Since at least the late 1960s, feminists have contended that the personal is political. It makes sense: Our politics are built on our values, religions, family structures, relationships. Politicians often talk about love and fear, but they rarely invoke grief — something all of us inevitably experience but which is often kept intensely private.

“Do We Say Goodbye? Grief, Loss, and Mourning,” at BCA Center in Burlington through January 24, pulls together the personal and political in a deeply felt and powerful exhibition of works by eight artists.

Curator Heather Ferrell started planning the show two years ago, she said, hoping it would “open a conversation and address the swell of grief and loss we all seem to be experiencing as a community — and to serve as a safe place to reflect, heal, grieve, and remember with joy those we love, and lost.”

One of those was Ferrell’s husband, David Del Piero, who died in March. Her experience has informed the show, which includes written reflections on the artwork from psychologists and therapists in the Vermont Association for Psychoanalytic Studies, one of BCA’s exhibition partners.

Ferrell also organized an October 23 standing-room-only conversation about art and grief with John Killacky and Lydia Kern, two of the artists in the show; and Ernie Pomerleau, a prominent community member whose experiences with the deaths of his sister and daughter affected both his philanthropy and his philosophical outlook.

Killacky explained that the impetus for “Corpus,” his six-minute video and installation, was his sense of loss and helplessness after the 2024 presidential election. “I’m 73, I’m queer, I’m paraplegic, and I felt all my friends were at risk,” he said.

He invited 16 community members to collaborate on the video, which offers close-up views of different body parts. Each person chose a part of themselves to focus on — an elbow, an eye made up as though for drag, a scar — that they felt needed reclamation or was in danger of being “lost,” as he put it. (Many of the participants are queer or have disabilities, and the ongoing medical interventions they require might become impossible under the new regime.) Though Killacky initially envisioned the video as an act of affirmation for marginalized identities, he said that for many participants, it became about their pain or trauma.

“By sharing in such an intimate way, it became cathartic for them and for me as well,” he said.

Photographer Jordan Douglas also portrays grief as a series of parts — a catalog of objects that belonged to his mother, a Holocaust survivor who died in 2022. Among items such as family photographs, spoons, a lighter and handwritten notes, Douglas includes an image of the Star of David she was forced to wear as a child. The work underscores that both personal and collective histories of grief can be inherited.

“Personal loss versus loss at a massive scale, are they the same or different?”

Elizabeth Goldstein

Bethany Collins’ series “I can not remember” makes a similar point with devastating simplicity. On black paper, without ink, she has embossed post-Civil War-era letters to the editor from people seeking their formerly enslaved relatives and friends. Details are scant: Many can’t remember the names of their siblings or parents. The raised letters are barely discernible — as though the history of their loss is being lost all over again.

A strong sense of materiality pervades Kern’s sculptures, as well. She was studying social work at the University of Vermont when her sister died about 10 years ago, Kern said; her practice ever since has been informed by that grief.

Using materials such as embalming thread, a double-yolk eggshell and a “double-headed sunflower from June farm (planted after Vermont floods),” she incorporates poetic specificity into “Ghost Twin” and “Double Sorrow Double Joy,” while keeping elements of her story private. Her careful handling of Technicolor resin and plastic sheets transforms what could be garish substances into tender remembrances. The works combine the formality and ritual sensibility of a medieval reliquary with the poignancy of a bouquet of flowers left to molder after a vigil.

Visitors shouldn’t miss Mariam Ghani’s video “There’s a Hole in the World Where You Used to Be,” installed on BCA Center’s second floor; the artist will talk about the piece on Wednesday, November 5. The 15.5-minute video, divided into chapters, features images ranging from the banal, such as a view of the floor or a couch, to news footage to home movies. It juxtaposes these with visuals of space and a vibrating black hole that seems to suck you in. Short written phrases pop in, such as “How do we mourn without occasions?”

Ghani captures the sensation of missing time, of flagging attention alternating with heavy emotion, that can accompany grief. In her reflection on the piece, psychologist Elizabeth Goldstein wonders, “Personal loss versus loss at a massive scale, are they the same or different?”

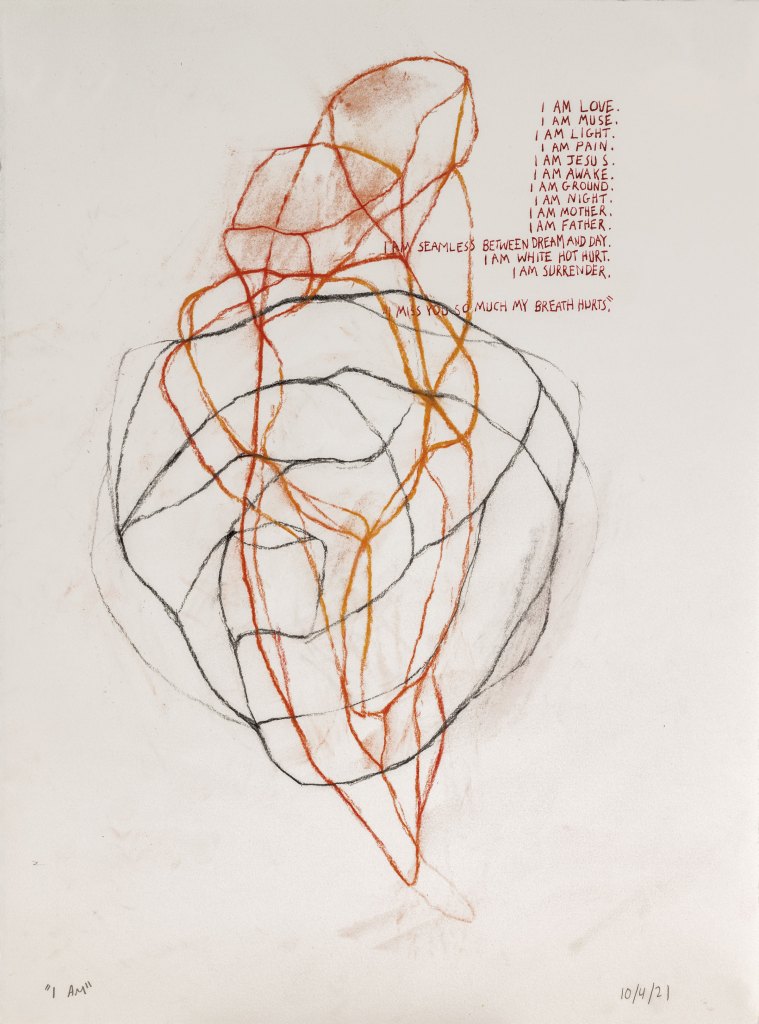

Both scales exist in Peter Bruun’s works on paper, which center on the death of his daughter Elisif from a heroin overdose in 2014. In these abstract line drawings, some of which include text, many of the lines are erased or painted over with white gouache and drawn again — shaky and doodle-like, as though their creator was simultaneously searching for something and simply passing the time. The handwritten text is utterly heartbreaking. “You hugging me, / Neither of us knowing / For the last time. / I still smell your hair in my dreams.”

Many of Bruun’s works hang near BCA Center’s back door, which opens onto City Hall Park. One can’t help but feel the resonance between the private pain of his pieces and the public space where many unhoused people have likewise lost their loved ones or parts of their own lives to substance use.

At the edge of the park, Kern has just installed “Anthology,” an archway of flowers pressed into brightly colored resin. While it’s not part of “Do We Say Goodbye?,” it could be included. Remembrance and recovery, the outdoor sculpture seems to say, should be for everyone.

“Do We Say Goodbye? Grief, Loss, and Mourning,” on view through January 24; and Mariam Ghani artist talk, Wednesday, November 5, 6 p.m., at BCA Center in Burlington. burlingtoncityarts.org

This article appears in Nov 5-11 2025.