Winooski School District superintendent Wilmer Chavarria strode purposefully through the hallways of the Onion City’s modern educational complex, walkie-talkie in hand. The building was quiet, but in less than an hour, a new school year — and all the unpredictability, energy and noise sure to accompany it — would be under way. Chavarria stopped to exchange playful banter with staff members, then headed outside to check out the new arrival procedures.

Chavarria sported a tie patterned with leaves and striped button-down with rolled-up sleeves. His slender frame and tan Nike baseball cap pulled over a thick head of jet-black hair made him appear even younger than his 36 years.

“Good morning!” he chirped to students who wore new sneakers and nervous smiles. “Welcome back!”

The cheery tableau offered little hint of the turbulence surrounding Chavarria this year. A mom with two kids in tow changed the mood.

“Wilmer,” she said, “I’m so sorry about what happened to you.”

“Thank you,” Chavarria replied, then turned back to greeting students.

The mother was referring to an incident five weeks earlier when Chavarria, an American citizen since 2018, was detained by federal agents in Texas on the way home from visiting family in his native Nicaragua. Chavarria said the agents demanded his digital devices and passwords, questioned him for nearly five hours, and denied him access to legal counsel. The encounter left him shaken and frightened. But instead of lying low, he went public, doing hours of media interviews about the ordeal with national outlets, from MSNBC to Univision.

It wasn’t the first time this year that Chavarria had chosen to speak out. During the months after President Donald Trump took office, Chavarria spearheaded passage of a sanctuary schools policy in Winooski aimed at restricting immigration agents’ access to school grounds — the first district in the state to do so. He also pushed back forcefully against Vermont Education Secretary Zoie Saunders when she directed superintendents to comply with a federal order related to diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives. In June, he was the only one of the state’s 52 superintendents to join public-school advocates at the Statehouse to oppose a sweeping education reform bill that has since been signed into law.

“There’s no underestimating how much courage it takes, especially right now, to be out in front.”

Chelsea Myers

Chavarria’s outspokenness has placed him in the vortex of some of the most contentious issues of the day and, intentionally or not, turned the calm, contemplative Winooski schools chief into a symbol of resistance amid a federal offensive focused on immigrants, public education and so-called “wokeness.”

In the process, Chavarria has become a hot ticket on the speaker circuit, with invitations from the University of Vermont, Addison County School District and Vermont Council on World Affairs to discuss his vision for leadership during a fraught time. Earlier this month, Chavarria, who is gay, served as grand marshal of the Burlington Pride Parade. And next month he’ll travel to Washington, D.C., to testify before U.S. senators about his airport detention.

After Chavarria’s experience in Texas, the Winooski school board and several Vermont education organizations released statements expressing solidarity. Some admirers saw bravery at work.

“There’s no underestimating how much courage it takes, especially right now, to be out in front,” said Chelsea Myers, executive director of the Vermont Superintendents Association.

But Chavarria hardly sounds like a fearless crusader.

“I’m actually very scared all the time,” he said in an interview. The trick, Chavarria said, is to not let that fear keep him from doing what he believes duty to his community demands.

That community — Winooski — is the only school district in Vermont with a majority non-white population. Its roughly 830 students come from all over the world — from Somalia to Iraq, Bhutan to Myanmar — and collectively speak around 25 languages. Many are resettled refugees. In the school’s atrium, enlarged photographs of smiling kids showcase that mix of cultures and national origins.

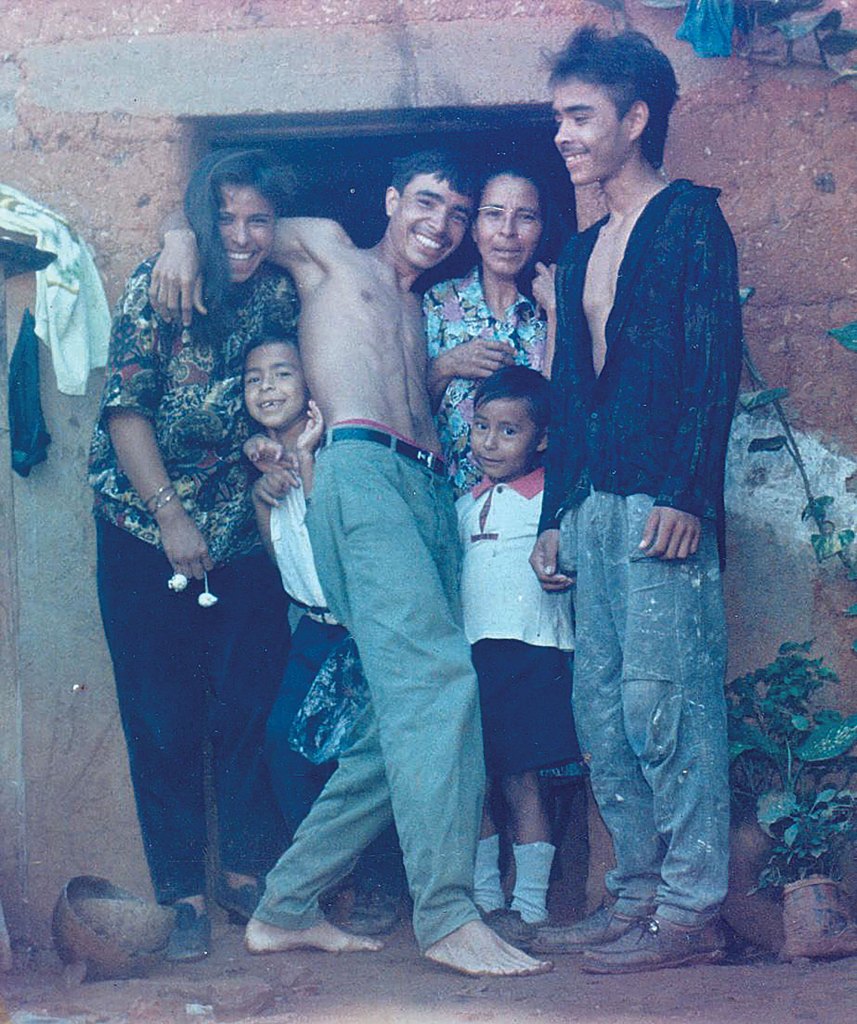

Chavarria has much in common with those he serves. Born in a refugee camp in Honduras amid political upheaval in Central America during the 1980s, Chavarria and his tight-knit family returned to neighboring Nicaragua when he was still a baby. He grew up poor, peddling bread in the street, but would find a ticket to a better life through education. His academic success eventually enabled him to study in Canada and the U.S., travel widely, build a career, and support his mother and extended family in Nicaragua. He learned English as a teenager and speaks it with some of the lilt of his native Spanish.

If Chavarria can sound personally invested in the issues he has confronted this year, it’s because he is. Even before his own run-in with immigration authorities, he had to say goodbye to his older brother, sister-in-law and two teen nieces, who had been living with Chavarria and his husband in Williston under what is known as temporary protected status. When the Trump administration announced it would end the program, the family chose to leave voluntarily in April. Champlain Valley Union High School, where the girls were enrolled, awarded them diplomas before their departure.

Vermont Gov. Phil Scott, a Republican, has advocated for a more measured response to Trump’s policies, reasoning that it is better to go about one’s business quietly to avoid conflict or possible retribution. And though it might seem prudent for Chavarria to keep his head down, too, he has no plans to shut up.

“As a superintendent, I can’t stop standing for the things I stand for. I can’t stop speaking out for the rights of our families. I’m not going to be one more manager or bureaucrat,” Chavarria said. “This is where we’re tested.”

‘That’s the Job for Wilmer’

In January 2023, Winooski launched a national search to replace superintendent Sean McMannon, who had led the district for a decade amid escalating tensions over race. After George Floyd’s murder, a group of high school students and recent graduates called on the Winooski School Board to accept a list of demands aimed at combating racism. The high school’s sole Black teacher resigned, calling out a “white supremacist culture,” and some of its student athletes spoke out about racist comments they’d endured during sports competitions.

In hunting for a new superintendent, the district sought an experienced leader adept at working with a culturally diverse student body and able to handle such potentially divisive issues.

“He modeled for folks how you build bridges versus burn them down.”

Amy Rex

The board picked Chavarria, who for two years had been working just a few towns away as the Milton Town School District’s director of equity and education support systems. One of his heaviest lifts in that politically divided community had been the creation of an equity policy, the idea of which drew strong pushback from a small but vocal group of residents who believed it marked a form of “critical race theory,” an approach usually employed in higher education that is a frequent target of the Right.

Chavarria navigated that situation and other complex issues by listening with an open mind to opposing viewpoints and countering misinformation with facts, recalled Milton superintendent Amy Rex. “He modeled for folks how you build bridges versus burn them down.” The school board voted to pass the policy.

When Rex learned that McMannon, a good friend, was planning to leave the superintendent’s post in Winooski, she thought, “That’s the job for Wilmer.”

The Winooski School Board thought so, too. Robert Millar, who heads the board and participated in the search, said he was immediately struck by Chavarria’s life story and its similarities to those of many Winooski students. Millar was also impressed by Chavarria’s wide experience as a teacher and administrator.

That included five years working as a high school English teacher, then as an elementary school principal in northern New Mexico’s Española Public Schools, where 95 percent of the student body is non-white. While working at the high school, Chavarria received a state designation as an “exemplary” teacher, based in large part on gains his students had made on standardized tests. His accomplishments caught the eye of Española’s then-superintendent, Bobbie Gutierrez, who became a mentor.

“Kids loved him. He was engaging. He was interesting. He cared about his students,” Gutierrez said.

At 29, Chavarria became principal of the biggest elementary school in Española. He delighted students by rolling down the school’s long hallways on a scooter. But his leadership was also tested when, at the beginning of his second year, a 5-year-old student went missing, prompting a massive three-day search. The girl’s body was found in the Rio Grande, and her stepfather was subsequently convicted of her murder.

Gutierrez said Chavarria showed deep empathy toward the girl’s family and the school community.

“He took care of everyone,” Gutierrez said. “I think I knew then, He’s gonna be really great someday.”

In 2020, Chavarria moved to Vermont at the height of the pandemic so that he and his husband, Cyrus Dudgeon, a high school English teacher, could be closer to Dudgeon’s parents, who now live outside of Windsor. Chavarria accepted a position as principal of Readsboro Central School in southern Vermont, thinking that running a school with fewer than 50 students would be low stress and allow him to learn about Vermont’s educational system while he pursued a master’s degree at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

But the job proved harder than he’d thought. The school district was in the throes of decoupling from a neighboring district, and it was difficult to find qualified teachers willing to work for low pay in what looked like the middle of nowhere. Chavarria wore himself down with constant work and travel, and his physical health declined. His sister, a doctor in Nicaragua, convinced him to resign for the sake of his well-being.

Although he held the post only a year, Chavarria had an outsize impact, said Readsboro School Board chair Cindy Florence, by creating a student council and basketball league and helping boost academic achievement. Florence said Chavarria’s communicative, student-centered approach won people over in Readsboro, an overwhelmingly white community with a majority of Republican voters.

Risky Business

Chavarria’s first year in Winooski produced little drama. But Trump’s second election in 2024 sent shudders through the heavily Democratic city, which boasts the largest percentage of immigrants and refugees in the state.

“Things since November have been particularly hard for a lot of folks in Winooski,” said Millar, the school board chair. “Every month seems to be a new test.”

Even before Trump took office, Chavarria was thinking about how he could protect Winooski’s immigrant students. At a January meeting of the liberal-minded school board, he introduced a sanctuary schools policy.

The policy, based on guidance from national legal groups, called for the district to limit sharing student and family information with federal immigration authorities and prevent immigration agents from entering the school without a judicial order. It also would prohibit school staff from collaborating with federal agents without authorization and require the district to provide immigrant families with information explaining their civil rights.

At the time, school board member Nicole Mace, a lawyer, expressed reservations, noting that during Trump’s first administration, jurisdictions that adopted sanctuary policies were targeted for cuts to federal funding and heightened law enforcement.

She was worried now about “shining a light on our community and bringing with it some unintended, unwelcome consequences.” She also didn’t want to give false comfort to students and families over how much protection the school district could provide, given the federal government’s broad authority to enforce immigration law.

Other board members recognized Mace’s concerns but believed Winooski should do whatever it could to protect its residents. One member, Kamal Dahal, noted that Winooski was already a target by virtue of its diverse student body.

Chavarria acknowledged that passing a sanctuary schools policy came with risks, but he favored a targeted response to protect immigrants over simply an expression of solidarity or some “performative” resolution.

Chavarria recounted a mother telling him that she was afraid to send her child to school, fearing she would be taken while he was away.

“This is not hypothetical to me at all,” he told the board. “These are our families. These are our children, and they are afraid.”

Teachers, students and community members came out in force at the board’s next meeting in support of the policy.

“A school is not just a building. It is a sanctuary. It is the last refuge, the last line, the last promise,” recent Winooski High School graduate Nixandy Ferdinand said during public comment. “We are students, and school is our right. Not a favor, not a privilege — a right.”

The board approved the policy that night, prompting thunderous applause and making Winooski the first — and, to this day, only — school district in the state to adopt such an approach. Mace, who missed the vote because of a death in her family, said she still has concerns about the risks. In neighboring Burlington, which also has a large immigrant population, the school district declined to consider a sanctuary schools policy in part over concerns about attracting unwanted attention, according to a spokesperson.

So far, immigration officials haven’t shown up on Winooski’s campus, and Chavarria concedes he can’t predict how things would unfold if they did.

Still, he said, “people feel a little safer … because we as a formalized institution have affirmed that there’s a problem, and we’ve taken the time to put a plan in place.”

Everyday Struggle

Chavarria assumed the role of advocate again in April. Education Secretary Zoie Saunders had emailed school leaders and directed them to sign a form affirming that their districts were following Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which bars any program or activity that receives federal funds from discriminating based on race. The Trump administration has said repeatedly that diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives are discriminatory on those grounds and might violate that law. Saunders encouraged districts to review the form with their own lawyers before signing and returning it to the agency.

Despite being told by the district’s lawyer that signing the attestation was harmless, Chavarria said, he bristled. The next morning, he sent Saunders an email stating that he would not sign and told his staff that he had “requested that the state grow some courage and stop complying so quickly and without hesitation to the politically driven threats of the executive.” Chavarria also sent Saunders a copy of a letter that New York’s education department had sent to the feds questioning the U.S. Department of Education’s authority to demand that a state agree to its interpretation of the law.

“I encourage our state agencies to support our districts with that level of commitment,” Chavarria wrote to Saunders.

Chavarria shared his reasons for refusing to sign the attestation with Rex, his former boss in Milton, and with several media outlets, explaining why he saw no legal justification for doing so.

“You can’t be an advocate and stand for things without getting in trouble.”

Wilmer Chavarria

Representatives from the Vermont Superintendents Association and other education groups responded by banding together to oppose Saunders’ approach. Within hours of the wider pushback, Saunders walked back the directive, telling superintendents that her agency would send federal officials a single letter certifying Vermont’s compliance with current law and rejecting conditions not supported by law.

“In no way, did the AOE direct schools to ban DEI,” she said in an email to superintendents.

In an emailed statement last week, Saunders said she is “united” with Chavarria in “our commitment to ensuring that every student in Vermont feels safe, supported, and welcomed at school.”

“In a time of increasing federal uncertainty,” Saunders’ statement continued, “the Agency of Education has prioritized being disciplined, thoughtful and factual when evaluating and responding to changes in federal policy to ensure that school leaders receive clear, consistent communication.”

Two months after the dustup with Saunders, in June, Chavarria joined a rally in front of the Statehouse as a legislative committee hashed out the final details of a sweeping education reform bill, with a special focus on how independent schools would be protected. He minced no words.

“I am just as energized as many of you are to … not be apologetic nor polite about calling bullshit when there’s bullshit happening all around us,” Chavarria told the small crowd of public-school advocates who had gathered to protest the bill, H.454. Days later, the legislation passed, setting the stage for major changes to the way education is governed and financed in Vermont. Chavarria later lambasted the process, in which some independent schools were shielded from changes they opposed, as “unethical, shady, lacking in transparency, politically manipulative and extremely exclusionary.”

Chavarria has been more vocal than his fellow school superintendents, but that could change under the intensifying pressures of wider political tumult and threats to public education.

If a school administrators is “up to the task of being [a] public, intellectual and civic leader,” there is an opportunity for them to “really clarify what the basic needs and rights are of the kids in the community,” said Elijah Hawkes, a former principal of Randolph Union High School who now trains school leaders at the Upper Valley Educators Institute in Lebanon, N.H.

But outspokenness also carries risks. Those risks depend on “the vision and values” of the local community, Hawkes said. In addition, “We’re at a time when there are powerful forces outside of the local context who are scrutinizing what’s happening.”

Chavarria understands this.

“You can’t be an advocate and stand for things without getting in trouble … You’re supposed to be quiet or simply do what the owners of the entity are telling you to do,” Chavarria said in an interview. “It’s a struggle every day.”

Chavarria’s detention at the Houston airport was a terrifying shock. As he waited in the immigration line, Chavarria was directed to go to an officer’s booth, then escorted to an interrogation room, where he was questioned about his marital and work status. Initially, he denied the officers’ request to turn over the password to his work computer because it contained private information on students that is typically protected by federal law. But eventually he relented, and the officers searched the devices out of view; he doesn’t know what, if anything, they downloaded.

The agents eventually released Chavarria, but the next day he received an email from U.S. Customs and Border Protection saying his Global Entry, a federal program allowing expedited screening at border crossings for approved, low-risk travelers, had been revoked.

Chavarria chose to speak to the press about the experience, he said, in an attempt to control his own narrative and “so people don’t get used to all this stuff being normal.”

In the wake of his media blitz, Chavarria received letters of support from all over the country, he said, but also “creepy stuff” — encrypted emails to his official account that insinuated the feds had dirt on him and messages accusing him of being a pedophile or harboring illegal immigrants. To prevent further harassment, his email address was removed from the school district’s website.

Several weeks after the incident, Chavarria received another email from Customs and Border Protection saying his Global Entry status had been reinstated, with no explanation as to why. It was a positive development, Chavarria said, but also mystifying since he hadn’t requested it. U.S. Customs and Border Protection did not respond to a request for comment.

Planting the Seeds

Chavarria’s belief in supporting those on the margins was cultivated long before he arrived in Winooski. In 1983, amid armed conflict in Nicaragua, a pregnant farmer named Petronila Gonzalez was forced to flee her home deep in the rainforest with her four children. She walked north through steep, muddy terrain, praying she and her children would survive. After three weeks, United Nations officials picked up the family and took them to a refugee camp in Honduras.

In the eight years Gonzalez lived there — first in a tent, then a small hut surrounded by plants — her husband, Santana Chavarria, who had been conscripted to fight in Nicaragua, occasionally visited. After one such visit, Gonzalez gave birth in 1989 to her seventh child, a boy she named Wilmer Alfredo.

The following year, as Nicaragua stabilized, Gonzalez and her children were repatriated to the northern city of Ocotal with little more than some plants and seeds she had taken from the camp. They were looked down on as outsiders but eventually secured a plot of arid hilltop land on the outskirts of town. Her older children, some of them teens, built an adobe house, and Gonzalez planted a small garden with sour oranges and lemongrass she’d carried from Honduras in sardine cans, alongside capulin cherries and achiote.

Young Alfredo, the name Chavarria went by as a child, was eager to go to school and tagged along to kindergarten with his sister’s son. He stood out academically but struggled to follow directions, wandered from school and erupted over seemingly minor things. Chavarria ended up at an alternative high school, one “for broken toys,” as he puts it. But the supportive environment reignited his spark for learning. He graduated from high school at age 15 and was named valedictorian of his region, an honor that carried a full scholarship to the Universidad Centroamericana in Managua, the capital.

Chavarria says he was helped by the compassion of his mother and teachers in the face of his challenging behavior. Through his career as an educator, he said, he’s tried to show the same empathy to students who are struggling.

In his first year of university, Chavarria was picked to study a rigorous interdisciplinary curriculum in British Columbia under an international network called United World Colleges that gathers students from across the globe. Chavarria was eager to go to Canada, even though he knew just a handful of rudimentary English phrases.

While living on a remote campus with 200 teenagers from 150 countries, Chavarria learned English quickly and came to appreciate the human commonalities that supersede national boundaries.

He took it all in with “the most open heart and open mind,” said Margaret Paul, Chavarria’s host mother in Canada.

Chavarria’s global view further expanded at Earlham College, a Quaker school in Indiana, where he studied cinematic arts and spent several summers with Israeli and Palestinian high school friends, working with teens from the occupied West Bank to explore the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Upon graduating from Earlham, he worked with Indigenous journalists in Bolivia, at local TV stations in Costa Rica, and with independent filmmakers in England, the Netherlands and Italy as part of a prestigious Watson Fellowship.

Chavarria said living and learning with fellow students from all over the world taught him that it’s possible for people to coexist peacefully despite fundamental differences. It also proved solid training for what he’d encounter in Winooski.

Nobody has to tell Chavarria why a prayer room is something to be taken seriously, he said, or why having an annual community iftar matters. He believes that advocating for LGBTQ students is vital but even as a gay man can understand that some of Winooski’s Muslim families fundamentally disagree with homosexuality.

“Living with that tension and knowing how to operate and support everyone through those seemingly conflicting worldviews,” Chavarria said, “that’s been built since my early years.”

Leading the Charge

On a late Sunday morning, a few weeks after school began, Chavarria stood at the corner of Burlington’s City Hall Park, natty in a glen plaid blazer and skinny tie he’d received as a gift from a well-wisher after the airport episode. He’d been asked by Pride Center of Vermont to lead hundreds of marchers to the waterfront and make a speech — a sure sign of his newfound celebrity.

It was Chavarria’s first Burlington Pride Parade, and he had brought his husband and in-laws to walk alongside. Amid a sea of colorful costumes, Chavarria’s crew stood out for its sartorial reserve. An umbrella topped with a rainbow flag was Chavarria’s only nod to the day’s theme.

Just before noon, members of the percussion group Sambatucada! began beating their drums. A Winooski parent, wearing an outfit stamped with rainbow-hued handprints, approached Chavarria to ask if she could march with him. “Of course,” he told her.

Chavarria waved to the clusters of people gathered along Main Street, bobbing his umbrella exuberantly to the music while his father-in-law took photos.

On the grassy shore of Lake Champlain, he hung back with his family under a shady tree as throngs lined up for ice cream and Indian food and browsed booths selling LGBTQ-themed merch or promoting organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union of Vermont and the Vermont Coalition for Palestinian Liberation.

When he took the microphone, Chavarria mentioned his recent detention and said he still didn’t know why he had been questioned.

“None of us is safe in this country, and we should not pretend otherwise,” he said with some emotion. “But feeling defeated is giving them what they want.”

“We cannot wait for justice,” he told the people sitting on the grass below him. “We have to take matters into our own hands.” That meant taking care of each other, he said, regardless of differences such as country of origin or sexual orientation.

“Let’s be ourselves, and let’s exist loudly,” he implored.

What battles may loom for schools in the weeks and months to come is anyone’s guess. For now, Chavarria is focused on getting the year off to a smooth start for the hundreds of Winooski students and families who depend on him and his staff.

Later this year, he plans to board a plane to Nicaragua to visit his 71-year-old mother. It’ll be his first flight since his summer ordeal, and he is unsure how it will unfold. But the Winooski School Board is taking precautions tailored for a time of uncertainty: It has authorized shipment of a work computer to the family home in Ocotal so that this time, Chavarria doesn’t have to fly with one.

The original print version of this article was headlined “Put to the Test | Winooski schools superintendent Wilmer Chavarria was detained by U.S. border officials in July. He’d been an advocate for those on the margins long before then.”

This article appears in Sept 24-30 2025.