In an essay published in the New Yorker last August, “Why A.I. Isn’t Going to Make Art,” science fiction writer and technologist Ted Chiang offered what he admits is a useful generalization: “art is something that results from making a lot of choices.”

Jenn Karson‘s work bears that out, perhaps especially because her choices involve AI. She uses the software not to make images from an existing sea of content but to imagine more optimistic possibilities: how the tool can help us repair what’s damaged and generate something new.

Karson, an artist whose work centers on technology and the natural world, presents “The Generative Tree” at the Phoenix in Waterbury through March 15. The show includes more than 600 small prints, four extremely large ones, a sound component and an interactive piece, all made with help from the Plant Machine Design Group, the AI research team she has run since 2020 at the University of Vermont.

The project took shape after a 2021 outbreak of spongy moth caterpillars devastated trees in Karson’s Colchester neighborhood and, in particular, a beautiful 170-year-old oak on her property, which died from the infestation in 2023. She started investigating its leaves and the caterpillars, and the central question of her work became, she said, “What would a symbiotic relationship be between technology and the natural world?”

Fittingly, “The Generative Tree” unfolds through the gallery in nonlinear tendrils of inquiry. Along the left and right walls are 20 “Folios,” each a group of 32 unframed 4.8-inch-square images printed on canvas or matte paper and mounted to a white plastic grid.

On the “Phantom Silk Moth Folios” wall, photos document the caterpillars in action — dangling from their webs, massed on branches, cocooning — and the pains people took to try to hold back their siege by wrapping duct tape sticky-side-out around tree trunks.

Historical images present Étienne Trouvelot, a botanical illustrator and scientist who introduced and began breeding the moths in Massachusetts during the Civil War. He hoped to create a northern alternative to cotton, unavailable because it was produced using slave labor in the South. The project failed, and Trouvelot’s story became one of many cautionary tales of a poorly understood biotechnology causing widespread and irrevocable destruction.

Other prints come from the Damaged Leaf Dataset, a collection of more than 15,000 leaves that Karson and her students amassed and photographed during 2021 and 2022. Most of them belong to two sets of leaves produced by the same tree in the same season, which can happen when spring growth is damaged and the tree tries to heal itself.

The concept of healing is central to this work. Images in “The Generative Tree Folios” on the opposite wall include selections from the Plant Machine Group’s Athena Dataset, a collection of abstract geometric shapes — first made from cut paper — that they used to train their algorithm before AI tools were widely available. Later, they introduced the machine to the Damaged Leaf Dataset and to the Whole Leaf Dataset — a corresponding collection of undamaged leaves. As the machine learned the difference, the group asked it to create something in between, symbolically healing the leaves.

When this reviewer visited the exhibition, Camille Wodarz, a member of the Plant Machine Design Group and a senior computer science major at UVM, was installing an interactive piece that allows visitors to explore the machine-learning model for themselves by selecting images and choosing either to “heal the leaf” or “be the caterpillar.” The nearby “Generative Tree Folios” include prints of “healed” leaves, as well as images of the layers of data that the AI uses to create them.

Wodarz said how the AI makes its decisions is a bit of a mystery: “We don’t actually know how a computer ‘thinks.'”

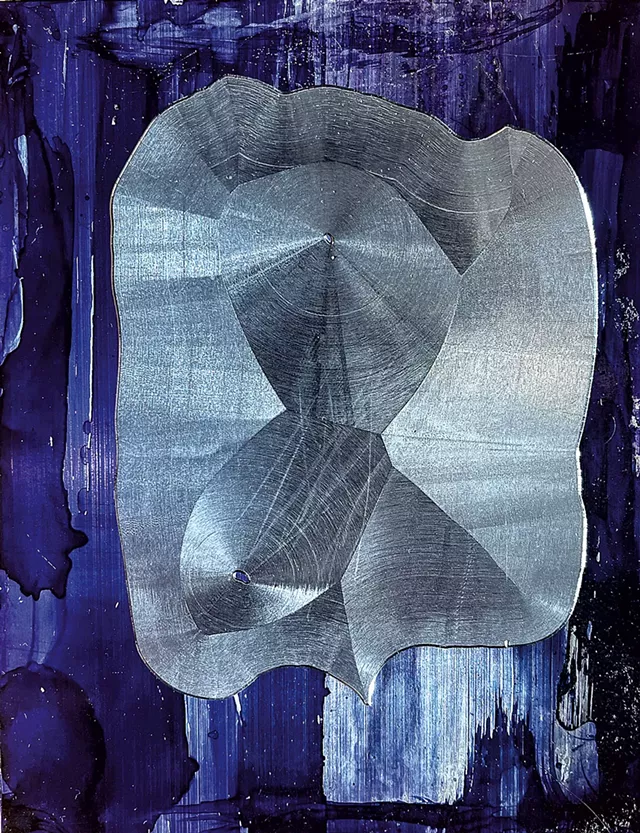

Karson also collaborated with machines on four massive 60-by-90-inch prints from the “Life Lines” series. After combining leaf outlines generated by the AI with her own, more traditional hand-drawn studies of leaf structures, Karson used a CNC router to engrave the drawings into aluminum blocks. The machine created its own lines where it dragged the drill bit from one area to another. Karson said she was fascinated by the design efficiencies involved, both the plant’s organic structural growth and the machine’s determination of the best path for etching.

“When I’m working with a technology,” Karson said, “I usually have to get to a point where I’m fighting with it — and I’m fighting with it because I want that artistic intention to happen.”

Through various iterations, Karson coaxed the machine into drawings that aligned with her intention. Alongside the large prints, she presents the original etched aluminum blocks, painted with violet machining ink — an aesthetic choice referencing the industrial process. The dark backgrounds enhance the luminescence of the etched surfaces, a reminder that even machine-aided processes can still spark magic.

The “Life Lines” prints were originally made on a smaller scale using India ink and pen plotters; these versions were digitally printed by Brooklyn Editions. From a distance, their overlapping black lines create planes that radiate into peaks and valleys. Each leaf seems to be made up of bent metal sections that meet in seams reminiscent of — but not exactly following — the veins of a real leaf. Their outlines veer off course, too, becoming blockier or wider or less symmetrical than one might expect. Looking shiny and clean, the leaves’ images read at this scale as monuments to their own imperfections, celebrating mutation.

The show also features a sound piece called “Psithuros,” a Greek word describing wind through oak leaves as Zeus’ whispers. It combines that sound with recordings Karson made of caterpillars and their frass dropping through the canopy, as well as fan noises from UVM’s advanced computing center — a reminder of the energy impact that all this computing has on the climate. The piece reflects a cycle of generation and decay that runs thematically through all of Karson’s work.

After installing “The Generative Tree,” Karson said, she was reminded of her reaction to her early AI-generated images. Seeing these hundreds of prints was like “looking through these flows of creation and decay — and sometimes not being able to tell the difference.”