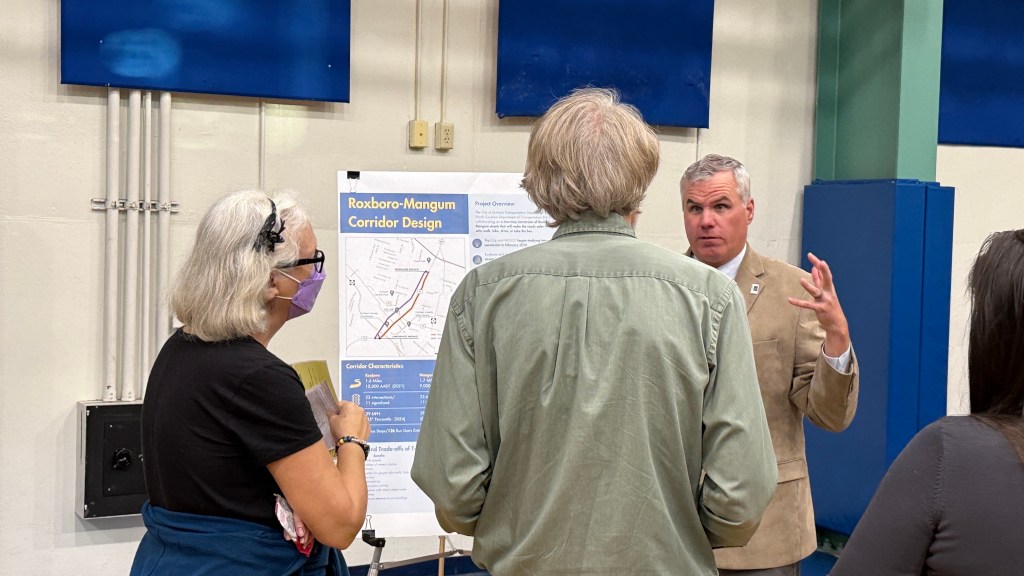

Residents got a first look at possible designs for making Roxboro and Mangum streets in Durham two-way at an open house this week.

The design concepts’ debut a big step forward in addressing two dangerous streets in Durham, and one of transit advocates’ top priority projects for reducing road deaths and injuries.

The Roxboro Street portion of the project stretches from Lakewood Avenue on the south side of downtown to Highway I-85 on the north end. The Mangum Street portion also starts at Lakewood but ends at Markham Avenue. Construction is expected to begin in 2027. This year’s budget includes $1.2 million from the city’s Capital Improvement Plan to move forward on the design process, but total costs are still unclear (traffic lights can cost hundreds of thousands per signal, and other material costs could fluctuate based on tariffs and other national trends.)

Based on the designs shared at the open house Tuesday, reconfiguring Roxboro and Mangum wouldn’t require a ton of major construction. Large design renderings showed two-way traffic patterns, intersection redesigns with new stoplights to help control speeds, and curb adjustments for essential vehicles like fire trucks and buses. Attendees used sticky notes to leave comments or suggestions like “protected bike lanes” and “roundabouts.”

Attendees at the open house pointed out key areas like the downtown Durham library where five lanes of one-way traffic make it challenging for some residents to cross the wide intersection quickly and safely. Overall, folks who attended the open house said the two-way conversion seemed “simple” and a “no-brainer.”

But while converting to two-way could reduce speeds and provide additional safety, advocates continue to push Durham transportation department and the North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT), which owns the roads, to include more bike and pedestrian infrastructure within the reconstruction project.

“I think [the designs] are a minimal improvement at best,” says Scott Mathess, a Durham resident and avid cyclist who co-organizes the school “bike train” group ride in his neighborhood. “I don’t think it’s going to make things easier for pedestrians or cyclists downtown. It doesn’t add anything to bike infrastructure. It doesn’t add anything to pedestrian infrastructure.”

Converting both roads back to two-way routes would be a return to Durham before urban renewal cleaved Hayti from downtown, like the program did in cities nationwide in the 1950s and 1960s. A hundred years ago, not only could you drive in both directions up and down Mangum Street, but Durhamites could catch a street car bustling through the middle of the road.

The sections of Roxboro and Mangum that would be reworked still cut through the heart of downtown Durham, but in the last two decades, residential homes have proliferated along most of the route. Some have staked signs in their yard that read, “slow down” or “children at play.” Safety is a major concern for residents along the corridor, particularly for families of young children who are terrified by the breakneck speeds of cars whizzing by in the 35 mile-per-hour zone.

A traffic analysis study of the project area prepared for the city showed that between 2018 and 2023, Roxboro Street incurred 748 total crashes, while Mangum Street saw 434 crashes. Only a small percentage of crashes involved pedestrians and cyclists, but that could be due to a low volume of travelers along the corridor using those methods due to safety concerns. The study also suggested that two-way conversion would “result in an overall acceptable level of service at all the study intersections” even during peak traffic hours.

Advocates say corridors like Roxboro and Mangum, and the nearby Duke Street and Gregson Street one-way pairing, are dangerous for pedestrians and motorists alike. John Tallmadge, executive director of Bike Durham, views the Roxboro-Mangum project as a symbol of Durham’s commitment to reaching its goals for Vision Zero, a multinational movement to reduce traffic deaths and serious injuries.

“Roxboro Mangum is really a test case for whether there’s a commitment to make physical design changes to some of our busier, dangerous streets,” Tallmadge told the INDY in May during Bike Month. “It feels like if they back away from this project, we don’t have a lot of confidence that they’ll take on the other projects. They’re all going to be hard. They’re all going to be bigger dollar projects. So we think it’s important they see that through.”

Durham will ultimately need sign off from NCDOT before any construction begins. The state passed its own Vision Zero resolution a decade ago, and in its most recent strategic plan, NCDOT laid out key metrics for meeting its Vision Zero goals: 50 percent reduction in the number of fatalities on public roadways by 2035, and 100 percent by 2050. Transportation advocates like Mathess and Tallmadge say the state should allow local municipalities like Durham to pursue major road reconfigurations if they are serious about hitting the mark on Vision Zero.

As Durham continues to prioritize density and sustainability inside the urban core, city transportation and planning staff, as well as transportation advocates, are pushing ways to de-emphasize single occupancy vehicles in favor of public transit, biking and walking. In larger cities, teens and young adults forego a driver’s license because other transportation options are easier and more accessible. Mathess says that his daughter and her friends are continuing that trend even in places like Durham, and that local officials should take note and plan for future generations.

“Up to now, we’ve been building a city for Boomer culture and our grandparents and their parents,” Mathess says. “What we need to do is start rebuilding the city for our children and their children. Our children don’t want to drive everywhere. We need to start working on cities that are safe to walk, safe to bike, and laid out for public transit. Individual personal automobiles are on their way out, yet we continue to try to build for them, and that is a mistake. Now is the time. I mean, 20 years ago was the better time, but right now is the next best time.”

The conversion of Roxboro and Mangum isn’t the only corridor being considered for a redesign. Public engagement is currently underway for Duke Street and Gregson Street, another state-owned one-way pair where many injuries occur. The city is also looking at updating traffic patterns on a number of state- and city-owned roadways when those roads are resurfaced and repainted throughout the next year. During the resurfacing process, the transportation department could choose to paint in a new bike lane or other markings that don’t require additional construction, saving money while also moving towards larger transportation goals.

“We’re trying to move things along with urgency, but we are working within NCDOT’s parameters and essentially trying to bring them along with us,” says Lauren Grove, Durham’s Vision Zero coordinator. “It sets a precedent for other conversions or other state-owned roads and how we address safety improvements on some of those bigger arterials, like on Duke and Gregson, like Holloway and Fayetteville where we’re hoping to turn those into transit emphasis corridors and make improvements. All of these are state-owned roads, and so we’re really trying to make improvements in a system that we don’t really have the ultimate say in.”

Follow Reporter Justin Laidlaw on X or send an email to [email protected]. Comment on this story at [email protected].