In 1919 a young Dutch architect named Michel de Klerk designed a large, experimental apartment complex called Het Schip, intended to provide hourly wage earning families in Amsterdam with a pleasant, handsome and dignified place to live. The apartments were small but bright, efficient, and comfortable. They were arranged to form a triangular courtyard protected from traffic and strangers; the vertices of this triangle were anchored by a school, a tower and post office. Its acute tip was meant to suggest the prow of a ship steaming towards a nicer future.

Shortly after the first tenants moved in, de Klerk received mail from a woman with small children residing in his new building. She had nothing to say about the modern styling of Het Schip, its unconventional shape, or its nautical metaphors. She wanted to mention a single, ordinary window above the kitchen sink. Thanks to it, she was able to watch her children playing in the courtyard below while she cooked or washed dishes. Without it, she would have been obliged to keep her children inside whenever she was alone. This simple, thoughtful design gesture was transformative. In her letter, she expressed gratitude for a window that made her life measurably better.

The archives of architectural history are full of letters to architects delivering congratulations from a colleague, but a note from a tenant is very rare. It is a reminder that good architecture is foremost physical, spatial, and related to commonplace movements of the human body; it is not primarily visual. Architecture, we might say, accumulates value as positive everyday experiences accumulate within it – no matter how plain or glamorous it appears from the curb.

Around 40 BCE, a celebrated Roman critic named Vitruvius suggested that any building’s quality might be judged in terms of firmness (strength), fitness (convenience), and delight (pleasure). He mentioned nothing about curb appeal or marble countertops. This elegant formula has grown not the tiniest bit stale across the sbusequent 2,065 years. It rings like a bell, and that bell tolls for us. Three simple hurdles – and so few buildings hop over them.

The previous column in this space examined the near-complete failure of artificial intelligence to conceive or design successful architecture. When asked to address a simple building challenge with budgetary limitations, it flubbed the assignment and overspent with reckless abandon. It was noted that this failure is probably due to the scarcity of two essential resources which AI would need to become a skilled architect: 1.) an algorithm which allows it to imagine, with empathy, if possible, what it is like to live inside a thumping, quivering, sleepy, shivering, hungry, sometimes lonely, sometimes anxious body, and 2.) access to a sensibly organized archive of real buildings rated according to functional performance.

Severe disappointment in relation to the first resource is apparently the natural result of bad code. Scouring the fathomless corridors of the internet, the algorithm looks for patterns to learn and imitate. Patterns of speech, logic and opinion a dime a dozen, but encoded information about what it feels like to have tendons, muscles, bones and emotions of outrageous complexity is hard to come by, leaving the aspiring AIrchitect stumbling badly right out of the gate.

By way of confirmation (you never know when you might wake up some morning and find ugly duckling AI transformed overnight into a lovely swan), I gave AI another assignment that would be a cinch for any first-year architecture student:

CAN YOU PLEASE GENERATE A SCHEMATIC ARCHITECTURAL DRAWING IN A PROFESSIONAL STYLE OF A SIMPLE WILDERNESS SHELTER WITH GOOD THERMAL INSULATION PROPERTIES WHICH IS DESIGNED FOR A SOLITARY ADULT WHO IS LOST DEEP IN THE MAINE WOODS IN THE MIDDLE OF NOVEMBER, WHEN TEMPERATURES WILL BE BELOW FREEZING AT NIGHT?

What I got back would have propelled my hiker efficiently both towards hypothermia and mild insanity.

Immediately the algorithm starts babbling, pointing out nonexistent elements, recommending materials that cannot be found in the Maine woods, proposing structural details that cannot be composed by hand, tossing in wood stoves to get out of the November warmth problem, and all this in a shelter just twelve inches wide. In its confusion, it forgot how big my lost adult’s body must be – something even a five year old would get right. In sum, AI choked just as the sun was setting and my disoriented hiker really needed its gigabyte brain to deliver the goods.

This exercise proved so embarrassing that I felt a bit mean for even having brought it up. Is this ineptitude some kind of practical joke? A clever simulation of stupidity generated for my amusement? This is the same brain, I am told, that can explain Newton’s Laws of Thermodynamics or String Theory without breaking a sweat. In any case, to lean on the side of caution I drastically simplified the assignment. Never mind structural details and schematics; perhaps AI can just be so kind as to walk my hiker through an emergency shelter with a few basic directions?

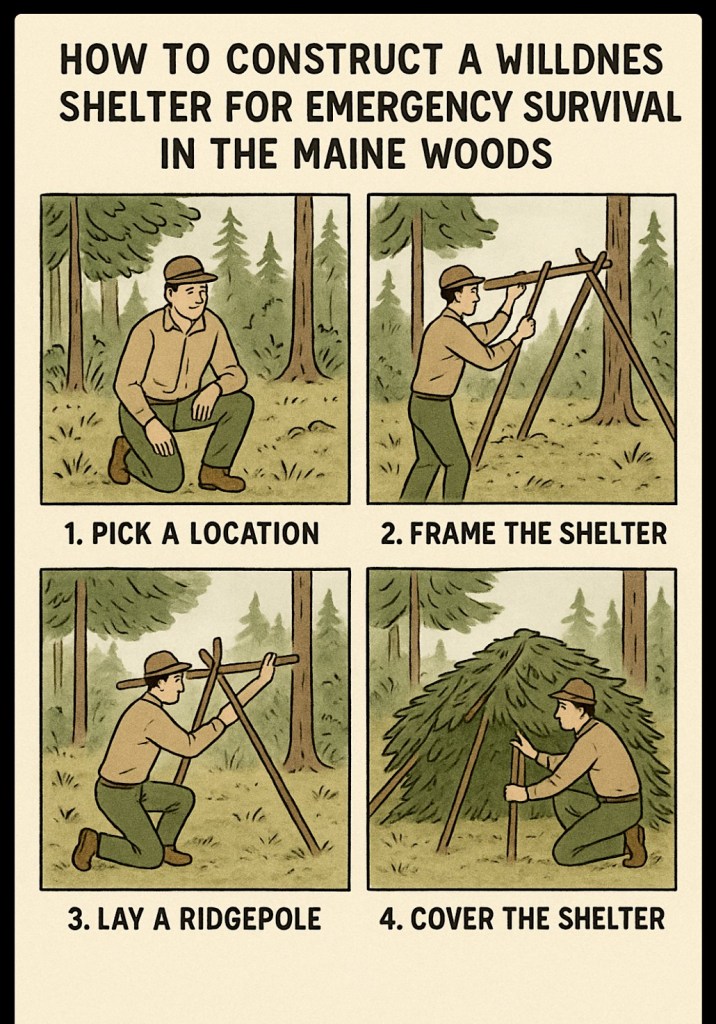

PLEASE DRAW A HOW-TO GUIDE FOR CONSTRUCTING A WILDERNESS SHELTER FOR EMERGENCY SURVIVAL IN THE MAINE WOODS.

Did this make things even worse? Does some cynical server snicker at me because it is bored?

My exhausted and desperate hiker at creeping dusk has been transformed into a well-nourished Boy Scout troop master in broad daylight. His arm is growing ominously long while trying to balance a ridgepole on two crossed sticks. Impossible. Any self-respecting toddler would reject such a plan at the theoretical stage.

Paranoia settles in. Surely no machine is this idiotic? A deep-pocketed architectural Super PAC has sabotaged the code because it wants to buy some time. These sociopathic Illuminati have it out for architecture critics in particular and are trying to lure us towards a sad, clumsy wilderness death.

Ah, but let me get a better grip of myself. There was a second factor to weigh: access to a logically-arranged index of functional quality for architecture. This index could contain simple anecdotes like the Dutch mother’s courtyard view at Het Schip, but they must be sorted in a way that allows for patterns to be detected. Without a pattern, without a reliable and consistent feedback loop generating meaningful linkages between particular architectural details (window, kitchen layout, roofing material, heating system, etc.), architectural design cannot be learned, or even usefully imitated, by AI.

The missing analytical loops which cause AI to stumble so badly with elementary problems like those above also impose serious constraints on human architects while they wrestle with universal problems like thermal regulation, ventilation, precipitation, sleep, security, hygiene, food storage and preparation. Please suspend disbelief to picture a surgeon who finishes the last appendectomy of the day, but fails to inquire the next morning about whether her patients flourish, suffer, or have passed away. “One does what one can do.” Those next in line and doubled over, however, may very well like to know!

The disaster that is AI at the drafting table today sheds some light on an Achilles’ heel of the architecture industry, which is entirely human in origin and predates the printing press. Possession of a body, exercise of the imagination, and having once gotten lost in the woods can count for a lot. Still, we would see many more firm, fit, and delightful buildings if all buildings, the delightful and the terrible, received report cards graded on a curve.

Recently restored, Het Schip sails on in Amsterdam, occupied by 82 working class families and still serving its original function.

The next column in this series will examine the most promising and practical contributions artificial intelligence can make to the improvement of the built environment.

Jon Calame teaches art history at the Maine College of Art and Design and the University of Southern Maine. This column is supported by The Dorothea and Leo Rabkin Foundation.