Mandy McGhee’s cousin had come to pick her up for a trip to the grocery store. But first, there was something he needed to show her. He led her around the side of her feather-gray house on Berkeley Street in Durham’s Walltown neighborhood. There, a section of her home’s foundation had collapsed, leaving a wide cavity that exposed the dark interior of her crawl space.

“Did you know about this?” McGhee’s cousin asked. She hadn’t. But she wasn’t surprised.

A few paces from the site of the collapse, a stormwater pipe opens onto McGhee’s property. It’s been dumping water there ever since McGhee moved into her home 28 years ago—and probably for years before that. What McGhee’s cousin discovered that day this spring was the culmination of decades of erosion.

The mouth of the concrete pipe, two and a half feet wide, is half-hidden in an overgrown tangle of vegetation. Its steady flow long ago turned McGhee’s side yard into a permanent wetland teeming with tadpoles.

The pipe collects runoff from an approximately nine-acre drainage area, according to Michele Eddy, a Durham-based environmental engineer who spoke in her personal capacity. Eddy calculated the drainage area using publicly available data.

It’s an unusual setup, Eddy says—runoff from an area roughly the size of seven football fields, bearing down on one homeowner’s 0.19-acre yard. And the flow has no doubt intensified over the past decade. As climate change has brought heavier rainfall, and as development has intensified in the area between Duke University’s East Campus and the defunct Northgate Mall, the volume of water coming from the pipe has grown, putting pressure on aging infrastructure. During a single storm in August, Eddy calculated, 700,000 gallons of water flowed onto McGhee’s property.

McGhee bought her home from Self-Help in 1997 through the community development organization’s Walltown Homeownership Project—a program designed to help low-income, first-time buyers purchase renovated homes in the historically Black Walltown neighborhood and build generational wealth.

Nearly three decades later, the pipe is threatening to destroy what the program was meant to create.

Earlier this year, Durham County valued McGhee’s property, which she bought for $70,500, at $336,971 based on rising values across gentrifying Walltown. In September, after an appraiser came to the site in person and documented the damage to the foundation—attributing the damage to a “city drainage pipe along side of dwelling”—the county reduced the property valuation by nearly 40 percent to $211,439. The house itself is now worth just $21,783.

McGhee’s property sits in a flood zone, and she carries both regular homeowners insurance and flood insurance. She filed a claim to see if the foundation damage would be covered, but it was denied. Now McGhee says her insurance company may drop her coverage entirely due to the damage. That could leave her in breach of her mortgage and facing potential foreclosure.

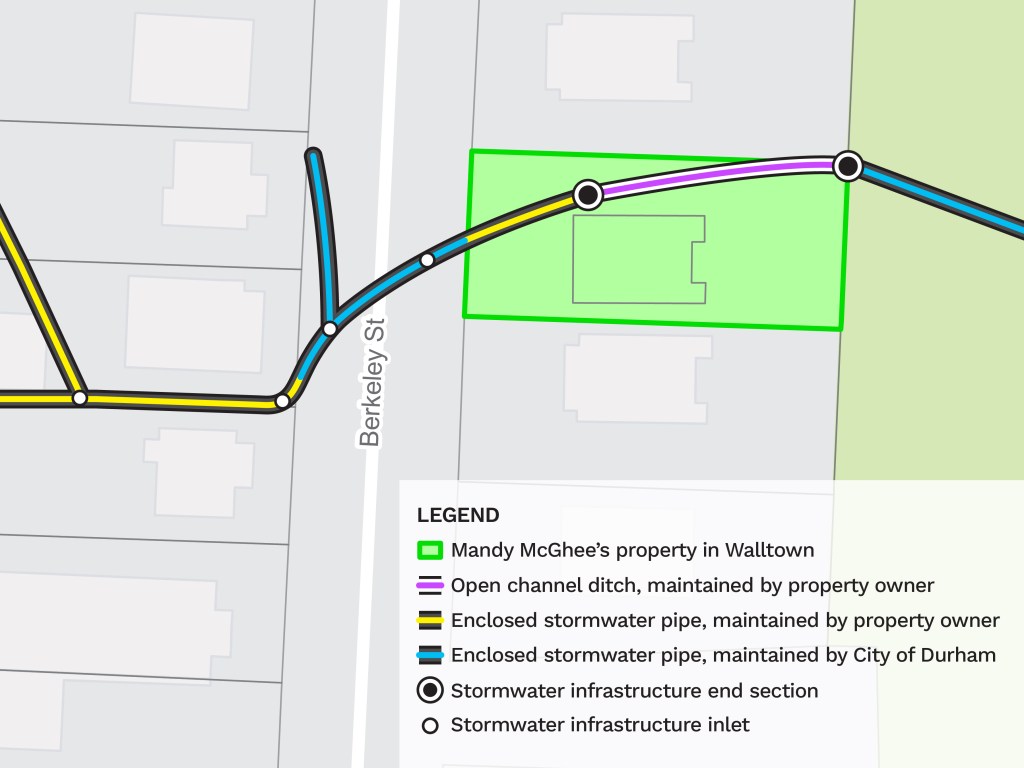

The pipe is attached to city stormwater infrastructure, and its ownership is listed as “shared” in the city’s Geographic Information Systems (GIS) database. So in July, with help from her neighbor Rafael Mazer, McGhee reached out to the city requesting help. The ask seemed straightforward: there’s another open stormwater outlet behind McGhee’s backyard, right down the hill from the one that dumps on her land. In an email, Mazer asked that the city simply connect them.

The city’s response: the drainage system is on private property, so it’s McGhee’s responsibility to address.

Over several exchanges, Mazer pushed for clarity. How could the city require McGhee to maintain a pipe carrying runoff from multiple blocks? And hadn’t the city installed the pipe in the first place? The city reiterated to Mazer that property owners are responsible for drainage systems on their land, and stated that the city has no records showing when the pipe was installed or by whom—though the city believes it did not install it.

Eventually, Mazer asked if McGhee could just seal off the pipe. The city said no, citing an ordinance. McGhee cannot modify the pipe without obtaining a permit, and regardless, any modifications cannot impede the flow of water.

“It feels like there’s a Catch-22 they’ve put us in, where they’ve said that what falls on Mandy’s property is her responsibility, but also that she needs their approval to do any adjustments or remedies,” Mazer says.

In a statement to the INDY, a spokesperson for the City of Durham wrote that “There is no indication that the City ever accepted or controlled this private system, which means the City is not responsible for it.”

McGhee grew up in Person County, the middle child in a family of six girls and two boys. Her father was a tobacco farmer—the first one in the area to get $1 a pound for the crop, she says.

She’s never been one to stay quiet when she sees injustice. During her senior year of high school in 1975, after school administrators announced they were updating the dress code to ban halter tops and miniskirts, McGhee led walkouts every day for a month.

In 1984, after graduating from Piedmont Community College, McGhee moved to Durham, looking for work opportunities she couldn’t find in Person County. She got a job washing dishes and eventually became a certified nursing assistant while raising twin sons by herself.

McGhee heard about Self-Help’s Walltown Homeownership Project in the mid-1990s. At the time, she and her sons were living in a rented apartment two streets away from where she lives now. She decided to apply.

The Homeownership Project required McGhee to attend classes on first-time home buying and home maintenance. After McGhee completed them, she was able to receive down payment assistance and buy a home renovated by Self-Help.

During her final walkthrough before closing, McGhee says she asked Self-Help representatives about the stormwater pipe.

“I was standing right here in this room,” McGhee says, gesturing around her kitchen, which is tidy and filled with plants, decorative china mounted on the walls. “I said, what are they gonna do about that?”

McGhee says Self-Help representatives told her that the city was aware of the pipe and would take care of it once she moved in; she just needed to call and ask.

So McGhee called the city, she says—numerous times in the months after she settled into her new home. McGhee says each call involved being transferred in a loop. After her third attempt, she gave up.

“If I had known that the city was not gonna take care of that problem, I never would have signed that [purchase] agreement,” McGhee says.

The city told the INDY it has no records of McGhee’s inquiries from the late 1990s.

Jenny Shields, a spokesperson for Self-Help, wrote in a statement that the organization “can’t speculate on what transpired” regarding McGhee’s recollection that Self-Help representatives told her the city would fix the drainage issue.

“What I can say is that we’re very interested in working with Ms. McGhee and the City to see if we can find a resolution to this situation,” Shields wrote, adding that McGhee reached out to Self-Help in October and the organization offered to meet with her to “determine what, if anything, we can do to help.”

“I think the City ordinance is clear and describes whether the property owner or the City is responsible for maintenance, depending on where the infrastructure is located,” Shields continued. “In spite of this, we want to find the best solution possible, and we’re working with Ms. McGhee and the City to see how we can best assist with this.”

The city ordinance Shields referenced states that “maintenance of drainage systems, both surface and underground, located on private property, is the responsibility of the property owner.”

This is what makes it permissible for a sizable stormwater system—starting with city-owned inlets and extending through hundreds of feet of shared infrastructure across multiple properties—to culminate in a single 60-foot-long pipe that dumps onto McGhee’s property.

The pipe’s “shared” ownership designation in the GIS database reflects a division of responsibility, a spokesperson for the city told the INDY: The city is in charge of the 20 feet that run up to McGhee’s property line. McGhee is responsible for the remaining 40 feet of pipe on her land and everything that pours out of it.

“The drainage channel at this property does not appear to have had adequate erosion protection, which has allowed it to migrate closer to the home’s foundation,” the spokesperson wrote.

McGhee contends that she has maintained the drainage system as best a person could. In the first decade she owned the house, she personally cleared trash and debris and hauled away a tree trunk to try to keep the water flowing. After she developed congestive heart failure in 2011 and couldn’t do the labor anymore, she started hiring people to clear the pipe, she says.

Also in 2011, McGhee fell behind on her mortgage payments as medical bills mounted, and her mortgage company threatened foreclosure. To avoid losing her home, she agreed to extend her loan by 20 years. A mortgage that was supposed to be paid off in 2022 now won’t be satisfied until 2042, when McGhee will be 85.

Watching her home’s foundation fall apart while dealing with the bureaucracy around the pipe has triggered memories of that near foreclosure. Without Mazer, whom McGhee met at a community association meeting, she doesn’t know how she’d manage, she says. She lovingly calls him her secretary.

Mazer sees helping McGhee as putting into practice what he’s learned from longtime Walltown residents about the work required to sustain their community.

“I moved here recently,” says Mazer, who grew up in Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts. “My presence, or the presence of people like me in this neighborhood, is at best complicated, at worst harmful.”

McGhee has quite a few health problems. Beyond congestive heart failure, she has stage 3 kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and severe allergies to everything from pollen and contrast dye to watermelon.

“Can you imagine, a Southern girl who can’t eat watermelon?” she says. “I’m in my own little private hell.”

Her kitchen table is stacked with after-visit summaries from Duke Health. Midconversation about the pipe, she reaches for one of the summaries and flips it over. She draws a diagram—several lines converging at a single point, which she circles over and over.

When it storms, the water from the network of pipes that feed into the one on her property “comes through as a jet,” she says, tracing the lines with her finger.

Danielle Spurlock, a professor of land use and environmental planning at UNC-Chapel Hill, says for a pipe that’s draining water from such a large area, you would expect McGhee’s property records to include an agreement establishing who’s responsible for it.

The INDY went to the Durham County Register of Deeds office to review McGhee’s property records. Her deed contains no mention of a drainage easement or any agreement about who is responsible for the stormwater pipe. The plat map on file dates to 1945 and contains no information about drainage infrastructure. The INDY reviewed over a dozen additional deeds and maps linked to the property, none of which have information about the pipe.

Self-Help directed the INDY to the city for records that might clarify responsibility for the infrastructure, and the city told the INDY it has “found no records or evidence in its inventory of historical as-built drawings or GIS data showing installation, approval, or maintenance of the drainage system.”

The city added that before 1994, property owners could install drainage systems without city oversight or approval. That means there may be no official record of who installed the Berkeley Street pipe or when it was connected to city infrastructure.

McGhee’s home was built in 1920. The property passed through the estate of James B. Warren—a bank vice president and city councilman—and subsequently belonged to a U.S. postmaster, a Golden Belt factory foreman, and a general contractor before Robert Rosenstein, an optometrist who owned dozens of homes in Walltown, acquired it in 1953.

In 1994, Rosenstein decided to sell. Self-Help, which had experience financing affordable housing but had never actually developed it, saw an opportunity to expand its work. The organization wanted to increase homeownership rates among underserved communities, and Walltown seemed like a good place to start.

Walltown was founded around the turn of the 20th century by George Wall, Duke University’s first custodian after gaining his freedom from slavery, and became home to generations of Black working-class families, many of whom worked at Duke. By the 1990s, the neighborhood faced challenges common to communities that had experienced disinvestment and discriminatory lending practices: Only 20 percent of housing was owner-occupied, and many families were at risk of displacement by gentrification.

Self-Help negotiated to buy all 30 of Rosenstein’s Walltown properties for $11,000 each. The properties were “low cost rental houses” that “had been poorly maintained,” a 2008 report Self-Help produced to assess the Homeownership Project notes.

With funding assistance from the City of Durham and Duke University, among other partners, Self-Help renovated and sold those homes, plus more than 40 others, over the next decade.

Self-Help Director of Real Estate Dan Levine told the INDY renovations were “done by qualified general contractors and (of course) inspected and certified for occupancy by the City.”

Yet the pipe on McGhee’s property was seemingly never addressed during the renovation or inspection processes.

In the 2008 report, which Shields shared with the INDY, Self-Help’s “lessons learned” acknowledge struggles with preparing homeowners for routine upkeep: maintaining central air conditioning systems, cleaning gutters, setting aside money for eventual repairs. There is little reflection in the report on how developers should assess pre-existing environmental and infrastructure risks when selecting properties to renovate.

Spurlock says it’s crucial to assess site conditions before selling homes to first-time buyers who would have limited resources to address such issues.

“When we place affordable housing in places at risk,” she says, “we’re also placing individual homeowners at risk of having to do even more maintenance than the average homeowner in the same area.”

McGhee isn’t the only person who bought a home through the Walltown Homeownership Project who is facing serious water problems.

Trudie Watson purchased her home on Lancaster Street from Self-Help in 1999. Like McGhee’s, the home is a former Rosenstein property built in 1920. After several years of flooding issues, Watson went to the Register of Deeds and discovered that at some point before she moved in, a creek behind her house had been buried. Self-Help never told her about the buried creek, she says. When heavy rains come, the contours of Watson’s yard funnel water down toward her house, pooling around her foundation. Sinkholes have opened up across her property.

Half a block up the street, Carline Jules, who bought a home on Lancaster Street from Self-Help in 2007, has similar, though less severe, issues. When it storms, water collects under her porch and sits for extended periods, saturating the wood and creating conditions for mold. Over time, this has caused her porch to shift, and Jules worries it may eventually collapse.

In September, Watson appealed her property valuation of $373,675. After an appraiser came to the property and documented the water damage, the county reduced it by $28,000.

Jules also tried to appeal her property valuation this year but was unsuccessful. Now she’s focusing on what she can personally do to manage the water, like digging trenches filled with gravel and planting a “rain garden” to aid absorption.

Levine told the INDY Self-Help is reaching out to Watson and Jules.

“We totally understand the nature of global warming means flooding has become more of an issue, not only in Walltown, but across the city and beyond in ways that were unheard of 30 years ago,” Levine wrote, adding that the work Self-Help did throughout the Homeownership Project decades ago “doesn’t address the broader issue of extreme weather events, problems with public infrastructure, and topographic challenges.”

For McGhee, the clock is ticking. She says her insurance company has given her until March to repair the damage to her foundation. She wants the city or Self-Help to address the pipe first—it wouldn’t make sense to repair the foundation if the pipe is still eroding it, she says.

Her immediate priority is getting her property valuation lowered even further than it was already reduced earlier this year. She has a hearing to appeal her most recent valuation on November 12. She’s hoping to get the value of her house reduced to zero.

The goal isn’t building generational wealth anymore, she says. It’s simply to stay in her home.

Follow Staff Writer Lena Geller on Bluesky or email [email protected]. Comment on this story at [email protected]