Police Sgt. Paul Locke had no particular destination. He was simply driving where his mind led him, the way he had spent thousands of hours patrolling the town of Milton over the past 25 years, with only the patter of disc jockeys and squawk of his police radio for company.

But when he stopped at the intersection of Railroad and Main on this windy April evening, something caught his attention: tendrils of smoke snaking like an SOS into the sky.

To report this story, Seven Days reviewed more than 50 police reports, along with hundreds of pages of documents recovered from Aaron LaRoche’s apartment, and interviewed several people who knew him.

Locke, 48, pulled to the side of the road and looked up at the second-story window. He knew the unit well — by now, all the cops in Milton did. Inside lived a 38-year-old recluse whom police had tried to coax into receiving psychiatric treatment on more than a dozen occasions. The man always refused. To avoid aggravating the situation, officers always backed away.

Now something there was on fire, and Locke feared the worst. He radioed for backup, then climbed the wooden stairs that led to the man’s porch and knocked.

“Aaron, it’s police!” he said. “Your house is on fire! You’ve got to come out!”

Over the next four hours, the situation would escalate into a full-blown crisis that would leave one man dead and another wounded. It would offer a fresh reminder of the potential consequences of leaving mental health issues untreated for so long that they show up in ways demanding a response from police officers — even familiar ones, desperate to help.

The changes were gradual at first — the odd facial expression or curious comment. But by summer 2020, Real LaRoche had come to recognize that something was seriously wrong with his son.

Gone was the affable and outgoing Aaron, who once enjoyed long summer days trout fishing with his father. As an adult, he had trained his wiry body in dance classes and earned a black belt in karate. Now he was distant and withdrawn.

After living in Colorado for a year, Aaron had moved back in with his parents in Winooski in late 2019 and had taken to walking around the house in a zombielike trance. Real would catch him shaking his head at times, as if disagreeing with some unseen person.

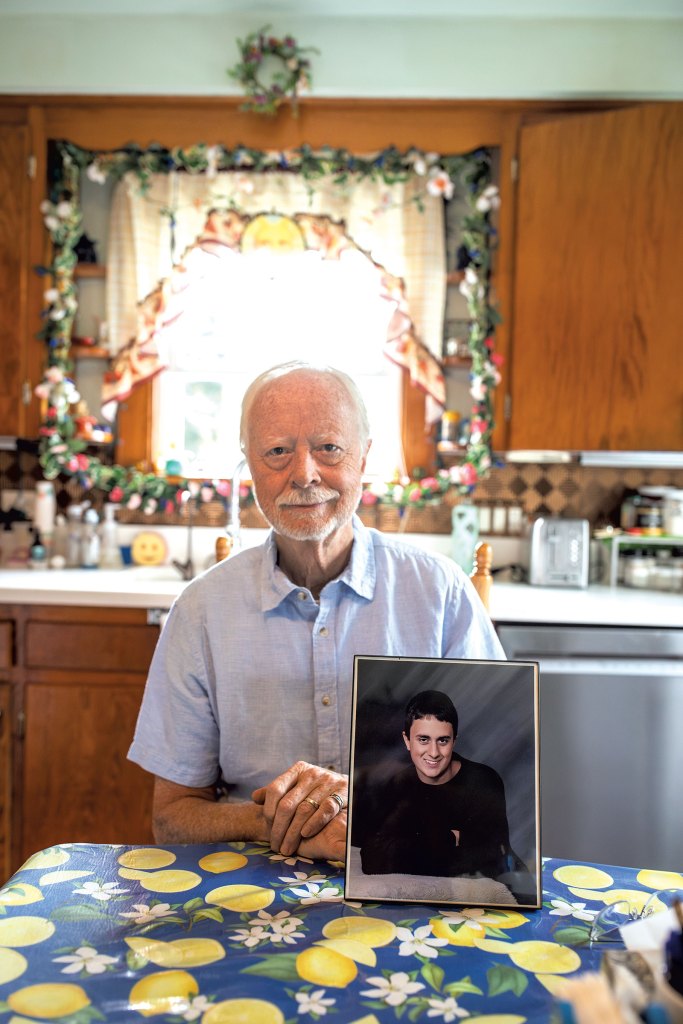

Real, 72 and rail-thin, with wispy white hair, had retired early from a career at IBM, later GlobalFoundries, to help care for his chronically ill wife, Julie. His caregiving duties made it difficult to keep close tabs on Aaron, their youngest son. He was also careful not to pry. So he left Aaron alone, believing that his son, his best friend, would eventually confide in him.

Real was encouraged that fall when Aaron announced that he had found an apartment. The father grew more hopeful still the following year when Aaron began dating a woman he had met at Walmart through their COVID masks.

But soon after, Aaron’s demeanor began to darken. Over many months, he avoided weekly hangouts with his older brother, Ryan, and showed up to family gatherings subdued or agitated. He got into vicious political arguments with strangers online.

Finally, in summer 2023, Aaron told his parents he had been hearing menacing voices and experiencing visions of torture. “Just evil, evil stuff,” Real recalled.

Mental health experts agree that catching someone in the early stages of a psychotic break can prevent them from spiraling into catastrophe. But the LaRoches were skeptical of mainstream medicine. They feared that Aaron would land in some “mental health gulag” for the rest of his life, Real said. So they set out to find a spiritual “healer” who could help Aaron address his problems.

Before they could schedule the first session, Aaron shut himself away from the world.

A note he typed on his computer in August 2023, following what would be his final visit to his parents’ house, reflected increasingly delusional paranoia. He believed his mother was moving abnormally and thought his father was talking strangely, “as if speaking with an AI bot.”

A few days later, Aaron asked Real to pick up groceries for him. When his father arrived in Milton to deliver them, Aaron declined to let him inside.

“I’m not well,” he told his father through the door.

“What’s the matter?” Real asked.

“I’m too afraid,” Aaron responded.

Real returned to his car and drove home, crying the entire way.

Sgt. Locke, whose boyish, goateed face belies his long years as a cop, watched with growing dismay as the smoke rose from Aaron’s apartment. Firefighters had arrived within 10 minutes and determined they needed to get inside. One of Aaron’s neighbors called the building owner, Fay Pelletier, who drove over.

Pelletier, who is in his late sixties, took ownership of the three small apartment buildings at 74-78 Main Street years ago from his parents. Aaron was one of six tenants there and lived in a two-bedroom unit on the second floor, accessible by a set of wooden stairs in the back.

Pelletier had grown fond of Aaron, whose remote job at an international solar company provided him a healthy income that allowed him to pay his rent months in advance.

The two spoke occasionally on the phone and exchanged best wishes by text over the holidays.

There were occasions when Aaron wouldn’t let Pelletier into his apartment, but the landlord still had a soft spot for his tenant and was deeply worried about his safety. With police and firefighters on the scene, he sent an urgent text asking Aaron to call him.

“It’s very important,” Pelletier wrote.

“Complain to the police station,” Aaron responded. “I am under mind control.”

“You need to open up the door they’re gonna kick the door in because the smoke,” Pelletier wrote.

Aaron replied: “I’ll kill them.”

The first “healer,” who practiced something called the “Mace Energy Method,” met with Aaron over Zoom for only a few months. The man, Eric Mace, informed Aaron’s parents that their son wasn’t committed enough to the process.

Undeterred, the LaRoches turned to a former paramedic named Anthony Mowery, who ran a mental health business out of a ranch in Tennessee.

Mowery described himself as a practitioner of “quantum healing,” a pseudoscientific approach that promotes wellness through the principles of quantum physics. Popularized by alternative medicine guru Deepak Chopra, the method claims that people can overcome mental and physical pain by intentionally shifting internal energies.

Mowery told Aaron’s desperate parents that he could help dispel the voices in their son’s head through hours-long virtual sessions involving hypnosis and tuning forks. The two met throughout winter 2023, and, for a time, Aaron seemed engaged, his father said.

Then he started to miss appointments, and before long, he was refusing to see Mowery at all. (Mowery did not respond to a request for comment.)

By this point, Aaron was convinced that the key to banishing the internal voices wasn’t treatment but figuring out who was speaking.

His unpredictable behavior had cost him his job, and so he spent his days scouring the web for information. He printed pages from news and government websites, highlighting certain words as if in search of hidden, deeper messages. He fed his hypotheses into AI chatbots and meticulously documented his symptoms. He compiled all of his findings in a 30-page document that he titled “Adversarial Harrowing” and sent it by email to Milton police, urging them to investigate.

He called the department a few weeks later and spoke with an officer who gently told him that the only way to quiet the voices would be to see a doctor. Aaron found the suggestion offensive. I am not sick, he responded. I am being attacked.

What don’t you understand?

Locke sighed as Pelletier, the landlord, described Aaron’s threat to shoot firefighters. Then the sergeant asked everyone to step away from the porch while he considered his options.

It wasn’t the first time Aaron had threatened violence. But the warnings had always been in the abstract, and there was no evidence he owned guns. His father didn’t think so, and Aaron had consistently denied having any.

Locke’s few semi-coherent conversations with Aaron had been respectful, and the officer didn’t believe he would hurt anyone. The sergeant wasn’t about to wager a life on it, though, so he hastily made a plan: Police would remove Aaron from the apartment so that firefighters could put out the source of smoke before it threatened neighboring homes.

Locke recruited two other officers for the job. The men geared up, then headed toward the stairs.

After Aaron emailed police his 30-page report last summer, the Milton department began receiving calls from neighbors who could hear him screaming about torture and from old friends disturbed by his increasingly erratic social media postings. Aaron started calling, too, to inquire about the status of the investigation he had requested or simply to scream and mutter before hanging up.

His physical appearance began changing as well. On video calls with his parents, he appeared exhausted and disheveled, his neatly cropped brown hair grown into a shaggy mop.

Real had come to accept that Aaron needed medical attention. But his wife Julie’s health was worsening, and he barely had enough time anymore to deliver Aaron’s groceries each week, much less figure out how to persuade his son to accept help.

Last fall, the state’s mental health system got involved. Aaron’s growing number of police interactions prompted outreach workers at Howard Center to conclude that he was incapable of making informed decisions about his care. They persuaded a judge to issue what is known as a mental health warrant, which would allow police to take him to the hospital to be evaluated, whether or not he was willing.

Some 500 mental health warrants have been issued in Vermont over the past two years, and all but a handful were carried out without issue. But Aaron’s case posed a unique challenge.

Although judges have the power to grant police officers permission to forcefully enter a home to take someone into custody, they can be reluctant to exercise it, given the risks involved. And because a person’s state of mind can yo-yo, mental health warrants in Vermont expire after 72 hours.

That gave Milton officers only a brief window to convince Aaron to leave his home voluntarily. The judge had not agreed to let them enter the apartment otherwise.

When police arrived on October 8, with mental health workers in tow, Aaron agreed to speak through his window. He appeared responsive and polite, though he would close the window shade at times to scream, then open it up again and apologize.

But he refused to open the door and insisted that he did not pose a threat to himself or anyone else. Police tried to serve the warrant again the following day, with similar results, and it expired soon after.

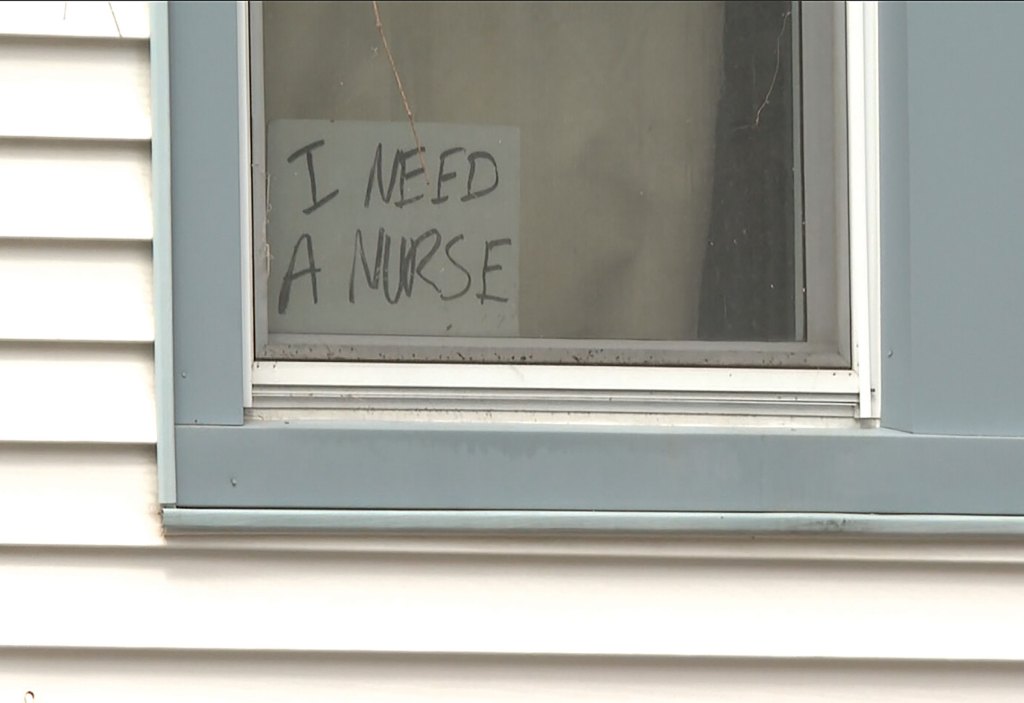

A pattern would emerge over the following months: Aaron would call or text the police station 10, 20, even 30 times a day, then refuse to open the door when Locke and other officers arrived. Police found themselves engaged in an Excalibur-like challenge to coax him from the apartment. No matter how much they cajoled or pleaded, Aaron wouldn’t budge.

Police officers showed up one day to find handwritten signs in the windows that read “mind control” and “I need a nurse.” Aaron’s social media posts became increasingly unhinged. The voices in his head — which he said included those of Celine Dion and the girlfriend he had met at Walmart, who eventually filed a restraining order against him — began telling him to shoot himself.

Then, in February, Aaron posted online that the voices were encouraging him to “seek a lethal weapon” so that he could “go on a mass shooting and kill kids.”

That post prompted an alert to the Milton Town School District and more visits from authorities.

It also led to a second mental health warrant. In an affidavit in support of this latest request, an outreach worker wrote that Aaron did not seem to understand that he was experiencing the effects of mental illness.

“I fear that if he does not receive treatment, his psychosis will continue and he may cause serious harm or death to others in his community,” said the affidavit, which was quoted in a police report.

The warrant was granted. Again, Aaron refused to answer the door, and again, police decided they had no justification to force their way in. Aaron’s comments, while frightening, did not contain a specific threat toward any specific person or place. And he continued to deny that he owned firearms.

Aaron emailed police the following morning to request that officers call or email if they wished to speak with him again.

“I believe I have the right to manage my condition, and I often feel I have more knowledge about it than others,” he wrote. “To achieve effective collaboration, I cannot engage in a process that feels hostile or punitive, especially concerning a condition I am already managing.”

Frustrated, police began to build a criminal case for disorderly conduct related to Aaron’s online posts and incessant phone calls. But they were discouraged by local prosecutors, who argued that citing Aaron with a misdemeanor would not get him the treatment he needed. Deputy State’s Attorney Sally Adams suggested that officers instead seek a third mental health warrant — this time with an added stipulation that they could forcibly enter his home.

Barely 20 minutes had passed since Locke noticed the smoke on April 23, 2025. Now two officers — one carrying a shield, the other wielding a sledgehammer — bracketed Aaron’s door, and the sergeant stood beside them, waiting to give the go-ahead.

Locke had forced his way into homes to arrest people accused of violence or selling drugs. He had learned that those situations were somehow easier to prepare for mentally, because when you go in expecting danger, you’re ready when it finds you.

This was different. Locke didn’t want to arrest Aaron. He was there to help. Although Locke expected some resistance, he believed that the situation would end peacefully — and, with any luck, get Aaron to the hospital.

A swing of the sledgehammer splintered Aaron’s door with a loud bang. But the door barely opened and wouldn’t budge when the officer struck it again. It was barricaded from the inside. The police would need another way in.

That’s when a figure appeared in the doorway, and Locke realized he was staring down the barrel of a gun.

A month earlier, Milton police had decided not to pursue the local prosecutor’s recommendation of breaking into the apartment by force to get Aaron to see a doctor. Instead officers spent March and April trying to convince him to leave of his own accord — or, at the very least, to quit tying up their phone lines.

Their reluctance to employ force was understandable. In recent years, law enforcement officers in Vermont have been repeatedly accused of mishandling cases involving people in distress. Some officers were criminally charged. That’s why many departments, including Milton’s, now work closely with trained mental health providers to try to de-escalate sticky situations.

But in Aaron’s case, even the professionals at Howard Center were throwing up their hands. They were wary of going to his apartment unless there was a true emergency.

Aaron’s behavior deteriorated further in early March after his mother, Julie, died from a stroke. His phone calls to the police department became incessant. One night, he left 20 voicemails, each of which staffers had to listen to, in case one contained something important. During one police visit, he threw bananas off his porch in a fit of rage and berated mental health workers.

Then, on April 22, a rare glimmer of hope: Aaron texted 911 to say he needed an ambulance. Perhaps this was the chance to get him help. But when Locke drove over to the apartment, Aaron refused to come outside.

A day later, he placed a wad of dollar bills into a bowl and lit it on fire inside his apartment. It sent wispy fingers of smoke into the air above Railroad and Main.

The first bullet caught Locke in the vest. The second hit him in the lower back as he spun away. A third missed.

The shock of pain mixed with Locke’s disbelief that Aaron had pulled the trigger. The wounded officer rose to his feet and wobbled down the stairs as the officer with the riot shield shoved it in the doorway to cover his escape.

Locke mentally assessed his injuries and determined he would survive. The bullet had gone straight through his back and out the front of his hip. But his mind raced as he was hoisted into the ambulance.

He worried the third bullet might have caught someone on the ground. (It didn’t.) His next thought was of his wife, who would soon receive the phone call every law enforcement spouse dreads.

He wanted the next voice she heard to be his, so Locke grabbed his cellphone while EMTs worked to stop his bleeding. He told his wife to meet him at the hospital with fresh clothes.

Don’t drive too fast, he said: “I’m going to be OK.”

After shooting Locke, Aaron retreated into his apartment, and the other officers took cover.

Aaron’s violent reaction had given police all the justification they needed to use deadly force. But they held out hope for a different ending and, over the next few hours, attempted to talk Aaron into surrendering.

At times he appeared in the window to survey the army of police vehicles that had descended on his street. Among them: the Vermont State Police tactical team, which had assumed control of the crisis.

Pelletier called Real and described what had happened.

Real couldn’t stomach the idea of standing outside his son’s apartment waiting for a resolution. So he stayed at home in Winooski, where a police officer sat with him as the standoff dragged on.

At 10:48 p.m., Aaron texted his father. “They were breaking in, I was in fear for my life,” he wrote.

“They will not hurt you,” Real responded. “You did some damage. You’re on the news. Please let these people help you.”

Police had decided by then that they needed a better idea of what awaited them inside Aaron’s apartment. So they tossed in several flash-bang devices, then flew a small drone equipped with a camera through the entryway.

The drone’s camera found Aaron in the bathroom, lying in a pool of blood. He had shot himself in the head.

The voices were finally quiet.

Six months later, Locke’s career is in doubt. The bullet that pierced his hip caused lasting nerve damage, and he’s confined to part-time, light desk duty while doctors try to determine whether he’ll ever get back on the road.

He could retire tomorrow with full benefits. But being a cop is how he understands his place in the world, he said during an interview, and he would prefer to go out on his own terms.

Locke’s scars aren’t only physical. He can’t bear to read the investigative reports from the shooting or watch his body camera footage. The veteran officer hasn’t even worn his uniform since that day. He has met with a therapist who specializes in working with first responders. But Aaron’s death weighs on him.

A tattoo on Locke’s forearm now memorializes the day he was shot. Beneath the date is a sword with wings representing Saint Michael the Archangel, who is considered a spiritual warrior and protector. “I think he was looking over me,” Locke said.

Cleaning out Aaron’s apartment, Real and his older son found thousands of pages of documents Aaron had amassed during his period of isolation. Among them was what appeared to be an undated, handwritten receipt confirming the purchase of two handguns from a private seller.

Evidence of Aaron’s distress lingered weeks later when Pelletier asked his usual handyman to stop by the apartment. Aaron had plastered the walls with stickers containing cryptic scrawls. When Pelletier drove the handyman home, the worker said he wouldn’t return the following morning.

“It’s too much for me,” he told Pelletier. “This guy was really hurting.”

Real does not blame the police for what happened. Yet he struggles to comprehend how Aaron went from being “on top of the world” to meeting the end that he did.

An urn containing Aaron’s ashes is now part of a small shrine Real erected in the living room of his Winooski home. He plans to spread them on a mountain, per Aaron’s wishes.

Sitting at his kitchen table one day last month, Real said he has come to believe that someone had “hacked into” Aaron, likely through one of his devices, to punish him for poking around where he shouldn’t have been. Real has fed passages of Aaron’s writings into AI chatbots to mine clues from his son’s ramblings.

The grieving father recently hung on his fridge the obituary of Scott Garvey, a 55-year-old man who was fatally shot by Vermont State Police in July, three months after Aaron’s death, while experiencing a mental health crisis.

Police say Garvey had made threatening comments and scared his neighbors, leading to an hours-long standoff. It ended when troopers entered Garvey’s home, then shot and killed him because they believed he was holding a gun. He was unarmed.

Garvey’s family said he had moved to Vermont a week earlier to seek mental health services for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

“They say, ‘Well, yeah, mental problem,’” Real said. “What kind of mental problem? Was he born with it? Did it just come on to him?”

Aaron was never evaluated by a doctor, so it is impossible to know what affliction he had. Even a formal diagnosis may not have provided the clarity his father seeks.

A few weeks before his death, Aaron sent a letter to Chittenden County State’s Attorney Sarah George asking for help.

“The pain I endure is not just physical; it is a daily battle against what feels like conscious and deliberate torture,” Aaron wrote. “I feel trapped in a cycle of fear and despair, longing for relief and understanding.”

The letter, dated March 31, wound up stuffed into a mailbox at the Burlington criminal courthouse. By the time it finally reached George’s desk, Aaron LaRoche was dead.

The original print version of this article was headlined “‘I’m Not Well’ | A young man’s battle with mental illness led to a spasm of violence in Milton”

This article appears in Oct 1-7 2025.