This “Life Stories” profile is part of a collection of articles remembering Vermonters who died in 2025.

The man everyone knew as “Highway” was not tall, that much is true. The precise distance from Highway’s heels to his head remains a matter of perspective, however. “Probably about five foot,” his ex-wife, Sherry Dupee, estimated. His sister Noel Weeks pegged Highway at five foot, five inches, with the qualifier that, for a time, he was as wide as he was short. “Maybe, like, five-two,” old friend Leo Ashby said. In a 2001 profile, Seven Days copublisher Paula Routly simply described Highway as “short.”

A quick check of Highway’s driver’s license might put the matter to rest — except Burlington’s most beloved roadie apparently never had one during his 63 years of life.

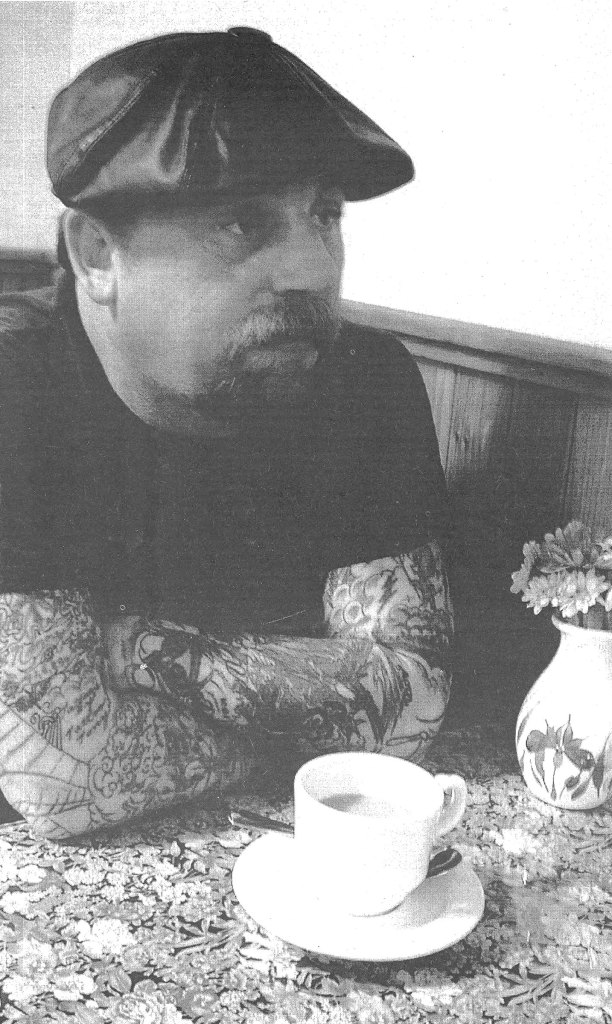

Maybe it’s crass to belabor a dead man’s stubby stature. But Highway was a man of his words, and in order to hear them, to really appreciate their wit, their force, their undeniable tallness, you first have to try to see him — there on some downtown corner, probably Church Street, or in City Hall Park, taking into confidence one of the wayward teens who called him “dad” or straightening out someone who was up to something crooked. Neckless, mustachioed, wearing his leather jacket, jeans and a beret, with his ears pierced and every body part but his face tattooed, speaking in a roughed-up New Jersey accent:

“It’s either my way or the highway. And since I’m Highway, it’s my way.”

“I have either been there, done that, seen it, been part of it, heard about it or been connected to participants of whatever it was.”

“Sometimes I think two kids should kick the shit out of each other — just once, to get it over with, get it out of their system, awright?”

Life could seem bigger around Highway, a legendary figure in Burlington who trafficked in tales of adventure and street wisdom gleaned from his life on the road. He cultivated that romantic mystique even as he was too earnest to adopt the truly detached attitude of a drifter. Instead, Highway appointed himself the watchman over Church Street for much of the ’90s and 2000s. He took a particular interest in the well-being of young people whom others dismissed as delinquents. He handed them condoms, discouraged the use of hard drugs and dispensed practical, nonjudgmental advice. He once took two quarreling teens to the mall cafeteria and wouldn’t let them leave the table until they shook hands; another time, he watched out for cops as two other teens settled a disagreement by trading blows atop a downtown parking garage.

So Highway told fish tales and offered extrajudicial solutions, but both were ways of seeking and showing love, according to those who knew him best.

“He was like a human version of a pit bull,” Ashby said. “If you fed him and treated him right, he was good to you. But if you crossed him, you know…”

Most people didn’t know Highway’s real name: Todd Gerard Sica. He was born in New Jersey in 1961, the eldest of his mother’s eight children. In childhood he survived a life-threatening condition called hydrocephalus, in which spinal fluid built up in his brain. Most children in the ’60s with the diagnosis did not survive, but Sica’s mother “hunted down doctors” who could treat her son with emerging techniques, Weeks said. For the rest of his life, he lived with implanted surgical shunts that drained the excess fluid from his brain.

His mother moved the family to Vermont in 1977 following a vacation on which she found herself enchanted. Highway split his time between his mother’s house in Vermont and his father’s place out of state. He began picking up odd jobs, a lifestyle he’d never give up. Highway worked in concert security, as a highway flagger and as a stagehand at the Flynn.

His work as a roadie for rock bands provided the fodder for many of his seemingly far-fetched stories. Highway talked of palling around with megastars when he went on tour with the likes of Bon Jovi, Bruce Springsteen, Lynyrd Skynyrd and Phish in the ’80s and ’90s.

Weeks politely dubbed her older brother a “storyteller” before shedding the euphemism for affectionate straight talk. “I say storyteller to be kind,” she said, “but he was a bullshit artist.”

“If even a small fraction of his stories were true, he lived an amazing life.”

Noel Weeks

And yet, Highway made Weeks wonder. He boasted to his family about knowing Steven Tyler of Aerosmith. They rolled their eyes, until Highway took his mother backstage during a show to meet the band, “and they’re like, ‘Hey, Highway!’” Weeks recalled.

Then there was the time Highway showed up on Sally Jessy Raphael’s daytime talk show, being interviewed in the audience about his tattoos. No denying that one — he was right there on television.

“If even a small fraction of his stories were true, he lived an amazing life,” Weeks said.

Highway’s onetime girlfriend and longtime friend Susan Chadwick counts herself a believer. “A lot of people think it was just storytelling, but I know it was true,” she said.

Yet the riddle of Highway goes all the way down to the nickname itself, the one he wanted everyone to use, all of the time.

“He told me that someone called him that because he’s always traveling, always on the highway,” Chadwick said.

And here’s Dupee, Highway’s partner for 16 years: “I do know how he got that one. Him and another guy were traveling to a gig. I don’t remember what state it was in.” The two men made a $100 bet, she said. “Whoever got there first got the money.”

Sica’s coworker went to the airport and took a plane. “Highway decided he was going to stick his thumb out and hitchhike to wherever they were going,” Dupee said. Sica got there first, and their manager at the jobsite, a guy named Frank, dubbed him Highway.

Both women met him at his favorite haunt, the streets of downtown Burlington. Chadwick said she and Highway watched over the loitering teens together, taking them under their wings, before their short-lived romantic connection became a decades-long friendship.

For Dupee, Highway began as a story told by her youngest son, a rowdy teen who “didn’t listen for beans” and was one of the street kids Highway adopted. “My youngest son always said, ‘If you ever have trouble with me and you can’t get me to listen, go find Highway.’”

So one night, Dupee said, she did. Then she brought Highway home to talk to her son. Eventually the teenager went to bed; Highway and Dupee stayed up until 6 a.m. talking on her living room floor.

They married on the summer solstice of 2003 on the steps of city hall, during a farmers market. Highway’s friend’s bull mastiff served as ring bearer, and Dupee’s friend’s pug served as flower girl. Their wedding photos included strangers who were shopping for vegetables.

The couple moved to Florida, to both Carolinas, to Las Vegas, to Hawaii. “About every year, he was like, I’m so sick of this. I got to get out of here. I’m never coming back to Vermont,” she said, “and two months later we were back in Vermont.”

Dupee figured Highway related so well to teens who today might be called “at-risk youths” because he could relate to their restlessness and the longing to belong that tends to lie beneath.

“He craved family, and he craved belonging,” his sister Weeks said.

Filling that need eluded him in some ways. Highway and Dupee split in 2019 when, according to Dupee, her husband was struggling. “He was having some trouble with the shunt that was in his head, and he was acting really weird,” she said. “Things went from bad to worse. I walked out the door.”

“Feeling kinda crappy, The person I love more than anyone has left my life,” Highway wrote on his Facebook page around that time. “This is an excruitiatly [sic] painful way to learn a lesson.”

Highway’s health continued to decline. He developed rectal cancer but was careful about how much he information shared. He moved into an apartment in Decker Towers, where his friend Chadwick lived, and found an audience for his stories at the bus stop/smoking shelter out front.

“He was just making the best out of what he had,” Ashby said. “He accepted his fate.”

Weeks was surprised when death struck her older brother. “Our last conversation, he had told me his cancer was in remission,” she said.

Highway was found in his apartment, face down on the floor, Weeks said. The official cause of death was listed as stage III cancer. Weeks suspects something swifter took his life, perhaps a heart attack or stroke. Because officials had ruled out foul play, his family opted not to ask for an autopsy.

We’ll never know for certain what killed Highway. But the truth was never really the point.

This article appears in Dec 24 2025 – Jan 6 2026.