When Rep. Emilie Krasnow (D-South Burlington) arrived in Montpelier in 2023 for her first day in the House, she felt a newcomer’s jitters, although she was hardly new to the building. Her father had served in the legislature when she was a kid, and as a young adult she had worked as an assistant in the Senate and the lieutenant governor’s office.

Jitters aside, she knew she had a network of peers who could provide mentoring and friendship as she began this next chapter. Krasnow took her seat in the company of six women who were fellow graduates of Emerge Vermont, a program that recruits and trains Democratic women to run for office.

“We came in knowing each other, knowing each other’s families,” Krasnow said. “And the support of the group has just never left.”

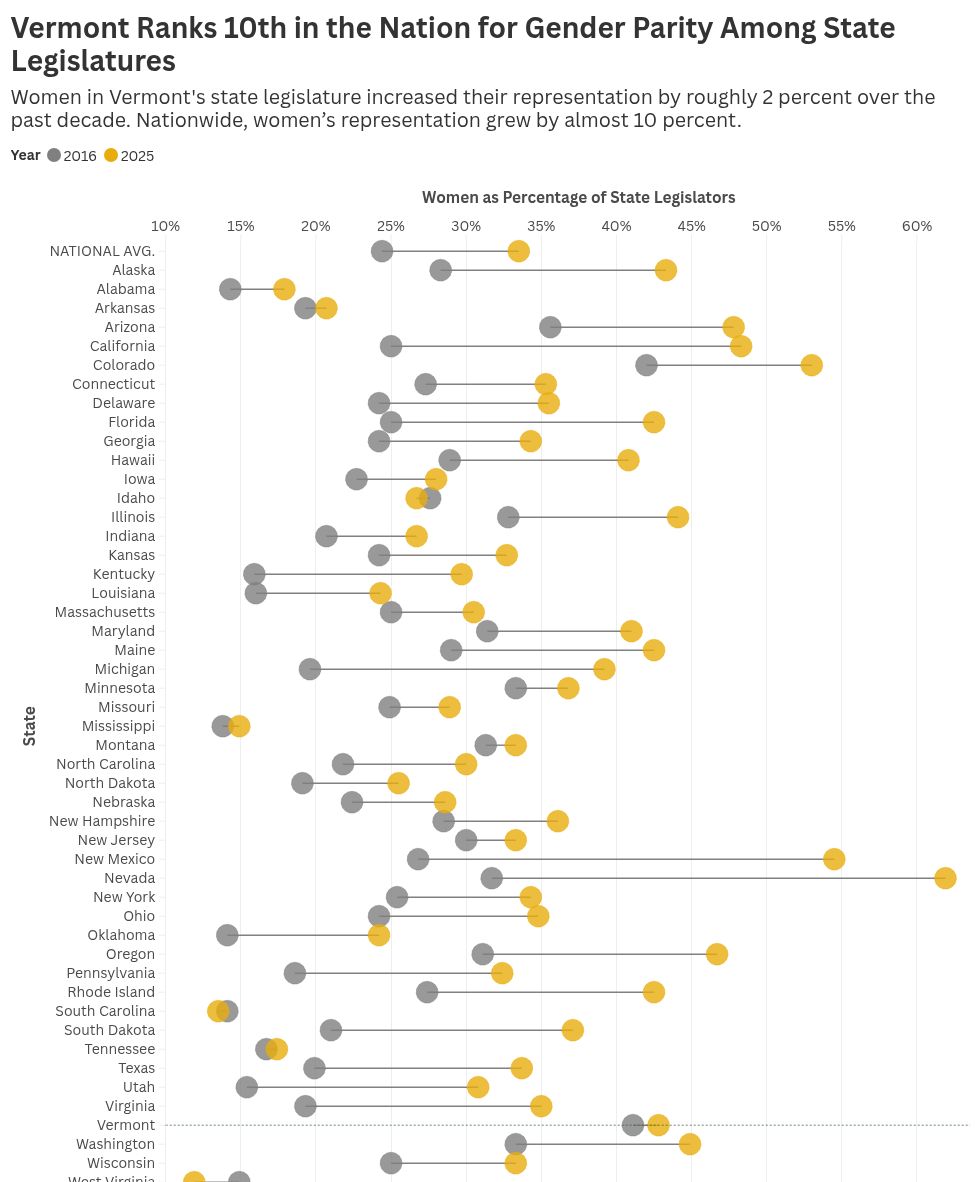

Krasnow is one of 78 women serving in Vermont’s 180-member state legislature this session — a high-water mark for the body as it inches toward gender parity. Women hold roughly two in five seats, a modest increase over the past decade and above the national average.

This session, women chair more than half of the legislature’s 32 standing committees. Several hold leadership positions, including House Speaker Jill Krowinski (D-Burlington), House Minority Leader Pattie McCoy (R-Poultney) and House Majority Leader Lori Houghton (D-Essex Junction).

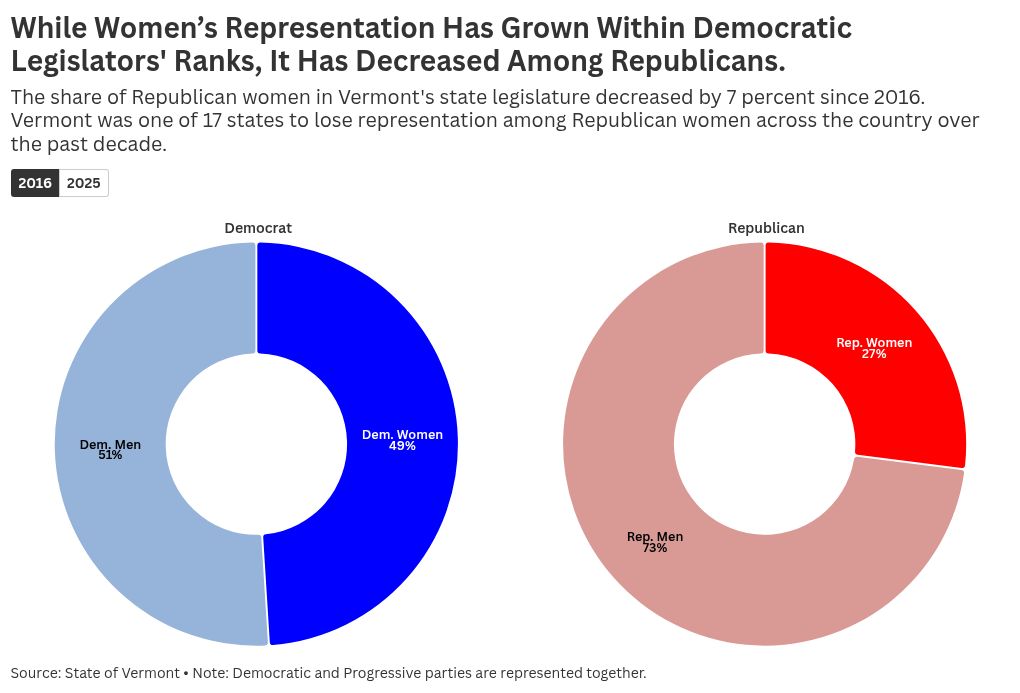

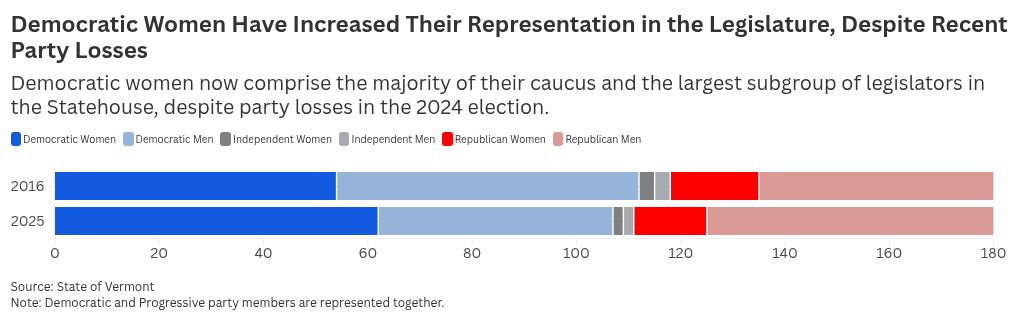

A variety of factors have contributed to this increase, including cultural and political shifts in the status of women. But Emerge can claim part of the credit for launching more Democratic women on political careers. Sixty-two of those 78 women legislators are Democrats or Progressives, making them the largest subgroup of legislators by gender and party. More than half have attended Emerge Vermont trainings; two members, Krowinski and Sen. Ruth Hardy (D-Addison), formerly served as the group’s executive directors.

Emerge graduates are not simply present; they have played a central role in passing landmark policies, including the 2022 constitutional amendment protecting reproductive rights and the 2023 legislation expanding childcare funding. Five of the seven women on the task force currently drafting new proposed school district maps are Emerge trainees.

Emerge’s many graduates also amount to a mentorship network for those who come after them, and they constitute a pipeline of women able to rise through the political ranks: U.S. Rep. Becca Balint (D-Vt.), Vermont Attorney General Charity Clark and Secretary of State Sarah Copeland Hanzas are all graduates of the program.

Meanwhile, the number of Republican women in the legislature has declined. Although the party picked up seats last year in both the Senate and House, there are just 14 women among the 53 Republicans in the House. There have been no GOP women senators since 2018, when the last Republican women members of that chamber chose not to run for reelection. The party has no program like Emerge to recruit, train and support women candidates.

Republican women once were a more prominent presence in the Statehouse. Women have served in the state legislature since 1920, when the 19th Amendment was ratified and Vermont was a resolutely Republican state. The Vermont House elected its first woman speaker, Republican Consuelo Bailey, in 1953. As legislative power shifted toward the Democrats in the late 20th century, women continued to win seats and, more rarely, committee chairmanships.

Democrat Janet Ancel, who worked in the Statehouse as an attorney before being elected to the House in 2004, recalled how some people doubted then-representative Madeleine Kunin’s ability to chair House Appropriations when she became the first woman to do so in 1976. Thirty-five years later, when Ancel became the first woman to chair the equivalent House committee, House Ways and Means, the milestone hardly registered, in large part because women in leadership positions had become so normalized, Ancel said.

“At some point, the fact that you’re a woman ceases to be part of the story,” Ancel said.

Debbie Walsh, director of the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University, said citizen legislatures such as Vermont’s tend to be less professionalized, with lower salaries and fewer staff to assist legislators, and have more open party politics. That leaves space for women to enter and for groups like Emerge to establish a foothold. Emerge America is a nonprofit national political organization with affiliates in 27 states that recruit and train exclusively Democratic women and nonbinary candidates.

Kunin, who served as Vermont’s first and only woman governor, from 1985 until 1991, got the idea to found Emerge Vermont in 2013 after speaking at events for the state chapters of Emerge America in California and Massachusetts. At the time, she had established an informal practice of mentoring and advising Democratic women running for public office. Emerge America and its network of state programs seemed to provide a sustainable, systematic way to share that knowledge, Kunin recalled.

Unlike national groups such as EMILYs List, which endorses and fundraises specifically for abortion-rights candidates, Emerge is strictly an educational and training program. It focuses on teaching its trainees the fundamentals of how to fundraise, canvass, create campaign literature and develop a campaign platform. It also provides opportunities for women to network, practice public speaking and shadow their state legislators at work.

Kunin called on Krowinski and Senate Majority Leader Kesha Ram Hinsdale (D-Chittenden-Southeast), both state representatives at the time, to help establish a chapter in Vermont. The group gathered as an impromptu board of directors. They officially launched Emerge Vermont with a 200-person party in Burlington in September 2013, and the program grew from there, Kunin said.

“Its success has far outpaced anything I thought would happen,” she added.

Part of that success has come about because Emerge has helped women redefine who can serve in the state legislature.

“Men run for office without blinking,” Kunin remarked, noting that women often need to be asked several times or reassured they are qualified before deciding to enter a race.

Jessica Brumsted was one of the program’s early participants. She applied in 2015 while toying with the idea of running for the state Senate. Her previous political experience was behind the scenes, working in the office of U.S. representative and then senator Jim Jeffords in the 1980s.

Once Brumsted was in the training, however, she was encouraged to run for the House seat in her district, even though it meant entering a primary where she was more likely to run head-to-head against an opponent. She said it was still daunting to center herself as a candidate, despite her experience in politics.

“I’d never thought of myself as a person who could do that, and Emerge helped me to see that I could,” Brumsted said. She won her competitive district in Shelburne and St. George and served for four terms before deciding not to run for reelection in 2024.

Seventy of 86 Emerge trainees won their races in the 2024 general election, an 81 percent success rate.

Since Emerge Vermont’s founding in 2013, more than 230 women and nonbinary people have completed the group’s multi-month training program and shorter boot camps. Some attend the training without immediate plans to run, while others pursue local offices. In recent years, the organization has also offered a professional development series for alums only, a municipal boot camp for Town Meeting Day candidates, and occasional one-off trainings on select topics, such as digital and physical security. Each participant must self-certify they are a Democrat, a requirement of all state affiliates of Emerge, despite pressure from across the political spectrum — including program alumnae — to open the program to women of all party affiliations.

Tuition is currently $950 for the group’s 80-hour signature training and $400 for its three-day boot camp. That, along with program fees and sponsorships, funds about 20 percent of the program’s budget. The rest comes primarily from small individual contributors, with additional support from a few major donors, according to Emerge Vermont executive director Elaine Haney, the group’s sole employee. Haney reports to a board of directors based in Vermont and works closely with Emerge America leadership and other state affiliate directors.

Emerge Vermont has enrolled Democrats of all stripes and generations in its recent classes — from progressives to moderates, Gen Z to baby boomers. Not every graduate runs for public office, but those who do most often succeed. Seventy out of 86 Emerge Vermont trainees won their races in the 2024 general election, an 81 percent success rate.

Haney plans to move the training program to years when no state elections are scheduled, partly so participants have more time to prepare their campaigns and also because of the relatively limited pool of potential participants in a small state. Class sizes have varied from 12 to 29 people. Applications temporarily spiked after Hillary Clinton and Kamala Harris lost their respective presidential bids. Haney blamed the rising incivility of politics for the drop in applicants for Emerge training, saying it has made some women think twice before deciding to run for office.

Rep. Alice Emmons (D-Springfield), now in her 43rd year in the House, attributes part of the increase in women’s representation over the past decade to Emerge Vermont. When Emmons was first elected to the legislature in 1983, she was one of 27 women serving in the House.

But as Emerge Vermont has helped boost the number of Democratic women in the legislature, Emmons worries it has also encouraged a more activist mindset, with more lawmakers eager to move fast on the issues that inspired them to run while being less open to compromise.

“Once you get into a legislative position, you have to make a shift into governing,” Emmons said. “And it’s a very different mode of operating than being an activist.”

Krowinski, who was Emerge Vermont’s executive director from 2019 until 2021, when she was first elected House Speaker, pushed back against the narrative that Emerge had brought about a new era of activist legislators. Many people, regardless of party, are inspired to run by an issue facing them or their community, she said, and then take on larger questions as legislators.

While Haney would like to add a detailed unit on parliamentary procedure, she doesn’t have the budget to expand the curriculum, and it largely falls outside the program’s scope.

“They don’t need me to tell them how to do their job,” she said. “What they need me to do is help them get to their job.”

Haney said she had heard these critiques from others, including men. But she views the drive and determination of Emerge candidates — and their eagerness to make change — as a strength, not a liability.

“It may bump up against, let’s be honest, some of the men in the legislature who are not either used to or don’t like having strong, opinionated women in their committee rooms taking stands on issues that are important to them,” Haney said.

“Politics is still very much a man’s world.”

Rep. Emilie Krasnow

Krasnow, the representative from South Burlington, confirmed that she has encountered sexism in the Statehouse and on the campaign trail.

“Politics is still very much a man’s world,” she said. “As a younger legislator, I still get called by constituents, ‘Sweetie,’ ‘Honey.’”

The support and guidance she’s found through Emerge has helped her navigate the moments when she has felt unsafe or upset, she said.

Senate Majority Leader Ram Hinsdale said the program also provides a forum for women to have difficult but supportive conversations about issues they face on the campaign trail, such as harassment and cyber abuse.

“We don’t have a magical solution, but we do have a lot of community and a lot of easier ways for people to find help and break isolation than we did before,” Ram Hinsdale said.

Some Republican women legislators say they have lacked that support. Rep. Carolyn Branagan (R-Georgia), who recently returned to the House after moving to the Senate for a time, said it’s been challenging to navigate campaigning and legislating with relatively little support from the Republican establishment. When she first ran for the House in 2002, she did not have a mentor and received little financial assistance or training from the Vermont Republican Party.

“You learn on your own, because there’s no one there to help you,” Branagan said.

Branagan said it has been “thrilling” to see women speak with more confidence on the House and Senate floors over the years. She applauded Emerge for equipping its trainees, especially the younger candidates, with the tools needed to succeed on the campaign trail.

She said she explored creating a similar initiative with the Vermont Republican Party after she was elected to the Senate in 2016, but state and county leaders showed little interest.

House Minority Leader McCoy said several women approached her earlier this month to see if she would help set up a training program for potential Republican women candidates. McCoy welcomes the idea of a Republican counterpart to Emerge in some format and said she would work with the women who proposed it to explore developing a program.

It was not immediately clear how a Republican effort might be orchestrated or funded in Vermont. Nationally, no Republican counterpart provides the same training and support as Emerge, said Walsh, the Rutgers political scientist. Her research has found the discrepancy is fueled in part by the two parties’ differing ideologies around identity politics.

“The Democratic Party embraces the concept that diversity in your officeholders, in gender and race and ethnicity, is substantively important,” Walsh said, whereas the GOP is more likely to trust that the best candidate will rise to the top.

John Killacky, a former Democratic state legislator who represented South Burlington for two terms starting in 2019, sees Emerge’s success as a model for other groups, not just political parties. A program like Emerge democratizes institutions, he said.

“It takes people who are interested in civic service, gives them permission and allows them to see themselves as viable leaders,” Killacky said. He and two lawmakers are developing a similar program at the Vermont Arts Council to encourage artists to run for office.

Krasnow said she sees programs such as Emerge as helping all parties. There’s no reason that the Republican party or others couldn’t or shouldn’t launch their own initiatives, she said, especially if parties say they want more women to run.

“It’s like, ‘Well, what’s stopping you?’” she asked.

The original print version of this article was headlined “Womanning Up | Emerge Vermont is one reason there are so many women in the legislature. Some GOP members say their party needs a similar group.

Correction, October 29, 2025: An earlier version of this story misreported how many terms Jessica Brumsted served in the Vermont House.

This article appears in Oct 29 – Nov 4 2025.