Books

North Shore’s Chris Van Allsburg talks North Pole magic, Tom Hanks, RISD — and how a Boston editor convinced him to become a children’s book author.

When I was in third grade, a boy in my class announced one recess he heard Santa wasn’t real.

We scoffed, but he sounded certain. “My mom told me,” he proclaimed from atop the slide.

Because he had this on authority from a real grown-up, something unsettling rippled through me that day on the playground.

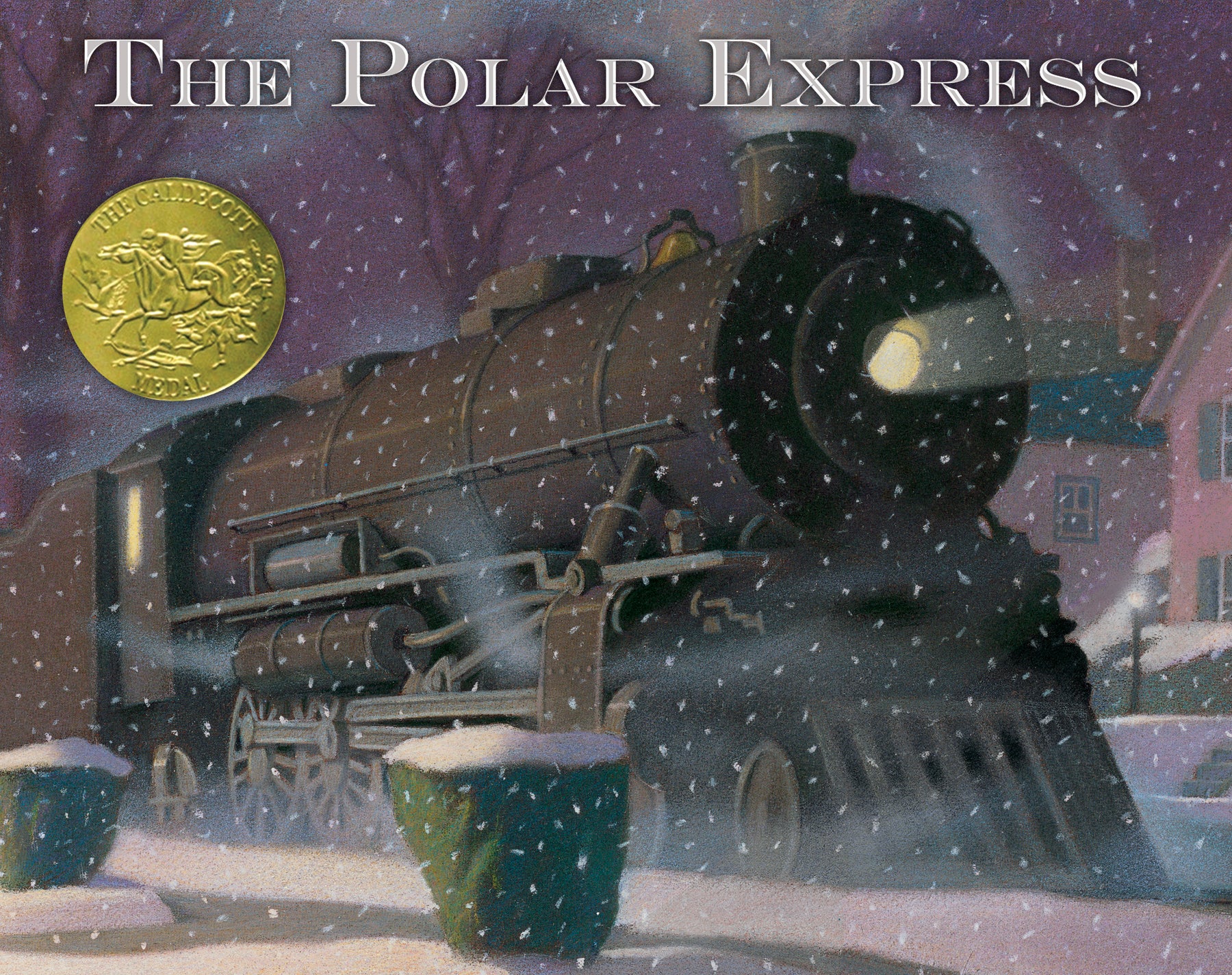

I’m not sure if our teacher knew we were teetering on the edge of belief when she read Chris Van Allsburg’s “The Polar Express” that week, but it pulled me back from the slippery brink.

Nothing about this book looked like a sugar-coated fairytale. These were dark, serious images that demanded attention; the story gave a thrill of suspense, almost unease.

When my teacher rang a silver bell at the end (just like the silver bell Santa gives the boy in the book!) goosebumps ran down my 8-year-old arms. My faith in flying reindeer restored.

The North Shore’s Van Allsburg has kept North Pole magic alive for generations now.

The Beverly children’s book legend’s “The Polar Express” — his ’85 bestseller and ’86 Caldecott Medal winner — turns 40 this Christmas.

“It makes me feel old. But to have a book in print for 40 years, and see it as popular as it was the first year — that’s a gratifying feeling,” Van Allsburg, 76, told me in a phone interview from his Beverly home this week.

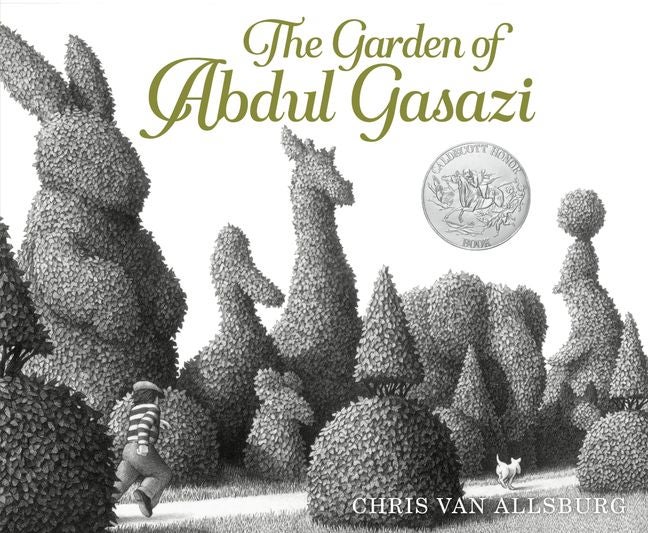

From his 1979 debut “The Garden of Abdul Gasazi” to 1986’s eerie “The Stranger” to 1992’s eerier “The Widow’s Broom” there is absolutely nothing about Van Allsburg’s work that screams children’s storytime.

His illustrations are dark — literally and figuratively. Something haunting lingers in the images. Stories might have no solid conclusion. There are surrealist “Twilight Zone” undertones, notably in books like “Jumanji” (1981) or “The Wretched Stone” (1991)

Peak Van Allsburg is hands-down “The Mysteries of Harris Burdick” (1984) — 14 black and white illustrations with simply a title and caption. The reader is asked to not only come up with her own conclusion, but invent the story.

Van Allsburg is probably one reason I now love mysteries and thrillers.

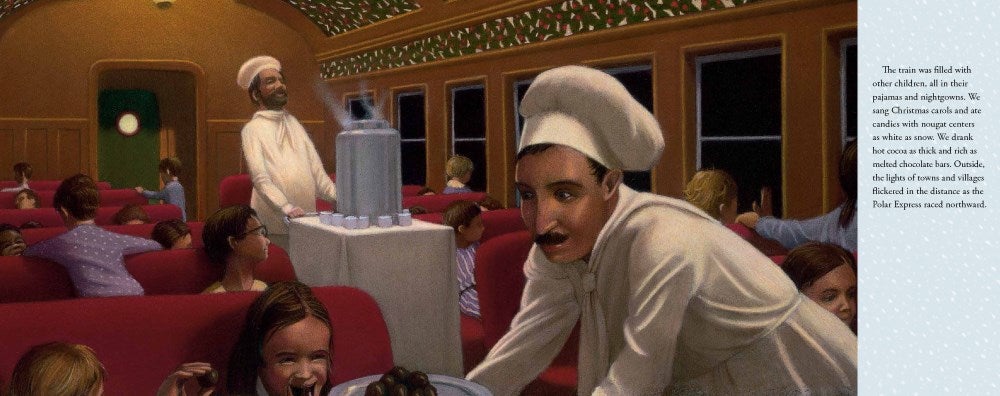

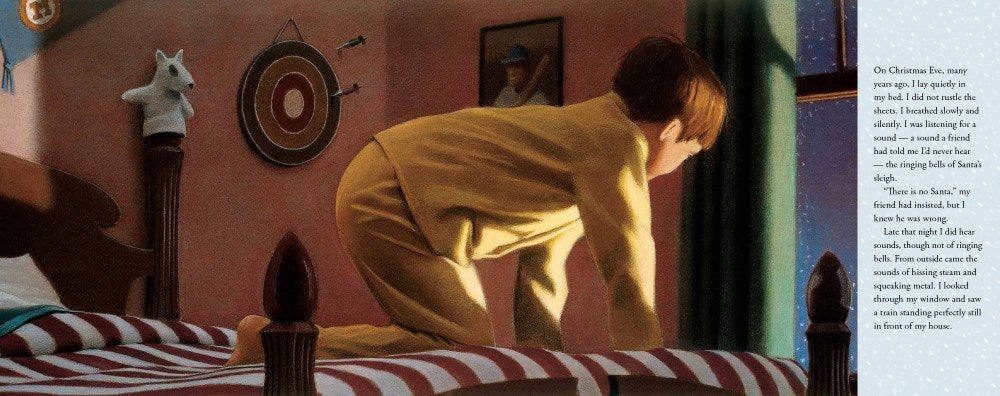

“Polar Express” — his tale about a boy who boards a mysterious steam engine train in the dead of night, and is gifted a single bell from Santa, then loses it on the ride home — also has all the Van Allsburg hallmarks.

“I started writing a story, a somewhat autobiographical coming-of-age story. Those are usually associated with teens. But when you’re 8, 9, 10 — the coming-of-age event is no longer believing in reindeer flight,” Van Allsburg told me. “I remember being on that cusp, and clinging to belief.”

And it turns out, he tells me, that if not for a Boston’s children’s book editor willing to take a risk on black and white illustrations and stories with no clear ending, his books might not exist at all.

Today he’s the author 0f 18 books, a few of which have seen star-studded adaptations. The 2004 Tom Hanks-produced adaptation of “The Polar Express,” is now streaming on Hulu and Disney+.

A 1995 “Jumanji” adaptation starred Robin Williams. “Zathura,” was adapted as “Zathura: A Space Adventure” in ’05 starring John Hutcherson (“The Hunger Games”) Kristen Stewart, Dax Shepard, and Tim Robbins.

More recent “Jumanji” films starred Jack Black, Kevin Hart and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson. There’s a slated 2026 “Jumanji” adaptation starring Danny DeVito and Nick Jonas, per Hollywood Reporter.

Born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Van Allsburg earned his masters in sculpture from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1975. He lived for years in Providence with his wife, Lisa, an elementary school art teacher. The couple has lived in Beverly for some 16 years. They have two grown kids, two grandkids, and a schnauzer named Smudge.

“We’re happy in New England. But we still pronounce our r’s,” he says with a laugh.

I called the two-time Caldecott Medal winner at his Beverly home for a wide-ranging interview. We talked about North Pole magic, Tom Hanks, and how a cold Providence studio led him to a Boston editor, and more.

Boston.com: So you graduated with a master’s in sculpture from RISD in ’75. You never had any formal training in illustration?

Van Allsburg: Zero. The only drawing I did for my college education was drawing sketches of things I was going to sculpt. I knew nothing about picture-making. And because my experience with image-making was with pencil or charcoal, my first children’s book was done in carbon pencil.

That was 1979’s “The Garden of Abdul Gasazi,” which won a Caldecott honor.

I remember reading a couple reviews that praised it for the intelligent choice of doing it in black-and-white, which enhanced the mystery of the story. I was happy to have the praise, but I didn’t make a choice — that was the only way I could do it. [laughs]

[laughs] So how did you go from sculpting in bronze and wood in a Providence studio to writing an acclaimed kids book?

The studio in Providence was cold. When winter came, the landlord was turning off the heat around 5 p.m. It was too cold to work. So I got some pencil and paper and started drawing pictures — narrative pictures with people in them. There seemed to be stories behind them.

You drew a man in a tuxedo, biting into a dinner plate, with a woman next to him with a startled expression: “The Impatient Dinner Guest.” That feels lifted from “Harris Burdick.”

You’ve done some deep research.

[laughs] You actually told me that once, years ago.

[laughs] Yes, “The Impatient Dinner Guest” was a prime example of the kind of drawings I was making then. The narrative quality led my wife to suggest I do children’s book illustration. She taught elementary school art in Providence, and brought home some books.

I wasn’t inspired by them, and I wasn’t in agreement with her assessment that I had any place in children’s book illustration. What I was doing wasn’t like anything I saw in those books.

Right.

So I was still making sculptures. But my wife thought, as a side hobby, I could do children’s book illustration. She took the work around to a few publishers in Boston and New York, and returned with a few [written] manuscripts [that needed illustrations.]

I don’t want to be critical of them, because I know they have an audience but — and it’s an odd criticism to make of a children’s book — they were all quite childish.

[laughs] Makes sense.

[laughs] Something like a little rabbit going to school for the first day and a lesson about sharing your carrots. I couldn’t picture myself drawing rabbits with backpacks. So I passed.

But one editor in Boston responded very positively to my black-and-white drawings. He called me up one day and said, “If you want to do the kind of drawings you’re doing, you’re going to have to write [your own] manuscripts.”

You said that was Walter Lorraine. He’s another RISD alum.

Walter Lorraine was my editor for my first dozen books at Houghton Mifflin. He was a legend in the field. There weren’t many men in children’s publishing. My relationship with him was very productive because he left me pretty much alone. His philosophy — which is pretty unusual in publishing — was that the publisher’s role was to facilitate the artist’s effort, that the editor’s role was to identify exactly what the artist was trying to make, and let them make it.

That’s ideal.

I told him, “This is just a little side gig for me. I have no intention of becoming a children’s author.” He said, “Well, you should think about it. I think you could do something original.”

I was drawing pictures of topiary gardens — spooky places. I imagined a dog running through it. That enlivened the image. I imagined a boy chasing the dog. I asked myself: whose garden is it? Why was the boy chasing the dog? Where was the dog going?

After ruminating a few days, I came up with a story. When I took it up to Boston, Walter was happy with what he saw. The story never answered a question— just posed it. But he said, “I’m not bothered by that.”

Also, black-and-white drawings were not popular at the time — still aren’t. But he said, “We’re gonna publish this.” I thought, “Great,” and sort of checked out of the whole thing, went back to sculpting.

But then it was reviewed in the New York Times Sunday Book Review — I was just bewildered. [laughs] It won a Caldecott Honor. I was forced, at that point, to consider this opportunity.

How did the story of “The Polar Express” (1985) come to you?

An image kept visiting me in waking reverie: a steam train standing perfectly still in a woodland setting in wintertime. The car lights were visible. I was at a distance from it. I imagined myself walking through the snow and approaching this train. Why was it standing still? Who was on it? Who was operating it? What was its destination?

I thought, “Well, if I was a kid, and it was winter, I might ask it to take me to the North Pole.”

And what did you think of the 2004 film adaptation?

There’s a central melancholy quality to the film which I thought was faithful to the book. The problem with the film — I’m trying to search for the right word without sounding ungrateful — there was some criticism about the motion-capture technology.

The uncanny valley.

You cannot read about the uncanny valley without seeing a reference to “The Polar Express.” [laughs] It was the first time [that technology] was used in a feature-length film — certainly the most ambitious application of it. I think it was successful, aside from the children’s faces. Movement was good.

I’ve seen the movie quite a few times because my grandson likes it. I still haven’t gotten used to the spooky-looking kids, but overall, there’s a mood to the piece that I respond to positively. It’s kind of dark, but in a way uplifting.

Like a lot of your works, actually. And how did that movie come about? Tom Hanks starred and produced.

I can’t remember what year it was, but somebody told me they were watching late-night TV, maybe Letterman, and Tom Hanks was a guest. They asked him how he was celebrating Christmas, and he said, “Well, there’s this great book, ‘The Polar Express.’ My kids love it. I went out and got a train and set it up around the tree.”

Some time passed, I got a call, it might’ve been from my publisher. They said they’d had an inquiry from Playtone — Tom Hanks’s production company.

Tom sent me a fax — that’s how long ago this was — and we had a conversation about what he envisioned. They had discussions with the director, Bob Zemeckis, about his desire to use this new technology.

When everything was set up, I went out to California and met with everybody. I was a little skeptical that it was possible to make a feature-length film [about a 32 page] book.

I was pitching ideas about an origin story — trying to find out where the conductor came from. There was a point in the meeting where they said, “You know, Chris, you sound like a producer.” And it was not a compliment. [laughs]

Do you hear from kids about “Polar Express” this time of year?

Not so much about “Polar Express.” Kids are more interested in “The Stranger” or “Wreck of the Zephyr,” which has a mysterious ending. They want to know if they’ve figured it out. Sometimes I write back and say, “What do you think?”

Lauren Daley is a freelance culture writer. She can be reached at [email protected]. She tweets @laurendaley1, and Instagrams at @laurendaley1. Read more stories on Facebook here.