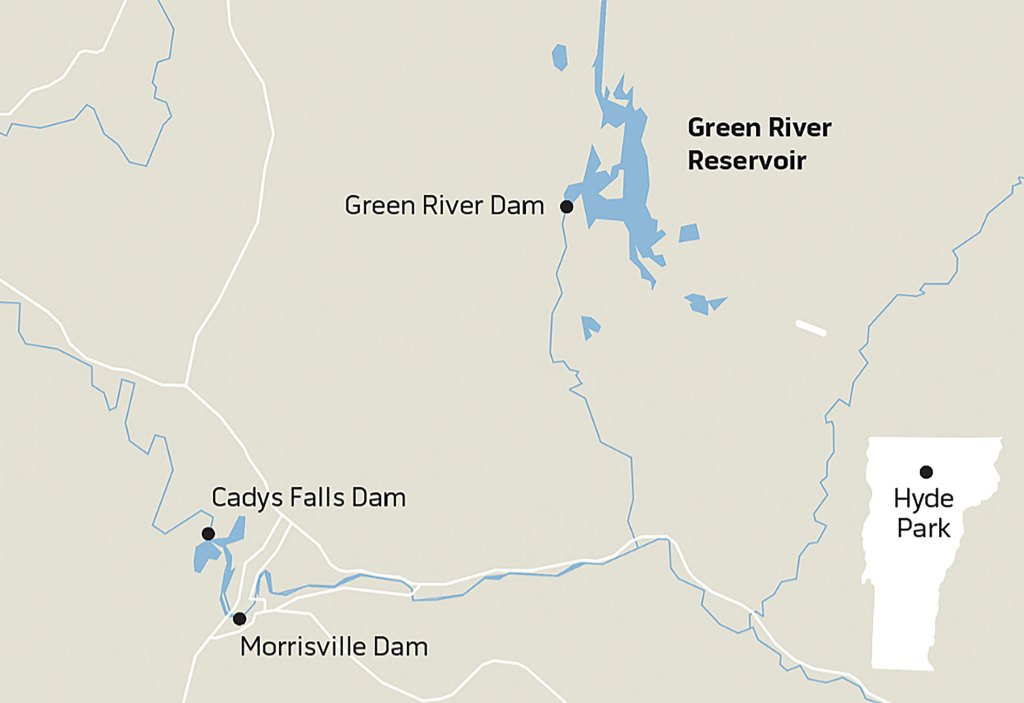

The utility will focus on relicensing its two larger hydroelectric dams, Morrisville and Cadys Falls on the Lamoille River, he said. The utility will also have to find a new source to replace the electricity produced at the Green River plant, which amounts to 2 percent of the power its 4,800 customers use.

If Green River’s turbines stop spinning, the utility may have to rely more heavily on power from carbon-emitting sources on the New England electric grid, which Johnstone said would make it harder for the utility — and the state — to reach its climate goals.

“It feels like we’re getting forced to take a step backward,” Johnstone said.

The situation is the highest profile example of the increasing tension between clean water and clean energy. Morrisville Water & Light is not the only hydroelectric operator facing tougher operating requirements that reduce energy output. More than two dozen Vermont dams have been relicensed in the past 25 years, and many of them now make less electricity than they once did.

Water quality advocates say the state is rightly clamping down on hydro facilities during a lengthy federal relicensing process that can lock in operating conditions for 30 to 50 years.

But renewable-energy advocates say that’s a huge problem. Vermont imports about 80 percent of its power, but about 56 percent of the electricity generated within Vermont comes from hydro. Except for spikes during unusually wet years in 2023 and 2024, hydro generation in the state has remained fairly stable for more than two decades.

A reliable source of electricity for Vermonters since the late 1800s, hydro is seen as key to balancing the intermittent output of wind and solar farms. The state has a goal to draw 100 percent of its electricity from green sources by 2035, including a higher percentage from in-state generation. Even a small drop in power production from local dams, advocates say, undermines this drive to clean up Vermont’s power supply.

“I firmly believe we can have hydropower that is also thoughtful about its impact on water quality.”

Natural Resources Secretary Julie Moore

The potential demise of the Green River hydro is unfortunate but may have been preventable, according to Vermont Natural Resources Secretary Julie Moore. Had the utility taken a more collaborative approach instead of the litigious, confrontational one it adopted early on, a compromise to keep the electrons flowing from the Green River dam might have been possible, she said.

“The challenge with Morrisville was it was an all-or-nothing proposition,” Moore said. “It was, ‘You guys are wrong, and we’re going to fight you to the death on this.’”

As old dams built with little consideration for the health of rivers face federal relicensing, it’s important they be closely scrutinized by the state to better protect waterways, Moore said. This “rebalancing” is difficult and takes considerable effort and problem solving, but in most cases can be achieved.

“It is a challenging balance to strike between our clean energy goals and our clean water goals,” she said. “But I firmly believe we can have hydropower that is also thoughtful about its impact on water quality.”

Cash Flow

Most visitors to Green River Reservoir State Park give little thought to why the 653-acre body of water exists. They pull into the dirt parking lot, check in at the rangers’ station, haul their canoes and kayaks down to the boat launch, and paddle off.

The park, created in 1999 when the state purchased the reservoir and 5,100 acres of forest around it, has 26 campsites on islands and along the undeveloped shoreline. The sites can only be reached by water and are so popular that they get booked for the summer minutes after they become available.

A few hundred yards past the park entrance, behind a locked gate down a steep gravel access road, sits a monstrous chunk of curved concrete, 105 feet tall and 360 feet long, that blocks the river’s natural path.

The aging structure’s face is streaked with a mix of rust and efflorescence, a powdery white substance that collects on older concrete, sections of which have flaked off. Two rusty pipes, relics of another era, run from the top of the dam to the riverbed below. A tiny concrete structure with metal shutters at the base of the dam looks like the abandoned home of a deranged hobbit.

What the complex lacks in aesthetic appeal it makes up for in usefulness.

Morrisville Water & Light constructed the dam in 1947 but not to generate power there. The idea was that during times of drought or high electricity demand, operators could release water from the new reservoir to boost power generation at the hydro plants downstream. It was only in 1983 that the utility added turbines at the dam itself. Today, the water that powers those turbines continues downstream to generate more electricity at the Lamoille dams.

Water is released from the Green River dam through a 54-inch pipe and can flow through one or both turbines, depending on how much power is needed. The turbines are like huge hamster wheels lying on their sides, retired dam operator John Tilton said during a recent tour.

The water shoots into the turbines, hits the curved blades, and turns 945-kilowatt generators above them. Its energy spent, the water then drops down into what is called a tailrace and back into the rocky river bed.

When both turbines operate at full power, so much water flows through them and back into the Green River — upwards of 500 additional cubic feet per second — that a four-foot-wide culvert a mile and a half downstream used to get overwhelmed, Tilton said. That’s why operators usually run just one turbine at a time.

The utility operates the turbines in short bursts primarily to “beat the peak,” Johnstone said. This means that when power is in high demand and the cost of buying it from the grid is expensive, the utility generates more of it at Green River.

The reservoir is like a huge battery that the utility can draw from when needed. The concept is similar to the way residential solar systems are often paired with batteries that can discharge power after the sun goes down and hydro systems that pump water uphill when renewable energy is abundant and release it to pass through turbines downhill when power is needed.

At times, particularly when summer temperatures soar and large numbers of people turn on their air conditioners, spot energy prices can reach $1 per kilowatt hour. But Morrisville Water & Light can generate power at Green River for around 18 cents, Johnstone said.

Not only is the electricity cheaper, he explained, but the utility also saves on transmission costs charged by the grid, which are based on the peak loads.

Level Best

Treating a river system like a huge battery creates problems for the creatures that live there.

Loons, for example, are very sensitive to fluctuations in water levels, said Eric Hanson, a biologist with the Vermont Loon Conservation Project. They build their nests just a few inches from the waterline, so raising or lowering the level slightly can flood nests or strand chicks.

Morrisville Water & Light tries to keep the water level stable during loon nesting season, generally May through June. The utility can still generate power, but the amount of water allowed to run out of the reservoir through the dam has to approximately match the volume flowing into the reservoir from the Green River — which can vary significantly based on rainfall.

That practice has paid off. In 1983, the reservoir was home to just one nesting pair of loons. Today, there are four, with a large number of nonbreeding birds also hanging out, Hanson said. That suggests that not only are the nesting conditions good, but the fish population that the loons feed on is also healthy. “Overall, loons are doing pretty well,” he said.

The dam created this prime habitat for loons. But operating it to generate electricity harms other species.

While native brook trout love cold water, the inconsistent pulses of frigid water drawn from the base of the reservoir throughout the year damages their habitat, said Karina Dailey, a restoration ecologist with the Vermont Natural Resources Council.

“It’s a shock to a system that’s really not healthy for the fish,” Dailey said.

In the summer and fall, the utility is required to limit drawdowns, as they are called, of the reservoir’s levels to one foot. In the winter, the limit is 10 feet, as long as it’s refilled by May 1. In reality, the utility usually draws the water down no more than six feet to ensure that the spring runoff will be sufficient to refill the reservoir, Johnstone said.

That six-foot drawdown is valuable because home heating can lead to high electricity rates in winter. But such drastic drawdowns, even when done gradually in a series of short bursts, can blast the riverbed below the dam. And they can cause exposed sections of the reservoir bottom — 80 acres, biologists testified in court — to dry out and freeze, killing bugs such as mayflies that are a key part of the food chain. The reservoir’s shallow areas contain fewer insects and less vegetation than natural lakes and ponds, evidence showed. Johnstone argues that the fluctuations mimic those in natural river systems.

Concerns about wildlife habitat drove regulators to propose that Morrisville Water & Light run less water through its turbines and leave more in the reservoir and river. They proposed the utility run the turbines more sparingly in the store-and-release model and closer to what is known as “run-of-river.” The utility could still generate electricity from water that flows naturally through the system, such as after big rainfalls, but could not release high volumes suddenly.

Instead of being able to draw the reservoir down 10 feet in the winter, regulators proposed a limit of 18 inches. And instead of a one-foot limit from June 1 to December 15, they proposed four inches.

Johnstone, a former secretary of the Agency of Natural Resources, understands why the utility’s former general manager, Craig Myotte, and its board of trustees chose to fight the new rules. In past interviews, Myotte estimated the restrictions would slash the dam’s power generation by about a third and would further put the utility at the mercy of price spikes.

Under the new operating requirements — which have yet to take effect while the relicensing process drags on — the dam would be a significant financial burden for ratepayers, Johnstone said.

The dam helps the utility keep rates lower by enabling it to purchase less power off the regional grid. But the new rules mean the cost of running the dam would exceed those savings by $236,000 annually, Johnstone said. The dam also needs about $1 million in repairs and $3 million for upgrades to comply with the new rules, Johnstone said.

Johnstone said he asked more than a dozen different dam operators if they would be interested in buying or running the hydro plant. Several expressed interest. “Then they review the water quality permit and they go, ‘Not on your life,’” he said.

Not Just Green River

One of those who passed on Johnstone’s offer was Arion Thiboumery, who co-owns and operates four hydroelectric dams in the state.

He agreed with Johnstone’s assessment that the new restrictions assure no one could run the hydro plant at Green River profitably. What he views as overregulation is an insidious problem affecting the industry statewide, Thiboumery said.

The impact on individual dams is often small, but it can add up.

“If the only thing the dam is being used for is to keep the state park, then I can’t ask ratepayers to pay for it.”

Scott Johnstone

Thiboumery cited the case of the Moretown No. 8 Dam on the Mad River, which he co-owns. When No. 8 was relicensed recently, regulators required that the facility release more water into a short section of the river called the bypass reach. That’s the stretch between the face of the dam and the point where water reenters the river after flowing through the turbines.

Instead of previous requirements to keep 25 cubic feet per second of water flowing through the 100-foot rocky bypass reach, the new permit requires the dam to allow 40 cubic feet per second. That lowers power generation by 2 to 5 percent, he said, for little if any benefit to fish. The reduction is relatively small, he said, because flows from the Mad River, which drains nearly 140 square miles of the Green Mountains, are usually sufficient.

But if similar reductions were imposed on all 102 hydroelectric dams in Vermont, Thiboumery said, “that adds up to be a real number.”

Calculating that real number is tricky. A 2017 analysis that South Burlington engineering firm VHB performed for the Vermont Independent Power Producers Association estimated that the new water quality requirements would likely decrease hydropower generated in Vermont by 5 to 25 percent.

“If all in-state existing hydrostations were to experience a reduction in energy generation in this predicted range, the impact to VT’s energy supply and renewable energy goals would be significant,” the report says.

That should give regulators pause, according to Peter Sterling, executive director of Renewable Energy Vermont.

“There really needs to be a high bar set for ANR to show a cause for reducing the power output from existing small-scale hydro dams,” he said.

Green Mountain Power is the largest owner of such facilities in the state. The company’s hydropower output has declined modestly as a result of new restrictions imposed during relicensing, said Josh Castonguay, chief innovation officer for the utility. Power generated by a GMP dam in Rutland decreased 1 percent, while power from dams in Newbury and Bolton declined 3 percent and 5 percent respectively, he said.

The utility operates 36 hydro dams in all, and some face rules that make it harder to generate at peak times, though it’s still possible, Castonguay said. But the utility has been growing its energy storage network in recent years, including by installing large batteries in homes. GMP can tap that stored power when wholesale prices spike, he said.

The electric department in Enosburg Falls, which serves about 1,800 customers in seven Franklin County towns, is seeking to relicense its century-old hydro plant on the Missisquoi River. Regulators’ demand for a 50 percent increase in bypass flows could reduce the dam’s generation by 15 to 20 percent, village manager John Dasaro said.

One utility is getting out of the hydro business altogether. The Washington Electric Cooperative, facing a 6 percent drop in production at its hydro facility on the Wrightsville Dam north of Montpelier, has decided to sell the operation.

The new rules halve the amount the utility could draw down the reservoir and double the amount of water it needs to keep in the North Branch below the dam. The facility was only “marginally cost-effective,” and the regulatory changes made it more problematic, said Louis Porter, the utility’s general manager. He is a former commissioner of the Department of Fish and Wildlife. The co-op chose not to fight with ANR over the tougher restrictions.

“We didn’t think the likelihood of success was high enough to warrant spending members’ money litigating it,” Porter said.

Last Stand

With its legal and legislative appeals nearly exhausted, Morrisville Water & Light is making a final bid for relief. Utility officials had previously threatened to tear down the dam, which would help restore the Green River to its natural state but would drain the reservoir. They have since backed off. Johnstone now argues that if the state’s operating restrictions force the utility to mothball the Green River plant, then the State of Vermont should own and maintain the dam thing.

“If the only thing the dam is being used for is to keep the state park, then I can’t ask ratepayers to pay for it,” Johnstone said.

A possible state takeover is the subject of a highly anticipated report due any day from the Agency of Natural Resources. The analysis is expected to outline the condition of the 78-year-old dam, long-term operating and maintenance costs, whether generating electricity from it still makes economic sense, and the cost of removal.

The state already owns and operates 14 dams, some of which require costly renovations in coming years. Safety upgrades to the Waterbury Dam, the state’s largest, are expected to run about $75 million, Secretary Moore said.

Preliminary findings from the consultant ANR hired to write the report confirm the Green River plant would be a money loser under the new restrictions and that upgrades wouldn’t help much, Moore said. In addition, the consultant found that if the state took ownership of the dam, it would cost $2 million to $16 million to operate and maintain over the next several years.

Vermont clearly has an interest in ensuring the dam remains in place and the popular state park is preserved, Moore said. But the state needs to be cautious about taking over a facility that needs millions of dollars in improvements, especially in a time of deep financial uncertainty.

“The reservoir, the camping, the habitat and all of those things have incredible value,” Moore said. “But we have to be able to have a conversation in the context of all the needs of our existing dam portfolio.”

Moore expects the report will set the stage for a difficult conversation with lawmakers in 2026.

“The case of this small dam on the Green River highlights part of our overall problem at almost every level.”

Sen. Richard Westman

Sen. Richard Westman (R-Lamoille) said he thinks the state ought to own the dam since it “put the squeeze” on the utility. The whole saga could have been avoided, he said, if regulators, advocacy groups and lawmakers stopped looking at the issue solely through the narrow lens of water quality.

Little if any consideration seems to have been given to the broad benefits of clean, inexpensive, local hydro power, especially for a fast-growing community such as Morrisville, he said.

“In many respects, the case of this small dam on the Green River highlights part of our overall problem at almost every level,” Westman said.

But Jon Groveman, the policy and water program director at VNRC, said dam owners should be held to standards that reflect the modern understanding of what makes healthy river systems and wildlife habitat. Instead of fighting the new rules, dragging their feet with endless regulatory filings or trying to get special permission to harm waterways, utilities such as Morrisville Water & Light would best serve their ratepayers by planning upgrades years in advance, Groveman said.

Unfortunately, he said, the utility was unprepared for the relicensing process and, when faced with tougher rules, blamed regulators and said, “Fix our problem by taking your foot off our neck.”

“Well, the foot is on your neck because you didn’t do the planning, and now you’re stuck in a shitty situation,” Groveman said. “We understand that, but the answer from our perspective isn’t just to sacrifice water quality and a healthy fish population.”

The original print version of this article was headlined “Power Drain | Hydropower facilities such as the one at Green River Reservoir are being pressed to make waterways healthier — which could mean less green energy”

This article appears in Aug 27 – Sep 2, 2025.