Henry David Thoreau was big on taking walks—or “sauntering,” the word he once used in a lecture on the subject. In that lecture, the writer and philosopher asserted that he couldn’t feel well unless he sauntered for at least four hours a day.

It was on those long walks around Concord, Massachusetts, that Thoreau collected hundreds of botanical specimens, which he then brought home to press, scribbling down notes about where and when each plant was collected. Now, 648 of those preserved specimens are housed and digitized in the Harvard University Herbaria.

But while those specimens from Concord made it to this century in preserved form, many of the actual plants didn’t survive: an estimated 30 percent of the species from Thoreau’s records have gone “locally extinct,” according to the museum, with another 35 percent “close to the same fate.”

In Search of Thoreau’s Flowers: An Exploration of Change and Loss, currently on view at NC State University’s Gregg Museum of Art & Design, draws on that digitized collection in a small but expansive-feeling exhibit that contends with the loss of biodiversity. Originally mounted at the Harvard Museum of Natural History, the exhibit represents the joint scholarship of Marsha Gordon, Robin Vuchnich, Leah Sobsey, and Emily Meineke, an effort that marries science, art, and the humanities. This iteration of the exhibit, which expands on the original by tying in North Carolina flora and fauna, opened in September and runs through January 31, 2026.

On a recent museum visit, Gordon, an artist and a professor of film studies at NC State, walked me through the exhibit.

“We want people to feel a sense of beauty and awe,” she explains, standing outside the Black-Sanderson Gallery, which anchors the exhibit.

“Definitely awe,” a museum visitor interjects, coming out of the gallery. She nods at me: “You’ll see.”

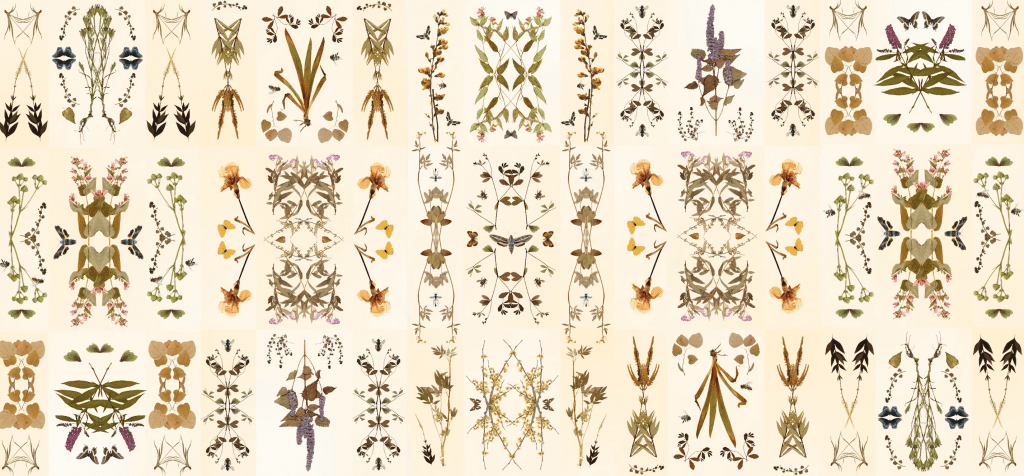

About half of the exhibit is housed in the lobby we’re standing in. To Gordon’s right is a digital mosaic she created with Vuchnich, who is an adjunct lecturer in NC State’s College of Design. Named “Herbaria North Caroliniana,” the work spans five windows and features images from NC State’s vascular herbarium alongside photographs of pollinating insects from the university’s research collections. Plants and insects are arranged in delicate patterns, creating mosaic-like designs you might see through the end of a kaleidoscope.

In front of us, in the lobby, an eye-catching blue swoop over the gallery door compels us inward. This is artist Sobsey’s “Swarm: The Blue of Distance,” an installation of once common North Carolina insects—the giant silk moth, the rusty patched bumblebee, and more—that are now endangered or locally extinct.

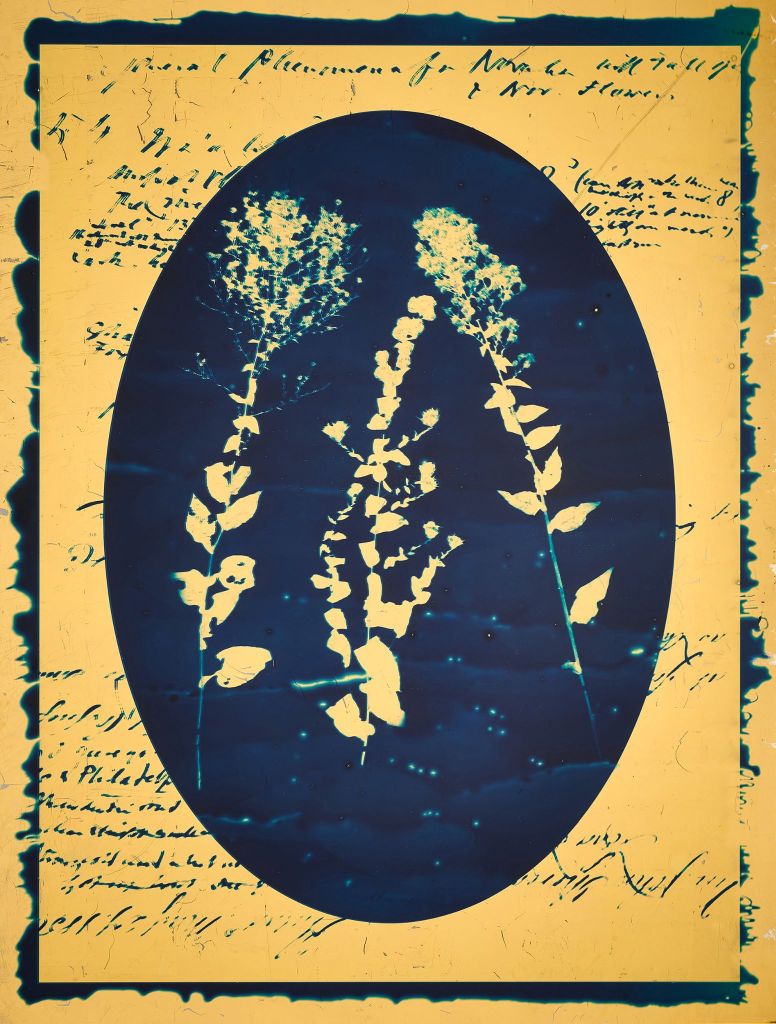

Sobsey, an associate professor of photography at UNC Greensboro, incorporated specimens from NC State’s collections, representing regions from all across the state. She created the installation using cyanotype—a sun-printing technique discovered in 1842 that produces Prussian-blue images, and a throughline through the exhibit.

To the right of the gallery door is another cyanotype, this one an image of the oldest longleaf pine in North Carolina, which is located near Southern Pines and estimated to be 477 years old. Like the insects darting toward it, this Southern lodestar is also in danger: Longleaf savannas, some of the richest ecosystems in the world, now occupy less than 3 percent of the original 90 million acres of forest the trees once sprawled across.

“There’s this way of thinking about plant invisibility, you know—we don’t really think about plants in the same way that we do with animal loss,” Sobsey says.

Is it depressing to see renderings of species we’ve driven out with deforestation, pollution, pesticide use, and a hundred other facets of modern life? Absolutely. Global insect populations are in a free fall, with a 2019 study determining that 40 percent of insect species are in decline, with the rate of species decline topping out at 2.5 percent a year.

But while In Search of Thoreau’s Flowers contends with this profound loss, it doesn’t fail to offer museum visitors ideas for a way forward. An adjoining exhibit, The House of Ideas: Plants in Art, offers practical local tips. These come from Meineke, an assistant professor of urban landscape entomology at the University of California, Davis: Let trees live as long as possible. Plant a pollinator garden. Let bees live on your property.

“This came together from four friends, really,” Gordon says. “We were trying to think through something we could do around questions of climate change and the environment—thinking about it in a way that is realistic about what is happening in our country and all over the world, but also not to be so doom and gloom that people shut off.”

Thoreau’s Walden, a staple of high school curricula, has inspired generations of nature lovers. Sure, the proto-libertarian philosopher had his shortcomings: he was a bit of a misanthrope, one who outsourced laundry to his mother two miles away from his famous cabin, all while preaching strident individualism.

Still, finer points of his writings remain evergreen: the call to cherish public lands, to “live deliberately” and simply, to cultivate curiosity about your own small corner of the world. And, as In Search of Thoreau’s Flowers demonstrates, the writer was ahead of his time as a naturalist. Walden was his Eden.

Thanks to Thoreau and other area naturalists, the ecosystem of Concord—which author Henry James once called “the biggest little place in America,” due to its historical import—has been documented across centuries. That record formed a portrait of the biological impacts of climate change. In Walden Warming, the botanist Richard Primack observes that Thoreau’s archives helped scientists determine that local plants were now flowering weeks earlier than they were 160 years ago.

“Thoreau was doing early climate research,” Sobsey explains. “He kept detailed notes about when things were flowering, and that’s the data set that now they’re looking at, in terms of how things have changed.”

Sobsey has worked with 19th-century herbaria before: Emily Dickinson, it turns out, was also a devout botanist who left behind 400 pressed plants.

Sobsey says the two writers had different styles: Dickinson’s pressings were “beautiful and pristine,” like her poems, while Thoreau’s were a bit more hectic. Considered together, though, it’s hard not to be inspired by the ways preservation work can deepen a relationship with the natural world.

Inside the Black-Sanderson Gallery, Vuchnich’s data visualizations of Thoreau’s plant archive are mapped across three walls. One wall features a quilt-like image of the herbarium, with extinct plants coded blue; another wall is an immersive visualization of colorful, endangered plants that hover over Walden Pond.

When the gallery is empty, the flowers grow across the screen; when a visitor steps into an interactive circle in the middle of the space, the flowers, in turn, react—dancing, dispersing, and reassembling.

While this might seem like an indictment of human presence, the effect is more nuanced: The show’s general thrust is a gentle reminder that we coexist with the natural world and bear a dependence on, and responsibility to, it that can be joyfully responsive. The gallery projections would be an animating space for kids to move around in; conversely, a few cushions along the wall are an invitation to sit and reflect as soundscapes recorded at Walden Pond fill the room.

In Search of Thoreau’s Flowers has a small museum footprint, but its structure is designed for exploring, maybe even sauntering. On your way out of the gallery, linger at Sobsey’s cyanotypes of Thoreau’s plant pressings, transposed against his tangled handwriting and gilded with 23-karat gold leaf. These “plant portraits,” as Sobsey calls them, have reflective surfaces where, when you lean in, your own face will appear: another reminder of our inextricable relationship with nature.

Finally, don’t leave before visiting the museum’s pollinator garden, immediately adjacent to the lobby. While blooms are quiet this time of year, the garden is an active reminder that it is possible to cultivate your own small corner of the world and make it better. After all, Thoreau’s walks—and the plants he collected on them—are still creating powerful ripple effects, 160-some years later.

Follow Culture Editor Sarah Edwards on Bluesky or email [email protected].