In a few short weeks, the City of Oaks will hum with energy as residents and visitors converge on downtown Raleigh’s streets, plazas, bars, and nightclubs to catch bluegrass and Americana bands and celebrate the arrival of fall.

It’s all free, and with more than 200,000 people in attendance, you’d never know how little Wake County—North Carolina’s fastest-growing and most populous county and home to the state capital—spends on the arts.

“It’s a struggle,” says David Brower, the executive director of PineCone, the nonprofit hosting the Raleigh Wide Open music festival, of the fundraising. “It’s a struggle every single time, the big things are hard, and the little things are hard …. We go into it completely on faith that we’re gonna come out in the end.”

Along with the workaday challenges of budgeting, applying for public and foundational funding, and finding private sponsors that come along with producing the festival each year, this year, PineCone has the added challenge of having to do it all on its own after Raleigh Wide Open’s predecessor, the International Bluegrass Music Association’s World of Bluegrass Festival, departed the city for Chattanooga.

“Free is hard,” Brower says. “We go into it with some startup money from municipalities, but most of it, we’re drumming it up ourselves from corporate supporters and keeping our fingers crossed that the weather is going to be good and people are going to come out and spend money.”

PineCone isn’t alone in facing these challenges. While arts organizations in Raleigh receive robust support from the city, much of that funding is tied directly to operations and programming. Organizations with capital needs, especially those that own their facilities, face steep challenges in coming up with the money to pay their mortgages and rent, keep the lights on, and make needed repairs.

A new collaborative draft plan for arts and culture in Wake County, which was presented to the board of county commissioners on Monday, aims to address some of these challenges while supporting creative communities across Wake and strengthening “the arts and cultural environment for families, businesses, and residents,” according to the draft titled “Cultivating Creativity.”

“Cultivating Creativity charts this path forward, ensuring every resident can access meaningful cultural experiences in their own community, while positioning Wake County as a leader of artistic innovation and creative excellence,” the plan states.

But arts leaders say the need is dire—and immediate.

Raleigh’s Contemporary Arts Museum (CAM), a stalwart institution in the city’s cultural fabric, is considering selling its two-story, circa-1910 urban revival–style building in downtown’s Warehouse District, valued at $11 million. Its board chair, Charman Driver, says CAM’s leaders “are working hard to make sure CAM exists for many, many years,” but it’s hard to imagine the museum outside of its iconic space.

There’s also the storied North Carolina Theatre, which closed earlier this year after filing for bankruptcy. The nonprofit studio-gallery Artspace, near City Market, needs $5 million to replace its dated, 19-unit HVAC system, according to executive director Carly Jones. Across downtown, galleries and nonprofits alike—311 Gallery, the City Market Artist Collective, the Visual Art Exchange—have had to close or relocate because the rent is just too damn high and the funds aren’t there to support them.

“I think people take the arts for granted,” says Jones. She says while residents love public art and music festivals and family-friendly cultural activities, there’s a disconnect in the general public’s understanding of how much it takes to make these events happen, and how intentional arts supporters—governments, private and corporate funders, foundations—must be in ensuring artists can live and work in Raleigh.

The vast majority of the city’s cultural events, and certainly the free ones, are hosted by arts nonprofits—but even with the financial support they receive, it’s difficult to break even.

“If we want a thriving arts and culture sector, we have to put into [it], because artists are working individuals,” Jones says. “I love us, I love our city, but I also know we’re not proactive, we’re reactive, and my concern is it’s gonna get really empty down here. And then all of a sudden people are gonna be like, ‘Oh, Raleigh’s boring, there’s nothing to do there,’ because [artists are] who’s providing the things to do.”

A cultural master plan

Across Wake County, public support for the arts is strong. So is the cultural ecosystem that currently exists.

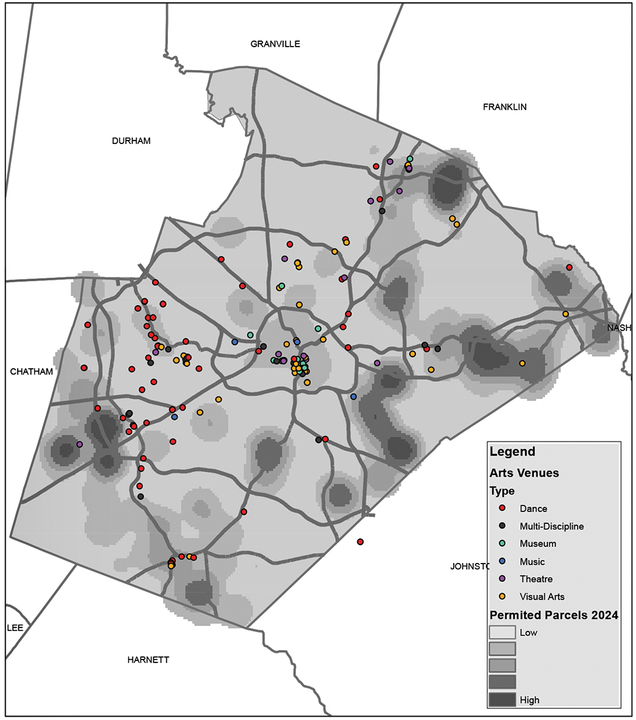

According to data from the Cultivating Creativity final draft plan, there are currently more than 300 nonprofit arts organizations in Wake. Together, they generate $103.7 million in revenues annually and $1.5 billion in creative industry earnings and support more than 51,000 creative jobs.

And while 71 percent of Wake residents participate in cultural activities frequently or occasionally, according to a survey of more than 1,700 residents, and “strong” personal support for government funding of the arts ranges from 71 percent (in Raleigh) to 51 percent (in Fuquay-Varina), at 41¢ per capita arts funding, Wake County is well below its peers.

“If we want a thriving arts and culture sector, we have to put into [it], because artists are working individuals.”

Carly Jones, executive director of artspace

Mecklenburg County, for instance, spends $7.73 per person on the arts. Orange County spends $4.65 per person. Fulton County, Georgia, Fairfax County, Virginia, and Montgomery County, Maryland, all peer counties to Wake in terms of population and growth patterns, spend $5.60, $4.38, and $6.61 per capita, respectively, on the arts.

Part of the reason for Wake’s low spending is that Wake County has 12 municipalities that United Arts Wake County, the county’s designated local arts agency (LAA), has to support on an annual budget of less than $2 million. Part of it is that the state legislature’s 2023 increase of $2.5 million to its $6.3 million NC Arts Council Grassroots Arts Program did not extend to counties with populations of more than 250,000.

“I understand the [state’s] philosophy behind trying to get funding to rural areas,” says Jenn McEwen, president and CEO of United Arts, who oversaw the development of the cultural master plan. “But [Wake has] small communities and rural areas, and so there’s a disproportionate kind of injury effect to our county.”

The result, McEwen explains, is that while United Arts can provide funds without spending parameters, those funds are more thinly spread, and organizations don’t always receive the full amounts they request.

Indeed, within Wake, the disparities between the county’s municipalities in regard to arts spending are stark. Raleigh allocates more than $27 million to arts and culture in its budget, including money that goes to public arts facilities and venues. Cary spends $6.2 million. Apex, the county’s third-largest town, budgets $343,760 for the arts, while on the lowest end, Wendell and Morrisville spend $32,500 and $30,000, respectively.

The Cultivating Creativity plan takes a three-pronged approach to addressing some of these disparities by enhancing municipal infrastructure and capacity for the arts, supporting and enhancing a sustainable arts sector and creative economy countywide, and building access to and awareness of the arts and local culture.

Goals include establishing a collaborative arts and culture program for all 12 municipalities, helping municipalities expand their public arts programs, expanding the Wake Murals project, developing new initiatives for nonprofits for operations and programming, launching a program to expand the county’s creative economy, establishing an artist-in-residence program, and enhancing the county’s cultural brand image and marketing initiatives.

The plan envisions several ways to fund its goals.

One idea is to establish a $1 million biennial Cultural Assistance Technical Program from the county’s interlocal hospitality taxes that would allow smaller towns (populations below 200,000) and organizations (budgets below $3 million) to apply for funding to support capital improvement projects and repairs.

Another is to expand and diversify public and private funding through partnerships with corporations, foundations, and United Arts, in order to increase resources and build sustainability. Finally, there’s a proposal to expand annual general fund allocations to United Arts, which would be up to the county commissioners, in order to move “toward peer county levels over time.”

more from the indy fall arts issue

A tricky time for the arts

So where does this all leave the City of Oaks, home to downtown Raleigh, arguably Wake County’s premier arts and cultural destination?

While funding from the city is nationally competitive—Raleigh dedicates 1 percent of municipal construction funds for public art, and the Raleigh Arts Commission supports the arts at an annual rate of $5 per person—those funds typically can’t be used for arts infrastructure or other capital projects. And it’s a different landscape for artists and their advocates these days.

“It’s just a really tricky time for all the typical sort of arts organizations to do things like buy a building, revitalize a neighborhood, get low-interest loans to be able to build it out,” says Sarah Powers, the executive director of Raleigh Arts, who has worked in the arts on both the nonprofit and policy side of arts fundraising. “Things are a lot different right now. So those struggles are compounding.”

Wake County, like Mecklenburg, is too large to receive more grassroots funding from the state, and, arts leaders say, Raleigh and Wake lack the corporate community buy-in that Charlotte has leveraged.

“I’ve been raising money for a long time for different organizations,” says Driver, CAM’s board chair, “[and while] the North Carolina Museum of Art does get big dollars, you just don’t see it [in Raleigh] like you see it in other cities. It’s an issue, and it’s one that we should probably look closer at.”

Philanthropic groups and individuals could also provide an avenue for capital support, but, local arts leaders say, there’s also a role for the county commissioners to increase funding to the arts.

The county’s interlocal fund—which has supported Marbles Kids Museum renovations, Red Hat Amphitheater’s relocation, the NC Museum of Art’s expansion, the expansion of the Raleigh convention center, and renovations at the Lenovo Center in the past—could be one way to support arts organizations and their capital needs.

“There is an opportunity for the county to step up,” says Michele Weathers, the producing artistic director of Raleigh Little Theatre. While there’s the recommendation in the Cultivating Creativity plan to use a limited amount of the interlocal fund for small towns’ and organizations’ capital needs, Weathers, Artspace’s Jones, and other arts leaders say it’s something county leaders could further explore.

Wake County and the City of Raleigh are currently accepting applications for more than $23.5 million in hospitality tax revenues available for qualifying projetcs, but the opportunity to apply is only offered once every two years, and only projects worth more than $100,000 that have already secured other funding are eligible. Smaller arts organizations are welcome to apply, but traditionally, parks, museums, stadiums and other athletics facilities have been awarded funds.

“There could be a bit more transparency, I think, for me personally, on how [the interlocal fund] could be an avenue as it relates to the per capita [spending], for us in Raleigh, particularly,” Weathers says.

“We see arts as critical to downtown’s future. It’s been a big part of its overall rebirth. If you think about the last 20 years, some of the early sort of organizations and people who came into downtown to populate the storefronts, were artists.”

Bill King, CEO of the downtown

raleigh association

Downtown Raleigh sees more than 20 million visitors annually, according to the most recent report from the Downtown Raleigh Alliance (DRA), and contributes more than $62 million to the city and county in property, hotel, and food and drink tax revenue. With more than 180 public art installations and 18 performing arts and concert venues, not to mention free and ticketed arts and music festivals, First Friday events, and various museums and galleries, it’s fair to say arts and culture are major drivers of downtown foot traffic.

“We see arts as critical to downtown’s future,” says Bill King, the CEO of the DRA. “It’s been a big part of its overall rebirth. If you think about the last 20 years, some of the early sort of organizations and people who came into downtown to populate the storefronts, were artists.”

The DRA’s five-year economic development strategy, which it embarked on this year, centers public art and growing an arts and entertainment district in Raleigh as a way to activate downtown. The Illuminate Art Walk this past winter is one example, and the DRA has worked to provide studio, gallery, and pop-up spaces for artists as tenants.

“You’ve got to have the ecosystem for artists to actually be here and be supported and be able to make a living off of that, so you have them to feature and highlight,” King says. “So that’s a big part of [the plan].”

Still, with corporate support lagging behind places like Charlotte, and limitations on what funds from local governments and many philanthropic foundations can be used for, arts leaders say they’re increasingly looking to individuals who support the arts to help sustain local artists and their organizations. There’s something we can all do, it turns out, to support the arts, whether it’s going to shows and exhibitions, giving money when we can, talking to our elected leaders, or sharing our experiences on social media.

Weathers, of Raleigh Little Theatre, says they are working to “maximize our relationships with individuals, because that’s where we have the greatest influence.”

“People come to our shows, they take our classes, they volunteer here,” she says. “The arts do have an advantage, in that way, the performing arts, in particular, in that we get to see our patrons quite frequently.”

PineCone’s Brower echoes this. He says he wishes more residents would go out and “experience the arts and music,” attend the different cultural events—and then tell people about their experiences.

“Tell either their elected officials … or friends, just tell their community that they did that,” he says. “First and foremost, just come on out and see what’s happening out here, and really make it integrated into your life. And I think when people start integrating [art] into their lives, they’re going to say, ‘Hell yeah. This should be supported.’” W

Send an email to Raleigh editor Jane Porter: [email protected]. Comment on this story at [email protected].