This is an excerpt from the book Custom Made Woman: A Life in Traditional Music, written by Alice Gerrard and published this month by UNC Press. The release event is on December 2 at Cat’s Cradle.

That’s for me to know and you to find out. —Hazel Dickens (when somebody would ask her age)

We used to be a family in our little cabin home

Whose windows they are broken and whose chimney’s dark and cold

But jobs were hard to find back then, it wasn’t easy to survive

So one by one we all left home to change our way of life. . . .

You gave me a song of a place that I call home

A song of now, a song of then, a song of yet to come.—“You Gave Me a Song” (words and music by Alice Gerrard)

There are a lot of memories that are pretty foggy, but I remember one in particular, when Jeremy said to me in early 1953, “There is this little skinny girl with a great big voice that you’ve got to meet.” Meet her I did, and we shared a musical partnership for many years.

Hazel Dickens was born in the coal mining area around Mercer County, West Virginia, in 1925, and had moved, gradually, along with much of her family, to Baltimore after World War II. Like many other Southerners, they hoped to find better work and a better life, and Hazel worked as a waitress and in factories like Continental Can and Dixie Cup.

She was shy and very self-conscious, aware of her lack of formal education, her accent, clothing, and many of the cultural differences that set her apart; she told me about the time someone made fun of her for calling Pepsi and Coke “pop” instead of “soda”—just one of a thousand cuts. Country music is full of songs about leaving the country for the city, hard times in the city, not finding a better life there, longing for home, disillusion, and breakup of families. These songs are staples of country music—“Streets of Baltimore” and “Detroit City” are two that come to mind. I wrote on the subject in my song “Sky over Michigan”:

I traded quiet country evenings for bright city sounds

Hard work and worry for hard work and doubt

And this dirty old factory job in Detroit town is a far cry

From a glass slipper & a satin ball gown

By coincidence, Hazel met Mike Seeger when he was working at a tuberculosis sanitarium outside of Baltimore, where one of her brothers was a patient. Through Mike she met other people, including Alyse Taubman, a kind-of-lefty bohemian social worker and music lover who took Hazel under her wing, encouraging her to believe in herself. She became a strong mentor and important friend to Hazel. I believe that I first met Hazel at one of many music parties at Alyse’s apartment in Baltimore.

Hazel had a wicked sense of humor and a twinkle in her eye.

She didn’t immediately trust anyone and liked keeping her “business” to herself. Country smart, she’d grown up hard and poor. Her father, H. N. (Hillary) Dickens was a powerful singer and banjo player but gave the banjo up when he joined the Primitive Baptist church in his early twenties. (Later, Mike Seeger recorded Hillary’s singing and banjo playing for the album Old-Time Tunes of the South on Folkways Records.) Hazel’s mother was a quiet, sweet woman, very deferential to her husband, and not a singer or musician that I can remember, although most of Hazel’s eleven siblings sang and played.

She had a singing voice that could nail to you a wall, the kind of voice that embodied the “high lonesome sound” to me. She played guitar and bass well enough to occasionally fill in with some local bluegrass band at some random bar gig. But it was that voice! Edgy, piercing, high, lonesome, cutting, and raw: Hers was an oasis in the desert of pretty, sweet voices emerging during the folk revival of the late 1950s and early 1960s.

I was in awe of Hazel’s singing, trying to grasp hold of its mysterious power for a long time, listening to her, looking to her as a mentor, learning from her. She was older, generally streetwise and street-smart, and in this world of music and bridging cultures, with her innately suspicious and private nature, she knew what was best. We gradually became friends, and when at some point, someone at some music party suggested we try singing together, it seemed like a good idea. It was always informal, and we never considered that we might take it further.

Our recording career started with another party, as I remember, where Peter Siegel was present. He was a young music enthusiast from New York who was heavily involved in the New York City folk scene as both musician and engineer during the early 1960s. Both Peter’s and my memories are a bit hazy about the circumstances, but between the two of us, we remember that he and his friend David Grisman, both in their late teens, had come down to DC from New York to attend a bluegrass festival that got rained out. Somehow, Peter and David ended up at a music party at my cousin’s house on the edge of Georgetown.

Hazel and I were there, and of course we were singing. I checked the notes to Pioneering Women of Bluegrass, where both Hazel and I as well as Peter remembered some of the details: “I heard you guys sing in the kitchen and I thought you were great singers and I was totally knocked out.” [Peter]. “I remember us sitting on the floor and singing. David and Peter . . . asked if we’d ever thought of recording. . . . David said we’d need to get a tape together and he would speak to Moses ‘Moe’ Asch, owner of Folkways Records. We [recorded the demo tape] in Pete Kuykendall’s basement.” [Hazel]. Peter thinks that Mike Seeger, who had recorded several LPs of traditional music for Folkways and had a good business relationship with Moe Asch, also put a good word in for us.

Moe, a Polish immigrant and son of writer Sholem Asch, founded Folkways Records in New York in 1948. The label was known for putting out huge collections of rare, little-known music and spoken-word recordings of all kinds. “He recorded the world” as someone recently noted.

Some of these recordings became classics and were revered around the world—Leadbelly, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Ella Jenkins, and countless others. Others remained known to few or to specialized audiences, but all were available and remain so to this day through Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Given Moe’s wide and varied taste, and perhaps a little prodding from Mike, he agreed to put out a recording of Hazel & Alice. I found a contract that I think is for the first recording of Hazel Dickens and Alice Foster (that was me) dated November 17, 1965. From what I can tell, we were paid $200 with a $75 advance against royalties of 25 cents for each album sold. We were thrilled.

Our first recording! Our good friend Lamar Grier (d. 2019) would play banjo, Hazel the bass, David Grisman the mandolin, and I guitar. All we needed was a fiddler. Robert Russell “Chubby” Wise, a well-known bluegrass fiddler who had played and recorded with Bill Monroe, among others, happened to be living in the DC area at the time, playing at the Famous Bar & Grill across from the Trailways Bus Depot in downtown Washington.

Jeremy thought it would be quite a coup if we could get Chubby to play with us on the recording, but we had never met him. Tom Morgan, a close friend and fellow musician who knew him, gave him a call. Tom said, “I have some friends who are trying to cut an album, would you be kind enough to help them out? I like to have dropped my teeth when [Chubby] said, ‘Yeah, I’ll do it.’ He was congenial and supportive.”

He was, indeed, chubby, happy, smiling a lot, and all about getting the job done. This was before ProTools. As Peter remembered, “It was one AKG-D24 microphone, a borrowed Nagra III P tape recorder, acetate tape, borrowed speakers [so Peter could play the takes back for us to hear], and mostly one- or two-take songs.”

Peter remembers that Moe Asch gave him $75 to make the recording, $37.50 so he could buy tape and a bus ticket, and the other $37.50 when he was finished. “I thought it was big-time,” he said. “I bought twelve reels of tape and a bus ticket.”

Hazel and I were busy planning the recording, choosing material, and practicing. It was during this time, in September 1964, that Jeremy was killed. Peter remembers wondering whether we’d go through with the recording or not, but we did, probably in early 1965, with a lot of help and support from many friends. We recorded in Pierce Hall, part of the All Souls Unitarian Church at Fourteenth and Harvard Streets in Northwest DC—a hall known by music people for its good acoustics. Hazel remembered that it cost fifty dollars to rent.

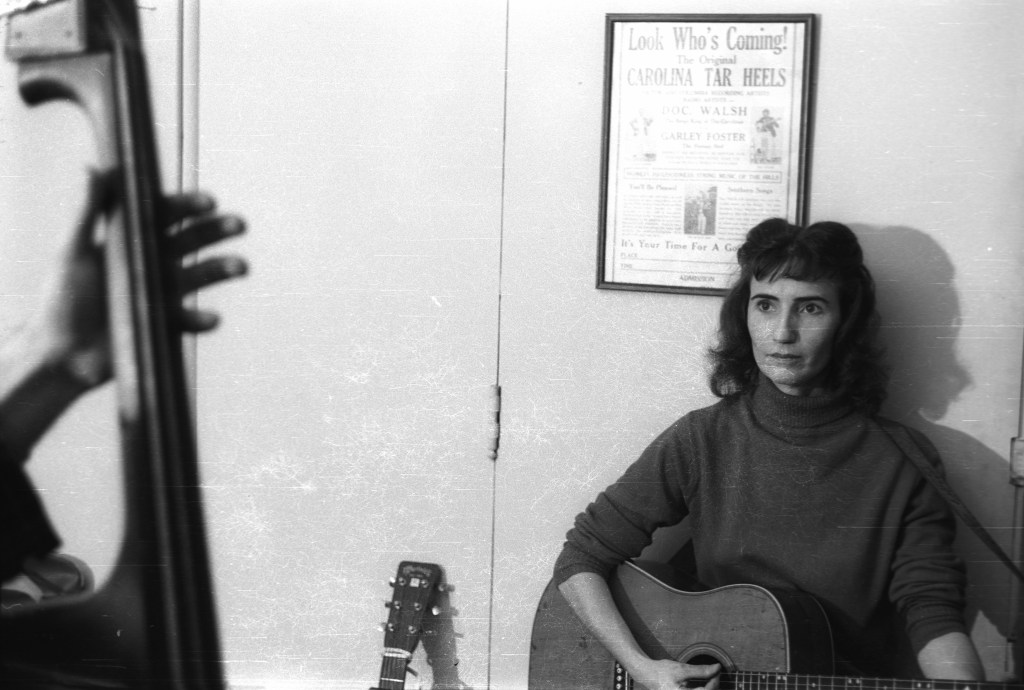

Hazel and I recorded a second album for Folkways shortly after the first one, Won’t You Come and Sing for Me. It wasn’t released until 1973, at about the same time that we released our first Rounder Records album. (Apparently, Moe had forgotten about it.) My friend Betsy

Siggins took a number of wonderful photos of Hazel and me at this time, which we used for the cover of Won’t You Come and Sing for Me. I remember those photo sessions—lots of messing around, indoors and out, trying different backgrounds, lighting, props, outfits. She had cool old furniture in her house, and lots of old pieces of clothing: boas, peacock feathers, net stockings, cigarette holders, and the like that we worked with when we got fed up with playing it straight. Why not mess around? Put three creative women together with a camera and props and watch out!

To comment on this story, email [email protected].