This is an excerpt from the book The Magnificent Seven: College Basketball’s Blue Bloods, published this month by Lyons Press. Order a signed copy of the book and learn more about the authors’ event at Flyleaf Books in Chapel Hill on April 6.

As peculiar as it may seem now, for a time, the preeminent college basketball program in the Old North State reigned supreme in Raleigh. The N.C. State Wolfpack, under head coach Everett Case, helped build the Atlantic Coast Conference and constructed a program neighbors would seek to emulate.

UNC got so perturbed by Case, and losing to State, that it raided the St. John’s athletic department, poaching Frank McGuire. Duke opted for a resolution closer to home. They went after Case’s top assistant and recruiter, Victor Albert Bubas.

Although State had seen a relative dip in the latter part of the decade, Duke administrators believed, accurately as it turned out, that Bubas was the man who could elevate the program.

The first big break of the Bubas era came in 1959, when a big-time recruit from New York City decided he didn’t want to play in Chapel Hill.

Art Heyman initially had committed to play for McGuire and the Tar Heels, but during a recruiting visit, a fight ensued between Heyman’s stepfather and the UNC coach.

Inside the Carolina Inn—a place that still looks like Humphrey Bogart ought to be sitting at the bar sipping a scotch while holding a long, slender cigarette—Heyman’s stepfather made a comment to which McGuire didn’t take kindly.

“I had to step in between them,” Heyman told longtime Durham sportswriter Al Featherston years later.

“My stepfather called Carolina a basketball factory, and McGuire didn’t like that. They were about to start swinging at each other.”

The thing blew up, a verbal commitment was reneged upon, and Heyman ended up at Duke. The incident at the Carolina Inn served as an appropriate foreshadowing of Heyman’s proclivity for finding himself in the middle of fights.

Heyman was a brash New Yorker, unpopular with his own teammates and generally regarded as a hothead. His freshman coach, Bucky Waters, understood that Heyman had a temper and suspected that taunting and anti-Semitism would be directed at the Jewish player from the Big Apple.

The Duke and Carolina freshmen teams met three times in 1960, with Heyman’s squads winning each matchup. During one contest in Siler City, Waters even took extra precautionary measures.

“The team went on the bus, but I drove down with Art in a car,” Waters remembers. “I said, ‘I don’t know what’s coming, Art. But in any way they can they’re going to try to pull you down.’”

Which they did.

First with “very anti-Semitic, awful” taunts before some elbowing and physicality. Waters took a time-out in the opening minutes. And he used two others to try to quell the looming disaster.

As Waters recounts this story, his jaw tightens, and he mimics a grunting Heyman in response to the coach’s overtures.

“I knew what he wanted to do. He was a fighter,” says Waters. “I kept telling him, you can’t do that.”

Waters’s plan was to substitute Heyman out and have him glance up at the scoreboard (which favored Duke) as he walked by the Carolina bench. But it did not come off as planned. Carolina freshman Dieter Krause and Heyman got into it. Multiple accounts indicate that Krause threw the first shot, though the Tar Heel claimed self-defense.

“I remember a fist coming at me, and I instinctively ducked,” Krause recounted to ESPN more than 50 years later. “He missed in his effort to hit me with his right hand—and I instinctively counter-punched, and I connected with a punch to his face . . . and then total mayhem broke out.”

The two benches cleared; Blue Devil reserves surrounded Krause and delivered body blows with fists and feet as he resorted to the “embryonic position” to protect his head.

Waters, who boxed as a kid in New Jersey and later taught the sport at Duke, couldn’t keep his cool either.

“Instead of going out there and trying to bring order to the chaos, I went right to the Carolina bench, grabbed the opposing freshmen coach by the collar, and threw him on the press table. His butt was hitting all the switches, and horns were going off.”

Heyman, who averaged 30 points per game in that 1960 campaign, was melee-adjacent and bloodied, requiring five stitches. Krause, for his part, was ejected.

And if you can believe it, the Heyman-Krause fight was just the undercard.

The “Thrilla in Manila”—Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier’s third heavyweight title fight—might be the most celebrated fisticuffs in the history of mankind. But the biggest, baddest bout in the annals of Duke-UNC basketball had taken place 14 years earlier.

A year after that car ride to Siler City, on February 4, 1961, the freshmen teams—now without Heyman or Krause—tipped off at Duke Indoor Stadium as part of a doubleheader with the varsity teams.

Multiple fights broke out, and Carolina finished the game with only three players on the floor.

The freshmen were simply warming things up, as later that night, with Heyman once again on center stage, it got even messier.

“I knew what he wanted to do. He was a fighter. I kept telling him, you can’t do that.”

Now briefly, for contextual buildup, it’s worth noting that about a month earlier, Duke and Carolina met in Raleigh at the Dixie Classic.

The Dixie Classic was, for years, a heated affair that pitted Carolina’s Big Four—N.C. State, Duke, UNC, and Wake Forest—plus four other national notables, in a three-day tournament at Reynolds Coliseum in Raleigh.

A point-shaving scandal led to its demise, but not before the 1960 New Year’s Eve game between the Blue Devils and Tar Heels. That’s when UNC’s Doug Moe pestered, annoyed, and eventually limited Heyman—who had 11 very quick points—to just 16 by the end of the game.

Carolina won, 76–71. Legend has it that Heyman was furious, so much so that he tacked up a newspaper picture of Moe in his dorm room, psychologically readying himself for the next meeting.

By the time February rolled around, Heyman was ready. So, too, were his teammates, who had ticked off six straight wins and elevated themselves to fourth in the national polls, at the time Duke’s highest-ever ranking.

UNC, meanwhile, hadn’t been defeated since its Dixie Classic win against Duke, having posted 12 straight victories and garnering a number-five ranking in the polls.

The 1961 clash was the very first in a long line of meetings that saw both rivals ranked in the top five nationally.

Heyman performed extraordinarily well, despite some—how shall we say this?—uncustomary defensive approaches from Moe.

“He spit on me,” Heyman told the sportswriter Featherston. “Every time I took a shot, he spit on me. I told him I was not going to take that.”

Heyman and Moe squared off in the first half. No punches were thrown as the tension kept mounting.

Upon returning to the floor, Heyman got a tap on his bum from a Carolina cheerleader, and the volatile 6’5” Blue Devil turned around and shoved that cheerleader to the floor. Assault charges followed days later, brought by a local attorney who happened to have graduated from UNC Law School.

Inside of a packed Durham courtroom, the case against Heyman—who had tossed the young cheerleader named Albert Roper—was promptly dismissed.

Back to the game in progress, second-half tensions were now truly simmering.

Heyman hit two free throws with 15 seconds to play, and Duke led by five. Larry Brown—the future coach—then collected the inbounds pass and drove to the hoop. Heyman fouled him, thinking that a whistle would allow for a substitution and a well-deserved ovation.

“Every time I took a shot, he spit on me. I told him I was not going to take that.”

Brown had other thoughts, however. He took exception to the foul committed by his long-ago friend from Long Island and sharply threw the ball at Heyman. And then he swung at him.

The disaster in Durham was fully underway.

Heyman and Brown locked up, and the tussle escalated when Tar Heel reserve Donnie Walsh—yes, the future longtime NBA executive— attacked Heyman from behind. ACC Commissioner Bob Weaver would later describe Walsh’s actions as “hit-and-run tactics.”

Fans poured onto the floor, and the cops waded into the fray. It required nearly a dozen officers to restore some level of order. Black-and-white footage of the brawl is pretty wild.

Inexplicably, Brown was not ejected. Heyman, who scored a game-high 36, was chucked.

Duke won 81–77, and the greatest rivalry in college basketball was born.

The early 1960s were a period of growth for the Blue Devils. Following the 1961 campaign that sputtered out, Heyman was joined in the backcourt by another New York guard (by way of Lexington, Kentucky) named Jeff Mullins.

“I was recruited by Kentucky,” Mullins, who moved from the Big Apple to Lexington when he was in high school, recalls.

“But I had reservations about playing for Adolph Rupp. My reasons were that I was definitely a late bloomer. I had a great high-school coach, but my three years were really development years. And to be honest with you, I didn’t think when I graduated that I was anywhere near a finished product.”

Kentucky pushed, and Rupp enlisted the governor, Democrat Bert Combs, to help close the deal.

“I went to see the governor twice. And he very, very nicely stated that if I plan on staying in Kentucky, I definitely ought to go to the university. He was very nice about it.”

Mullins opted for the dimmer lights of Durham, where he would team with the impulsive Heyman and play for the not-yet-established 33-year-old Bubas.

“He was very competitive. He had tremendous character and integrity. He was a true gentleman, but he had a burning desire to win,” says Mullins. He also depicted Bubas as a tremendously organized coach who ran no-nonsense practices and rarely, if ever, raised his voice.

The Heyman-Mullins tandem each eclipsed an average of 20 points per contest as Duke finished second in the ACC. Many observers figured that the 1962 season would provide a conference tournament final rematch between Wake and Duke.

The basketball gods had other plans, however. Duke was upset in the conference tournament by an inferior Clemson team that it had twice defeated in the regular season, dashing any dreams of a March Dance.

Instead, the Demon Deacons rolled Clemson a day later, and then marched to the only Final Four in school history.

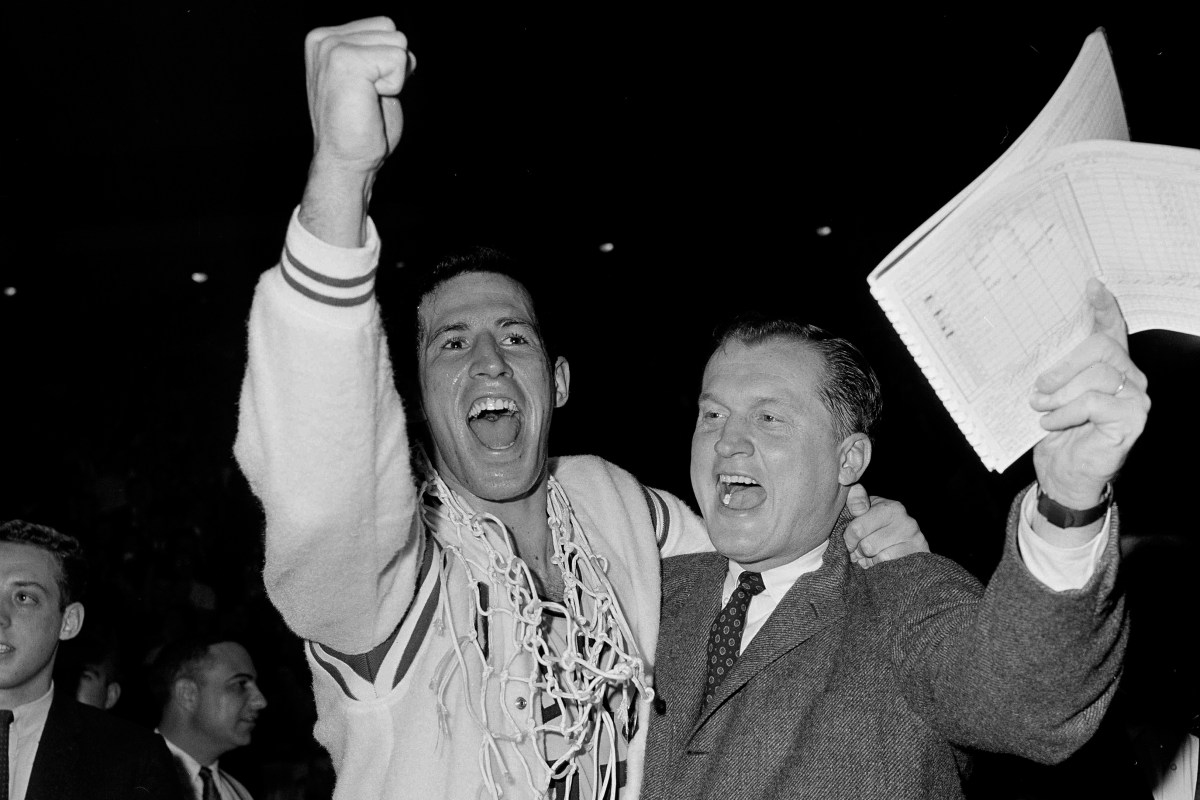

Heyman and Mullins spent one more season together, and the 1963 campaign was their best. The Blue Devils won every one of their 14 ACC games, defeating UNC twice, and exacted some long-overdue revenge against Wake in the league’s title game, after which Heyman earned MVP honors.

Duke was back in the NCAAs following a two-year hiatus, and Bubas’s team proceeded to defeat New York University and St. Joseph’s to earn the first of many Final Four berths for Duke.

At Freedom Hall in late March, the Blue Devils were blown out by a Loyola of Chicago team that would go on to defeat Cincinnati for the title the next night.

It wasn’t the culmination per se, but it was pretty darn close. Heyman was named the Associated Press National Player of the Year–though he had to wait 27 years for his jersey to be retired.

A footnote to that 1963 season that is just kind of wild and bespeaks, possibly, the Duke-UNC dynamic.

Heyman was arrested that year in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, charged with transporting an underage woman across state lines for immoral purposes. It’s possible that Heyman tipped his hand when he attempted to check into a motel under the alias “Mr. and Mrs. Oscar Robertson.”

Who made what calls to get the charges dropped remains unclear, at least publicly.

What is clearer was Heyman’s position on the matter. Up until his death in 2012, the Blue Devils legend maintained his belief that private detectives were tracking him and exposed the tryst. Heyman said that after the brawl with Brown and Walsh two years earlier, private eyes tailed him on occasion; and he held that these private eyes had been hired by UNC supporters.

To comment on this story, email [email protected].