Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon is set in Michigan but begins with a reference to Durham: “The North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance agent promised to fly from Mercy to the other side of Lake Superior at three o’clock.”

You can find that oft-banned novel on the shelves of the Stanford L. Warren Library, a beloved branch in Durham’s Hayti neighborhood that reopened this past December after a three-year renovation. It is a library that contains many books you’re unlikely to find elsewhere.

Designed in 1940 by local architect Robert R. Markley, the building is a neoclassical jewel that’s just had its shine dull over the years. Its closure, for water damage in August 2021, was supposed to be temporary; upon meeting with community members for visioning sessions, however, the county allocated an additional $1.9 million to the library for more intensive renovations. The investment looks to have paid off: Airy new shelving, modern amenities, and structural reinforcement give the space a newly polished feel.

But while the branch may have a fresher feel, its legacy is still at the fore. And like many institutions, its history doubles as the story of the community around it—Hayti, Black Wall Street, Durham, and beyond.

Stanford L. Warren traces its origins to Dr. Aaron McDuffie Moore, one of North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company’s seven founders. The insurance company was founded in 1898; 15 years later, in 1913, Moore donated 799 books to the basement of White Rock Baptist Church. At the time, although Black Durhamites paid county taxes, they had no access to the public libraries that their taxes helped fund. Moore’s makeshift library changed this.

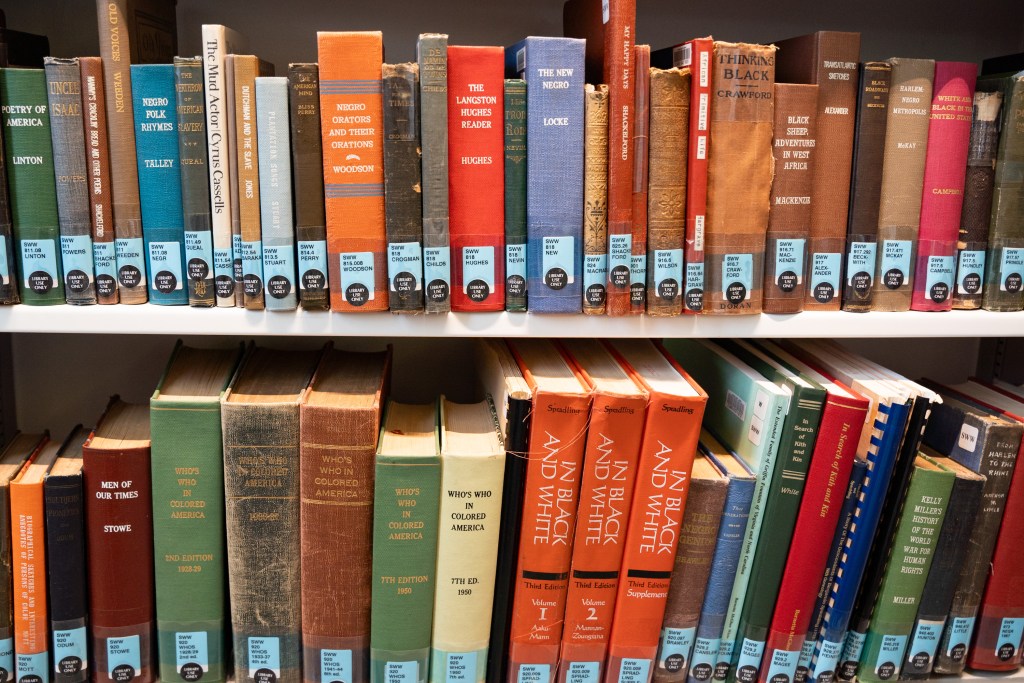

Today, those books—rare volumes on African-American culture and history— comprise the Selena Warren Wheeler Special Collection. The collection has evolved and seen a lot over 110-plus years: multiple moves, including to its current regal Fayetteville Street location; both world wars, urban renewal and the destruction of Hayti; the civil rights movement; integration into the country library system; more wars; the liquidation of NC Mutual; generations and generations of patrons.

The historic collection is one of the library’s distinguishing features and today helms a desk with a crisp-looking typewriter—details that give the space a distinct persona.

“The great thing about our library system is that it has its own uniqueness. North Regional is our rural library, and it has a uniqueness to it as well—you’ll see all the trees, the forestry. With this one, when you walk in, it feels like church,” says Larry Daniels, the branch manager at Stanford L. Warren. “We wanted to keep the historical significance of this library intact.”

Daniels, 39, is no stranger to Stanford L. Warren: He grew up in Hayti, a few streets from the library. Tall and energetic, Daniels loved basketball as a kid and wanted to be a sports journalist but—after interning in a Winston-Salem newsroom full of empty cubicles—decided librarianship was the more promising path.

He’s now been working at Durham Public Libraries for eight years. Journalism or librarianship—what he really loves, he emphasizes, is storytelling.

“When you come in the library and see books, it encourages people, like, ‘Hey, I can write a book, too,’” Daniels says.

The library’s upgrades include a 3-D printer, hall space for a community art gallery, and a small room for podcasting—places where people can experiment with storytelling.

“Now, there are different forms of storytelling—you can do it through music, you do it through podcasts,” Daniels continues. “What we’re interested in is allowing people to tell that story.”

It makes sense that Toni Morrison’s insurance man, searching for sovereignty and ascension in Song of Solomon, would be connected to Durham—a city that was, for so long, a wellspring of Black self-determination. NC Mutual Life Insurance anchored that autonomy.

This was expressed not just through the company’s success—it was the world’s largest Black-owned and -operated business for years—but by its investment in institutions for the Black community, including the library, Lincoln Hospital, and Mechanics & Farmers’ Bank, all located in or near Hayti. In 1916, Moore and his colleague John Merrick moved the church basement books to a more formalized service location on Fayetteville Street—the second library in the state available to Black North Carolinians.

Hayti’s Durham Colored Library, as the space was called, received some funding from the city and county. It was the surrounding community, though, that truly kept the doors open.

C. Eileen Watts Welch, Moore’s great-granddaughter, is on the board of the Durham Colored Library, which has evolved into a nonprofit. She describes Hayti as a “magnet, drawing people in who wanted a better life.”

Like Daniels, she grew up in the neighborhood.

“The levels of commitment in the families for the education of the children was very strong among the residents of Hayti,” says Watts Welch.

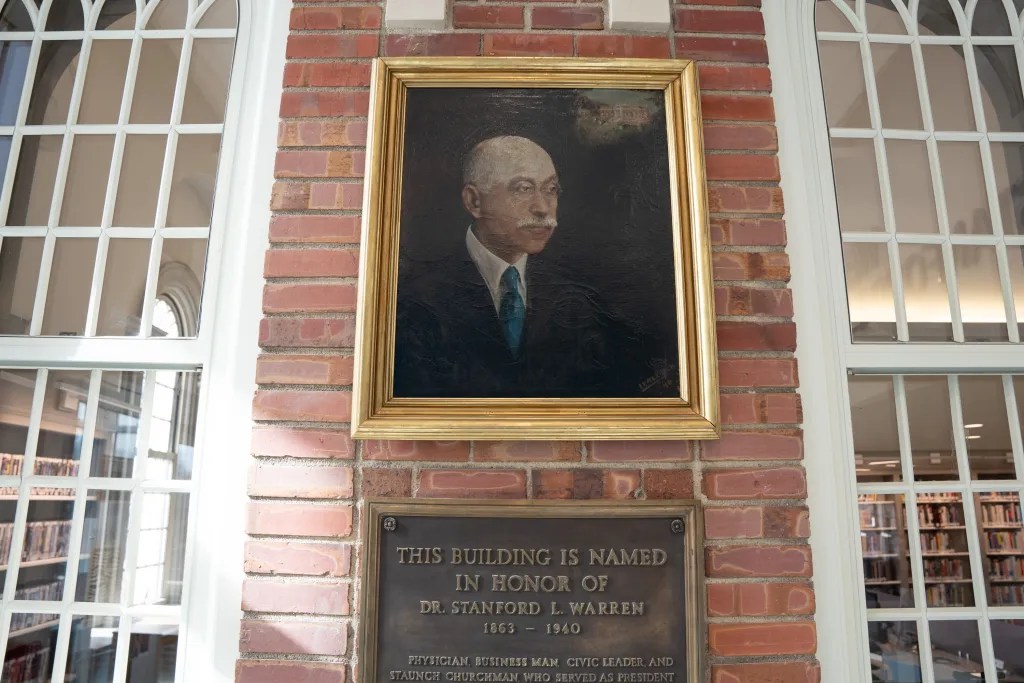

Over the next two decades, the library—largely thanks to its pioneering first librarian, Hattie B. Wooten—outgrew its small space. A $40,000 loan from NC Mutual alongside donations from community members—notably, library namesake Stanford L. Warren, whose daughter, Selena Warren Wheeler, became library director in 1934—was enough for a new building.

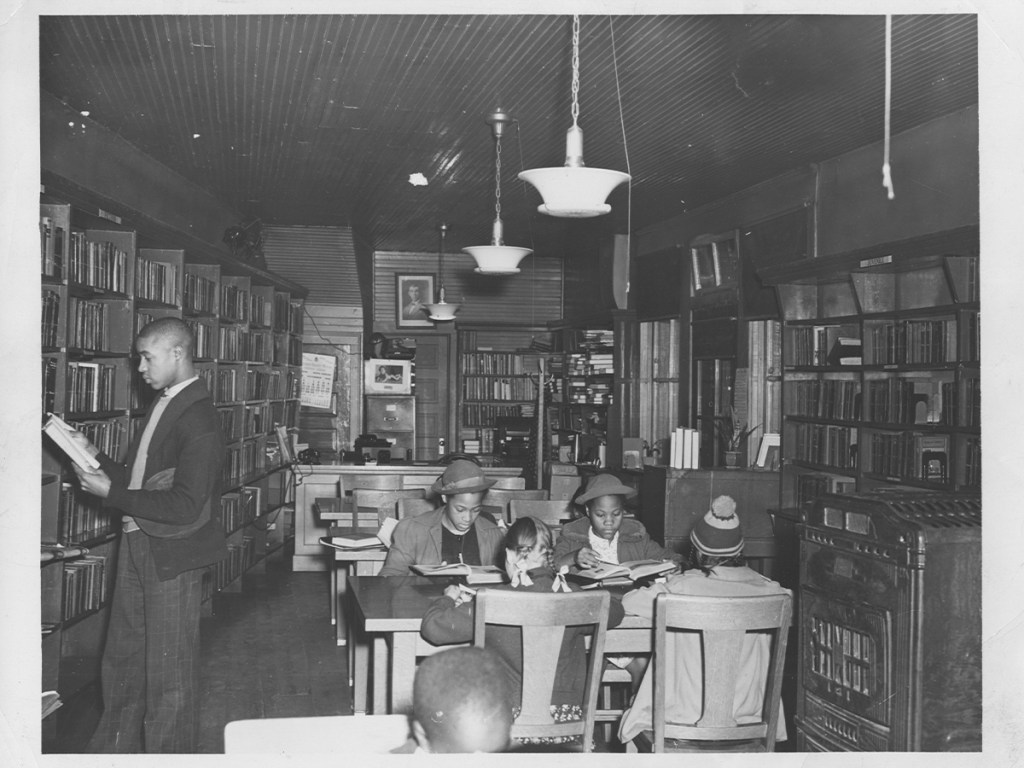

In January 1940, the Stanford L. Warren Library officially opened.

From the beginning, the space was about more than just books. It hosted regular community meetings and talks featuring prominent intellectuals like John Hope Franklin, Horace Mann Bond, and Pauli Murray (who grew up visiting Stanford L. Warren as a child). It expanded outreach, operating a bookmobile that traveled to rural parts of the county. Between 1954 and 1961 it opened three branches in Durham’s Black communities, one of which, the Bragtown branch, operates today. In 1966, these Black libraries merged into the county system.

But as the library saw steady engagement, the neighborhood around it was beginning to suffer. As manufacturing and the tobacco industry dropped off in the postwar years, the Durham City Council began to see the Hayti neighborhood as an obstacle to city growth.

The years-long construction of NC Highway 147, completed in 1970, tore up the neighborhood, displaced thousands of families, and drew a crevasse between downtown and Hayti. Residents were never compensated for the loss of their homes and businesses, and the neighborhood never fully recovered, a structural inequity reflected today in Hayti’s high rates of poverty and eviction.

“Many of that generation saw their world destroyed by the demolition that occurred in 1967—this was my junior year at Spelman,” Watts Welch says. “I remember that spring break coming home and seeing all of the cranes up in the air.”

These demolitions all came under the federal umbrella of urban renewal, though Watts Welch has another name for the program: “urban removal.”

“A lot of what I knew growing up is no longer there—and that was systemic,” Watts Welch says. “All of the planning had to do with taking properties where people were underserved and not able to defend themselves. It took away my grandparents’ house, my great-grandparents’ house, it took away my great-grandparents’ church.”

It is significant, then, that the Stanford L. Warren branch remained standing as the institutions around it have disappeared—alongside the community buildings demolished decades ago, NC Mutual Life was liquidated in 2022.

By the 1970s the building was worn down and the 1980 opening of the nearby Main branch led to a drop in circulation, leading to heightened concern about closure.

Nevertheless, Stanford L. Warren continued to serve an essential role. Carter Cue, the branch’s longtime adult services librarian, remembers the library as the heart of the neighborhood.

“We had a lot of latchkey kids,” Cue recalls. “Everybody had a working mother. There was nobody, no nanny, nobody to take the kids—so the library was that place, usually after school. If your parents are working, someone’s going to stay in this building until however late, until mom or someone gets off work.”

Decades later, Daniels affirms, Hayti still has that same tight-knit spirit. (It’s also a quality he embodies: When I pop by the library, one afternoon after Christmas, I spot him across the street with a black trash bag—he’s scooping up litter and chatting with neighbors.)

“It’s still the same as it was before when [my mother] was coming up, when I was coming up,” Daniels says “It’s an actual community. We still have Lincoln Community Health Center down the street, which is a recreation center, this library—you don’t see too many neighborhoods that have all these things.”

As Daniels tells it, the library’s approach is simply a reflection of the community it exists in.

“Everybody pretty much sticks together,” he continues. “What we do is we try to be a part of that—to exemplify what’s going on on the outside.”

In mid-December, community members filed into the new space and down the stairs, past a stairwell mural by local artist Gabriel Eng-Goetz, and into the library basement for an opening-day ceremony. Aside from a few small children, the crowd was mostly older Black Hayti residents—people who have seen that the library’s doors stayed open over the years.

“There were many, many people who expected that Stanford Warren would close,” Eddie Davis, a former teacher and Durham City Council member, told me. “But of course, it maintained its relevance and still does maintain that relevance.”

Watts Welch was on the morning’s program. Beyond her great-grandfather’s involvement in the library and in NC Mutual, he was also the first Black physician in Durham County, a legacy detailed in Blake Hill-Saya’s biography Aaron McDuffie Moore: An African American Physician, Educator, and Founder of Durham’s Black Wall Street.

“‘Give my people something to read,’” Watts Welch said, quoting her ancestor. “If you’re not educated, then you have a harder time with health care. An educated patient is going to have a better outcome.”

Watts Welch was also quick to thank the Durham County Board of Commissioners for its work with the library. The work is part of renewed attention, overdue many years, to Hayti: On December 16, Durham City Council approved $1.75 million in federal funds for the Hayti Promise Fayetteville Street Corridor Project. The money will go into revitalizing homes and commercial properties along Fayetteville.

Related stories

After the closing remarks, attendees filtered through the building, exploring changes. There were takeaway seed packets—poppies, peppermint, impatiens—a nod both to new beginnings and the library’s expanding natural footprint.

In addition to the plots of seasonal native wildflowers that already wrap around the building, Daniels has plans to transform the empty lot behind the library into a community garden and is working on securing grants for the project. (Library staff are also busy planning a related symposium, slated for March 30: The African American Legacy in Gardening and Horticulture).

There’s plenty of beauty inside the library, too. Cue has always prioritized visual art for the library, writing on its website that he has curated the space so that “those persons who might not experience art or a museum/art gallery in the formal sense” can be inspired.

Besides Eng-Goetz’s stairwell mural, which resembles stained glass and features motifs of Hayti, oil portraits of Moore, Merrick, and Warren are back up in the space—the first thing you see when you walk in.

Lighting is another change, too: the space is noticeably brighter. With a lighter paint job and stacks intentionally lowered, light from arched windows floods in.

“We want people to be able to tell,” Daniels says, “that the library is open.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Follow Culture Editor Sarah Edwards on Bluesky or email [email protected].