Northgate Mall, once an economic hub, was in decline for years before Northwood Investors purchased the site in 2018 with plans to transform the former shopping center.

In 2020, the mall permanently shuttered, followed by the 2023 closure of its adjacent movie theater.

In the meantime, Northwood Ravin, the development arm managing the construction process, has put forth various proposals that featured a mix of market-rate housing, retail, office space, a hotel, a park, and lab space. Residents in neighborhoods adjacent to Northgate Mall—like Walltown, Trinity Park, and Northgate Park—pushed for any redevelopment of the site to include affordable housing and other amenities that would benefit the neighborhoods rather than exacerbate further displacement.

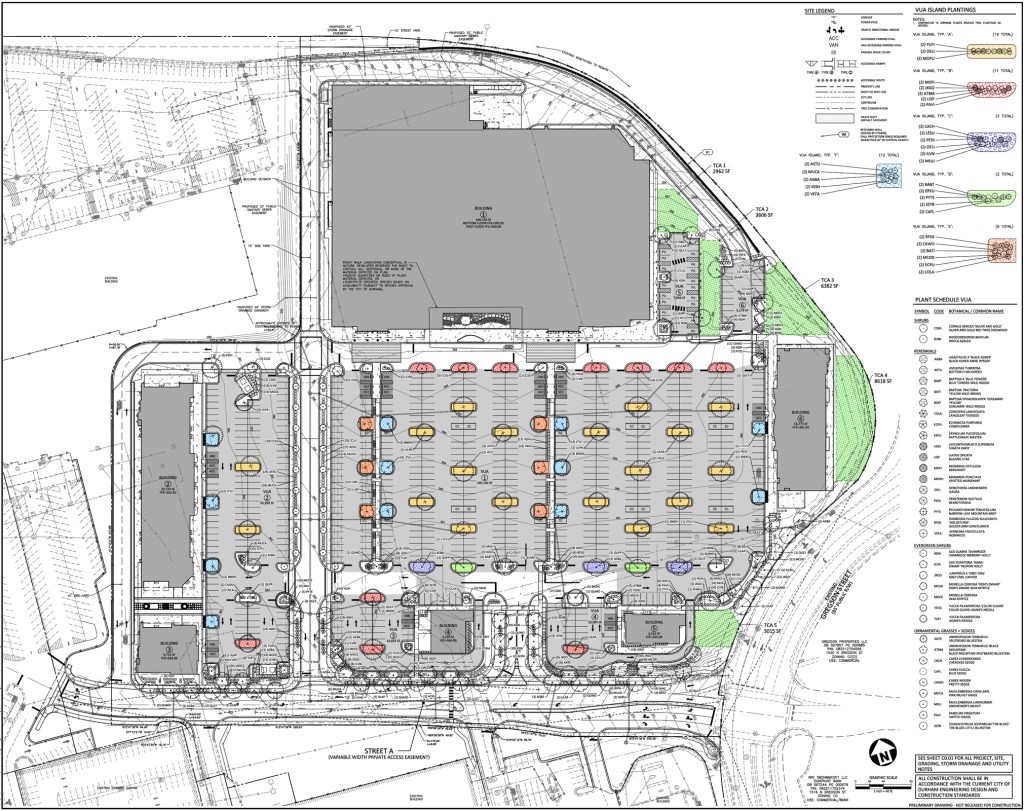

But after years of negotiations between Northwood and residents failed to reach a consensus, a new company has submitted plans for a part of the site. Regency Centers, a Florida-based development firm, is in the process of purchasing about a third of the site from Northwood and, in October, submitted plans for a 190,000-square-foot development that calls for the demolition of the mall, a 620-space parking garage, and the old Stadium 10 movie theater.

In its place, the firm plans to construct a 140,000-square-foot building ripe for a big-box retailer; five additional buildings, ranging from 3,000 to 20,000 square feet each, for retail and restaurant space; and 762 parking spaces. The new shopping center will be called Ellerbe Square.

“Our focus is to reactivate a long-vacant portion of the site and bring back essential retail and neighborhood-serving uses,” said Chelsea DuDeVoire, Regency Centers’ communications manager. “The plan includes an anchor that will bring back dependable everyday essentials and help meet daily retail and grocery needs in the area. While early leasing discussions are underway, a curated mix of additional retailers could include food and beverage, health and wellness, and small shops.”

It looks as though the new site plan will not include the proffers and amenities requested by neighboring residents, and because the plan—a mix of commercial uses—has nearly the same zoning requirements as the mall, the developer can move forward without city council approval. Brandon Williams, chair of the Northgate Mall Committee for the Walltown Community Association (WCA), helped organize residents around creating a “small area plan” for Walltown that included a vision for the redevelopment of Northgate Mall. Williams described Regency’s plan as “a bit underwhelming.”

“Particularly given the years spent working on the small area plan and trying to officially instantiate the priorities we’ve advocated for … there’s not a process by which to enforce them, but I think it reflects a bit of tone deafness on the part of the developers,” Williams says.

Walltown Community Association has spearheaded the public engagement process with Northwood. In a statement released by WCA last Thursday, Williams said that “Durham deserves a transformational redevelopment of Northgate Mall, one that turns the mall into a place where all Durham residents—including those in the working class—have the opportunity to live, work, and play.”

Northwood Investors retains partial ownership of the site, and plans for those parcels are unclear. Williams and other community members say they remain optimistic about bringing Regency and Northwood to the table to reach a compromise for the overall redevelopment, but how much input neighbors will have in the future is up in the air.

Before Northgate Mall was built in 1960, Coca-Cola intended to relocate its Durham manufacturing plant to the site, but the industrial use was rejected by neighbors. Instead, the Rand family, who owned the land, built Northgate Mall, following the trend of other shopping centers like Lakewood and Wellons Village that were constructed at that time.

Northgate Mall was an economic engine in the area for decades, offering retail, food, entertainment, and jobs. As a kid, I used to walk from my family’s home in Watts-Hillandale to the Sports Cards Unlimited store on Saturdays to play Yu-Gi-Oh. (Before e-gaming became a viable—and lucrative—profession, my friend Ian and I won $200 in a Halo tournament at Northgate’s Gamefrog gaming café when I was 12; my parents had to sign a permission slip because the game was rated M for mature.)

But by the 2000s, Northgate, with traditional retail bays, food court stands, and classic carousel, was no longer the retail belle of the ball, outcompeted by downtown and higher-end Southpoint. Northgate Associates took out millions in loans to buoy the operation, but the investment wasn’t enough to stave off the decline. Toward the end, Northgate’s main attractions were the DMV license place office, and fittingly, driving practice in the vast empty parking lot.

When Northwood Investors purchased the site from the Rand family in 2018, it agreed to take on the $62 million in debt Northgate had accrued. In response to the mall changing hands, residents from the neighborhoods that surround the mall—Walltown, Northgate Park, Duke Park, Trinity Park, Trinity Heights, Old West Durham, and Watts-Hillandale—formed the Northgate Mall Neighborhood Council (NMNC), which organized residents around a shared vision for the future of the mall site. At the same time, Northwood began its public engagement process.

Negotiations got off to a rocky start. In the fall of 2020, Northwood circulated preliminary design concepts that showed a mix of residential and commercial uses. The NMNC responded after conducting its own public engagement, requesting substantial affordable housing, affordable retail space, a transportation hub, community gathering space and resource center. Northwood pushed back on carrying the responsibility of meeting neighborhood needs.

“While we sympathize with the desire of the neighbors to have more affordable housing and affordable retail next to their homes,” Jeff Furman, former Director of Raleigh Operations for Northwood Ravin, wrote in a May 2021 email to then-mayor Steve Schewel, “this request for action needs to be directed to the City of Durham and its elected officials. Not to fellow private landowners.”

“Asking private landowners to solve the City’s issues is a misdirected mission,” Furman continued.

Even if Furman was right that Northwood could not solve Durham’s affordable housing challenges on its own, the public dismissal of Walltown residents’ concerns did not ingratiate Northwood with the community, and the firm still needed rezoning approval from the city council. That gave NMNC leverage on its demands; the group successfully petitioned the city council to hold out on granting Northwood its zoning while the community continued to develop a more concrete plan for rehabilitating the old mall.

Over the past seven years, various plans have surfaced from both camps, but between shifts in the market, and pushback from residents, none have made it to the Durham planning department.

During his run for city council, Nate Baker, a professional urban planner who served on the Durham Planning Commission from 2018 until joining the council in 2023, seized on the opportunity to coalesce Walltown residents, and potential voters, around small area plans—specific visions for individual neighborhoods within the city’s comprehensive plans.

Small area plans have no legal authority, but they are useful for steering decision-making around development and establishing development laws. Those legally binding ordinances are one of the few mechanisms that municipalities have to enforce design standards on private landowners. Baker, now the vice chair of the Durham Joint City-County Planning Committee, says Durham could have done its own rezoning of the Northgate property prior to Northwood’s involvement. He called Regency’s proposal “deeply disappointing.”

“We had a whole lot of leverage for many, many years,” Baker says. “We just kind of took our hands off the wheel. We weren’t looking at major opportunity sites and thinking about what would be best for the city of Durham, for our community, and for our people, and just kind of allowed things to continue as they were with bad zoning in place. So as a result, the landowner can do a lot of things that they want to do, and one of those things is just to build big-box stores surrounded by parking.”

In August, after years of back-and-forth, the City of Durham approved the Walltown Small Area Plan.. Residents and city council members, including Baker, celebrated the achievement. But even with the vision for Walltown’s future officially etched in the public record, Northwood and Regency still have the power to build without the need for city council approval. The small area plan, though it could inform future elements of the Walltown neighborhood, might be too late to impact the Northgate Mall site.

With a plan sketched out for the part of the site that Regency plans to purchase late next year, community engagement for that portion seems likely to end. DuDeVoire tells INDY Regency has no immediate plans for public engagement on the site but “recognizes the Northgate property’s long history of community engagements and has reviewed feedback that has been shared in past public processes.”

Still, Williams and Baker are cautiously optimistic that Regency will come to the negotiating table (Regency says no one from the WCA or Durham City Council had reached out to discuss redevelopment plans as of November 17.)

“We don’t know what the outcome is going to be yet,” Baker says. “First of all, there have been multiple submittals on the site, all of which have been inadequate. I mean, the lesson is, if you don’t do planning, good things won’t happen.”

While specific details about potential tenants haven’t been released, renderings as well as the track record of other properties operated by Regency Centers suggest a big-box store will anchor the new strip mall. Regency Centers already operates three other shopping areas in Durham—Shops at Erwin Mill, SouthPoint Crossing, and Woodcroft Shopping Center, none of which suggest that the new Ellerbe Square project will include the high density and mix of uses the community and city council have advocated for.

Once the first phase of the new project has begun, retrofitting things like affordable housing and green space will become much more challenging, Williams says. Retail leases for big-box stores tend to last for decades, though that trend could be changing post-COVID. Still, whatever is built on the Northgate site is likely to endure for years, heightening the urgency for residents.

“You want to get it right from the beginning, because when you use half of the site up in this way, that means you just have less of the property to negotiate around for those benefits,” Williams says. “So to me, that makes it harder. But even if we can’t get the shifts on the current site plan, we still want to maintain our ability to negotiate on the remaining property that will still be developed by somebody down the line.”

Regency says it is designing its development to allow for additional uses on other parts of property.

“We see this as the first step in the broader evolution of the property, and we remain committed to ensuring this phase brings back meaningful, everyday retail benefits to the surrounding communities,” DuDeVoire said.

Walltown’s challenge is not unique in Durham. For the past three years, Hayti residents negotiated with Sterling Bay, owners of the Heritage Square, another defunct shopping center, over how to redevelop the site into something that would benefit the local community. After the two parties couldn’t agree on the list of proffers, Sterling Bay rescinded its application in August, leaving the future of Heritage Square uncertain.

Residents prevented what they consider an inadequate project, but, as in the case of Northgate Mall, could end up with an even less desirable outcome if the developer chooses to build by-right on the site or sell the parcel to a developer less interested in collaborating with the local community.

For Williams, Baker, and others, part of the solution is giving residents more bargaining power through the Unified Development Ordinance (UDO), the legal document that governs development in Durham. The planning department is in the process of rewriting the UDO and has hosted dozens of meetings to receive guidance on what residents want to see in the new version, which Baker and his council colleagues will vote on in the coming months.

“What we have in our toolbox as policy makers is carrots and sticks, and that’s how we can push policy that moves us forward as a more sustainable, walkable, and inclusive city,” Baker says. “We have carrots and sticks, and we need to use both carrots and sticks to make sure that we develop in a more walkable and sustainable fashion.”

Northgate Mall won’t be the last commercial site that Durham residents seek to reimagine. What can Baker, the city council’s resident urban planning expert who grew up near Northgate Mall himself, take away from the experience to produce better outcomes for his hometown?

“I don’t think there are any lessons to learn from other than ‘Doing nothing doesn’t provide better results,’” Baker says. “I would love to say we can learn from Northgate Mall on another site, but we haven’t succeeded on anything. We don’t have anything to learn. We can learn from other communities.”

Follow Reporter Justin Laidlaw on X or send an email to [email protected]. Comment on this story at [email protected].