Every visitor to Shelburne Farms remembers their first glimpse of the Farm Barn. Around an initial bend of the long driveway onto the 1,400-acre property, the massive turreted copper roof and clock tower rise into view like a fairy-tale castle.

That universal “wow” moment contrasts with the breadth of reasons people come to the former Gilded Age estate on the shores of Lake Champlain. On any given day, youngsters twirl sheep’s wool into bracelets or learn to milk a patient Brown Swiss cow. Teachers in hands-on workshops crisscross the farm, exploring ways to bring environmental lessons to life for their students. Walkers, runners or snowshoers ply 10 miles of trails. Families pile out of tractor-pulled wagons to visit piglets and watch cheesemakers at work. Guests at the elegant mansion-turned-inn wander the formal gardens and graze on farm-grown lamb with roasted zucchini and fennel in the marble-floored dining room.

One hundred and thirty-nine years ago, William Seward Webb and railroad heiress Lila Vanderbilt Webb created a gated refuge for a single family. Today, Shelburne Farms is open to all, a treasure to the Vermont community around it and a resource for educators across the globe. An estate originally dependent on private wealth has become a robust nonprofit with almost $16 million in annual income, including revenue from the farm’s cheddar, inn stays and contributions from donors worldwide.

The pandemic interrupted Shelburne Farms’ most ambitious capital campaign yet, which aimed to raise $50 million. It ultimately concluded last December with a marathon runner’s sprint to the finish line, surpassing its goal by $12 million and setting up the nonprofit for its next phase. The infusion will help reach more teachers, build an endowment, and restore and upgrade the 19th-century buildings that are both an incredible asset and a costly burden.

Already, the 123-year-old Coach Barn has undergone a multimillion-dollar overhaul; it will reopen this fall as an energy-efficient learning center and hub for professional educator programs called the Institute for Sustainable Schools. The project epitomizes how Shelburne Farms has used its historic legacy to serve the future — and how far the nonprofit has come from its idealistic bootstrap start.

The journey has been as winding as the property’s dirt roads, through spectacular scenery but with some rough patches.

“Shelburne Farms is the model of how to take old and private wealth and turn it into commonwealth.”

Bill McKibben

By the 1960s, the Vanderbilt wealth was long spent and the grand buildings were crumbling when a new generation of Webbs made a radical choice. Instead of cashing in their inheritance, Lila and Seward’s great-grandchildren set themselves the daunting task of turning the faded estate into a nonprofit. It teetered on the brink of financial failure for the first decade and beyond. Compromises had to be made, including selling and leasing some acreage.

But gradually, Shelburne Farms and its young visionaries found their footing and the nonprofit has flourished. The United Nations has honored its leadership in sustainability education. The restored buildings and sweeping grounds have earned a National Historic Landmark designation and a spot alongside the Great Pyramids in the travel bible 1,000 Places to See Before You Die. More than 160,000 visitors passed through the gates in 2024 — free of charge, since the nonprofit never reinstated entrance fees that were suspended during the pandemic.

“Shelburne Farms is the model of how to take old and private wealth and turn it into commonwealth,” said Bill McKibben, an environmental activist and writer who lives in Ripton.

In 2022, the same year the nonprofit celebrated half a century, one of those great-grandchildren, Marshall Webb, died unexpectedly at age 74. Along with his younger brother Alec, he had devoted his life to the idea that education in such an unforgettable place could inspire visitors from around the world to care for their own natural environments and communities.

Marshall’s death left his brother the sole member of the nonprofit’s founding generation on the farm. As Alec, the organization’s longtime president, approaches retirement age, there’s no Webb heir apparent — a reminder that the estate is no longer a family property, nor is it run by a family foundation. His successor is likely to have a different last name.

The story of Shelburne Farms so far interweaves a place, a family and a mission. In its next chapter, the tale may take a different turn.

A Fine Farm

Marshall Webb declared he would leave Shelburne Farms forever if his father followed through on a plan to sell 500 acres to a developer. His younger brother Alec, though less prone to vocal protestation, knew he would do the same.

It was 1969, and the Webb family fortune had been in decline almost since the estate was created.

When Lila Vanderbilt Webb’s railroad tycoon father died in 1885 and left her $10 million — the equivalent of $333 million today — the bequest called for a grand statement. To build their refuge from New York City life, the Webbs amassed 4,000 acres in Shelburne and commissioned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted to plan the sweeping grounds. Dozens of buildings designed by Robert H. Robertson included not only Shelburne House, set above expansive gardens, but equally resplendent barns for Seward’s model farm.

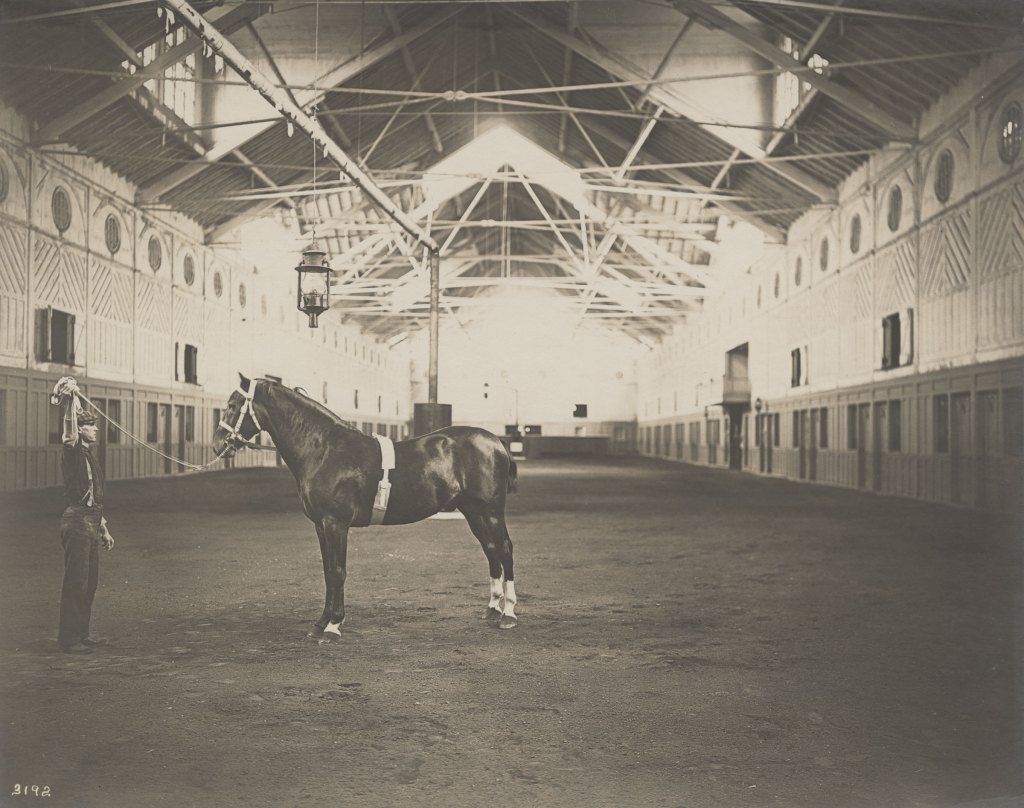

Practicing a common form of noblesse oblige for the time, Seward aimed to develop prime breeding stock and demonstrate modern practices. The Queen Anne-style Farm Barn housed up to 80 work mules and stored 1,500 tons of crops. The monumental Breeding Barn provided Seward’s champion stallions with a year-round, electrically illuminated exercise ring longer than a football field. Even the shingled piggery was palatial.

“It is doubtful if there is any finer farm in the United States,” the New York Record asserted in 1893.

Meanwhile, family and visitors — including president Theodore Roosevelt in 1902 — whiled away the days sailing on the lake, playing golf on one of the earliest private courses in the country, and dining on freshly hunted pheasant and melons grown on-site in glasshouses.

But the lavish lifestyle and Seward’s ambitious farming schemes gobbled money. Cracks began to show by the mid-1890s, after a Wall Street panic decimated a stock company Seward co-owned and his railroad projects suffered losses. To rein in spending as World War I loomed, the farm manager was instructed to defer building upkeep.

By the 1950s, when Seward and Lila’s grandson Derick Webb inherited a whittled-down, 1,800-acre estate, the farm was no longer quite so fine.

Derick applied himself to turning a gentleman’s farm into a real farm. He developed a purebred Brown Swiss dairy herd, for which he built a free-stall pole barn in the middle of the estate’s overgrown golf course.

“Our souls at an early age became entwined with the spirit of the farm.”

Marshall Webb

Unlike the earlier Webbs, Derick and his first wife, Elizabeth, lived year-round on the farm and raised their six children there. Derick supported the family comfortably but not extravagantly with money he had inherited, and he strove to break even on the farm. Beyond the milking operation, he invested little in the property. Roofs leaked, walls crumbled, and manure piled up in the barn courtyards.

“It was all about the dairy. He let everything else go,” Alec said of his father.

The Webb children grew up in an old farmhouse near the dairy. Like countless farm kids, they fed calves, hayed and shoveled out barns. Their childhood memories smell of silage, the haymow and the comforting constancy of manure wafting from Derick’s overalls hanging in the garage.

From Quentyn, the eldest, down the line to Marshall, Mary, Alec, Lisa and Robert, they grew up absorbing their father’s bond to the land and their mother’s love of nature. As Marshall later said, “Our souls at an early age became entwined with the spirt of the farm.”

The family boiled sap in the Coach Barn and played basketball in the dense steam, using sound to guide passes. Alec remembers lambs being castrated there every spring. “I was glad I wasn’t a sheep,” he said dryly.

As soon as the weather warmed, the Webbs moved into Shelburne House, or what they called the Big House. Alec, now 73, described it as “an overgrown summer camp.” Half the heating system had been pulled for scrap metal during World War II, only some plumbing worked, and Lisa remembers scurrying around to set out buckets when it rained.

Robert’s pet crow flew all over the house, and the family’s yellow labs slept on the original velvet sofas. Lisa kept ducks in the lily pond in the formal gardens and a goat in the ramshackle servants’ quarters. Alec wishes he could find a treasured snapshot of his family eating from paper plates on wooden picnic tables on the terrace, corn in hand, with “a goat standing there looking over at us.”

Their father was not one to broach difficult topics, Alec said, but Derick could not ignore his mounting debt. Things came to a head in 1969, when Derick started a series of family meetings in which he eventually told the kids, ages 11 to 23, that he saw no way around selling at least 500 acres. The cash, he hoped, would provide a cushion to preserve the heart of the farm and buy some time to hammer out a longer-term plan.

Marshall and Alec weren’t alone in their vehement reaction. Lisa, now 70, remembered the siblings pleading with their father: “Is there another way?”

‘A Bunch of Crazy Hippies’

Inspired to do more than save a place they loved, the young Webbs began brainstorming ways to turn the private estate into a public good — “something to make a positive difference, to help address environmental and social problems outside of Shelburne Farms,” Alec said. “It was a means to an end, as opposed to an end in its own right.”

Their unanimous decision seems remarkable, but Alec said it felt like the only choice. Beyond the farm, the world was rocked by the Vietnam War and Woodstock, the civil rights and women’s liberation movements. Young people were devouring Silent Spring, Rachel Carson’s book about the harmful effects of pesticides, and Helen and Scott Nearing’s Living the Good Life: How to Live Sanely and Simply in a Troubled World. Twenty million Americans would take to the streets on the first Earth Day in 1970.

The kids started working to convince Derick they were serious about using the farm as a living environmental education classroom. Alec ran summer camps for a mix of kids from Burlington, the Bronx and Black Tickle in easternmost Canada. Marshall and his first wife, Emily Wadhams, later took over the camps with Lisa’s help and started the Market Garden where it remains today.

Inspired to do more than save a place they loved, the young Webbs began brainstorming ways to turn the private estate into a public good.

“We ground our own wheat and made our own bread and yogurt. We made pancakes with cattail fuzz,” Emily recounted. Campers slept in a grab bag of tents near the garden, where they helped grow vegetables to eat and sell. They cooked over a campfire and used garden hoses for running water.

It was no surprise that Derick’s first cousin Watson Jr. dismissed his young relatives as “a bunch of crazy hippies,” Emily recalled with a laugh.

In 1972, Derick, Elizabeth, Alec, Marshall and Emily signed legal documents to establish a nonprofit with the lofty goal of educating “the public to recognize the wealth in natural, rural resources and to use that wealth for the satisfaction of individual and common human needs.” The four older Webb kids and Mary’s husband put in $10,000 of seed money.

Alec was just 20 and Marshall and Emily only a few years older. Quentyn had returned from Vietnam — scarred mentally and physically, according to his family — but he was working on the farm and became the nonprofit’s first president.

Alec, an introvert and pragmatist, recalled thinking, “If it’s a financial problem, then I’ll figure out the finances.” He apprenticed with the farm accountant and became his father’s bookkeeper. Father and son successfully presented a case for tax stabilization to the town. It didn’t solve the money problem, but it helped.

Margy Holden was on the Shelburne School Board in the early ’70s when Alec asked to come over to chat about the nonprofit’s plans. The earnest, soft-spoken young man reminded her of the Roosevelt adage “Speak softly and carry a big stick,” Holden recalled. “But his stick was not aggression; it was passion. You couldn’t turn your back on it.”

In summer 1971, a Shelburne neighbor and Nature Conservancy volunteer, Marilyn Leimenstoll, led teacher environmental education workshops at Shelburne Farms. She began working closely with Alec to build support for the nonprofit and raised the first $20,000 to repair the Farm Barn’s manure-rotted timber frame.

Even as the decrepit buildings felt like an albatross to the fragile organization, Marilyn always believed they would draw people in and provide a way “to instill some of our environmental goals,” she recalled.

Alec and Marilyn’s shared passion for the nonprofit grew into something personal. They married in 1975 and built a small house on Shelburne Farms with a composting toilet, no upstairs heat and a windmill for power.

‘On the Edge’

The nonprofit’s first dozen years were touch and go. No family member received a salary for close to a decade. Some prospective donors balked at giving money to people they perceived as wealthy, even though the Webbs’ assets were largely tied up in the land they were desperately trying to turn into a public service.

Marilyn recalled a few pitches that came to a grinding halt as listeners protested: “We can’t give money to the Webbs.”

The family soldiered on, patching up the buildings and gradually adding school field trips and community events, including the first Vermont Mozart Festival concert on Shelburne Farms — a harpsichord duet in the crimson silk-walled dining room in 1974. Two years later, Derick signed over the Farm Barn, Coach Barn and Shelburne House to the nonprofit. It was a vote of confidence but came with no money or land, a major fundraising roadblock.

At one point, Marshall traded a prized electric guitar to pay a painter. “We’ve been on the edge since 1970,” he said in a 1979 interview.

Marshall took responsibility for the grounds and buildings while Alec focused on behind-the-scenes management and still regularly milked cows. Marilyn, the third leg of the leadership stool, became the nonprofit’s president and spokesperson.

The urgent need for cash persisted. In the late ’70s, the Webbs invited O Bread Bakery and Beeken Parsons woodworking to use space in the Farm Barn. The collaborations generated some revenue for the nonprofit and also fostered a productive hive of land-based enterprises.

Encouraged by entrepreneur and environmentalist Paul Hawken, the Webbs built their own businesses, too. In a 1981 letter, Hawken urged Alec to explore value-added foods, and later, as a board member, he pushed for turning Shelburne House into an inn. Such enterprises would not only bring in money but could be a way to spread their message, he wrote.

Similar to the era’s popular Whole Earth Catalog, which paired tool reviews and ecological evangelism, Hawken explained, “By selling a good garden fork, I am given permission, so to speak, by my customers to talk about soil conservation and other values.”

Derick did eventually sell 500 acres outside the main gates to pay down debt he had accumulated keeping the property afloat. By that point, his offspring understood it was a necessary compromise, but Alec penned increasingly urgent letters to his father arguing the case for giving the remaining land to the nonprofit. Reading these today, Alec recognizes his own temerity. He now realizes that Derick was weighing his kids’ idealism against his responsibility to manage the family’s biggest asset.

On March 13, 1984, Alec picked up the phone to learn that Derick had died of a heart attack at age 70. After absorbing the loss, his mind flew to the unsettled will and a possible forced sale to pay inheritance taxes.

Unbeknownst to his offspring, Derick had left the property to the nonprofit. It felt like a miracle.

But then, Alec said, “the work really began.”

Building a stable financial base to fund their big dreams for the property has been a Herculean task since the first capital campaign launched in 1984. It raised almost $2.5 million to turn an old gatehouse cottage into a visitor center, improve safety and accessibility of the Farm Barn and Coach Barn, and restore the main house.

Following heated board debates about whether the nonprofit should be in the hotel business, Marilyn managed an intense renovation of Shelburne House into a seasonal inn and restaurant. It opened in 1987. Shortly after, Marilyn and Alec divorced. Always uneasy in the spotlight, Alec stepped warily into the public eye as the nonprofit’s new president.

For almost 40 years since, Alec has remained more comfortable working in the background even as he has steadily steered Shelburne Farms forward in partnership with the board, his older brother and longtime staff. Key among those has been Megan Camp, who has led the education programs at Shelburne Farms since 1985 and later became its executive vice president. She and Alec were married in 2005.

The nonprofit’s operating budget has leaped 100-fold from the early 1980s, and it now employs almost 100 people year-round, a number that doubles every summer.

When he died in 2000, Derick’s cousin Watson Jr. left the nonprofit $2.5 million. The bequest was a welcome surprise: Watson had apparently changed his mind about his hippie younger cousins.

Over the decades, Shelburne Farms has continued its dual mission of investment in its historic grounds and buildings and in education initiatives. In 1993, the renovated Farm Barn opened with the McClure Center for School Programs in one wing, providing a year-round base for youth education, from weekly preschool programs to summer camps. More recently, the purchase of a private home and 66 acres on Windmill Hill provided more housing for educator workshop participants and reintegrated land in the property’s heart that had been sold for much-needed cash years earlier.

The reach of Shelburne Farms’ education work has traveled far beyond the place where it was born. Project Seasons, the farm’s 1986 book of science-based lesson ideas and activities for elementary school teachers, has been translated into eight languages, from Ukrainian to Japanese, and printed or downloaded almost 20,000 times. Partnerships have helped Shelburne Farms send educators from Vermont to as far as Eastern Europe and China. All of this, plus the nonprofit’s leadership in the farm-to-school movement and collaboration with the University of Vermont on Education for Sustainability certificate programs, has spread ripples of learning as wide as a perfectly skipped pebble.

The Power of Place

On a July morning more than half a century after Shelburne Farms became an education nonprofit, 21 teachers circled up to watch UVM ecologist Walter Poleman make rocks fizz. The mission and the place that inspired it were on full display on a lakeside beach between the inn and the Coach Barn.

The educators came from as far as Missouri and represented a range of classroom ages and subjects. Poleman gave a quick geological recap of the land on which they stood and noted, “If not for the chemistry of the rock, Shelburne Farms would not be an agricultural place.”

He asked for help applying a few drops of diluted hydrogen chloride to rocks the participants had gathered from the beach. Those that fizzed contained limestone, a clue as to why the soil on Shelburne Farms makes good forest and farmland.

Guided by the farm’s education team, the teachers were spending a week traveling around the farm, from the inn gardens to the dairy, learning hands-on how lessons on wild pollinators, forest ecologies and farm-to-food cycles could engage their students.

At the end of the session, Poleman pulled out a guitar crafted from butternut and sugar maple, with a carved Brown Swiss cow bone inset into the neck and a strap made from cowhide. The instrument had been made by a professional with materials from the farm, but Poleman said he has worked with students to make similarly sourced canoes and skateboards. Simpler projects for any age, he said, can “weave the science of place together with the art of making things.”

Shelburne Farms serves about 8,000 youngsters annually through field trips, day programs and camps, but its main focus is on professional development for more than 1,500 teachers a year in person and online. They become missionaries of the sustainability gospel, sharing what they’ve learned with students and colleagues.

“A one-day field trip isn’t going to really change somebody’s attitudes and values, skills and behavior,” noted Megan, 64. Even before 1982, when she first came to Shelburne Farms as a UVM intern pursuing a self-designed environmental education major, she was asking, “What does it look like beyond the field trip?”

Megan’s thesis research revealed that many teachers were intimidated by the national mandate in the early ’80s to integrate science into their classrooms. Her data led to Project Seasons, a groundbreaking book that helped teachers and kids understand that “science is really about the food you eat. It’s the earthworms in the ground. It’s the rain and the weather,” she explained.

Raised by educators, Megan grew up believing in the power of education to make change. Her initial focus, like that of the early Shelburne Farms nonprofit, was on environmental education, but the scope has expanded with what is now called sustainability education.

During a spring workshop, for example, educators visited the farm sugar bush and did an observation activity with the Children’s Farmyard sheep and goats. But they also traced everyday items, such as toilet paper and a lunch box, from materials to manufacturing and eventual disposal, considering the environmental, economic and human impacts of each step.

The approach “is about improving the quality of life for all,” Megan said. “It’s all about connections and relationships.”

Sustainability education goes beyond studying the natural world to investigating how people rely on it and interact with it — and brings it home with how such knowledge can help them steward their corner of the Earth. “You’re building a sense of place,” Megan said. “You’re looking at the relationship between people, land and agriculture in that place.”

The emphasis on place-based learning is critical, explained Liz Soper, a senior director with the National Wildlife Federation who has partnered with Shelburne Farms for 20 years. “Your place is what you can put your hands on, what you can see,” Soper said. If kids love the natural resources and the community around them, she said, they will want to protect them.

“Shelburne Farms helped me identify my purpose as a teacher. I’m empowering my students to make the world a better place.”

Olapeju Okungbowa

Partly because it is such a remarkable place itself, Shelburne Farms brings this lesson to life; one only has to hear the story of the Webb siblings to understand its power. But unlike Seward and his state-of-the-art farm, Megan and the education team never frame Shelburne Farms as a model. Rather, they focus on how everyone learns from each other. Their humble, collaborative approach makes them successful, Soper said.

Olapeju Okungbowa was teaching fourth grade in her native Nigeria when she found the Shelburne Farms website in 2017. She had never heard of Vermont, and teacher training on a farm “didn’t quite make sense,” she said from Morocco, where she now teaches middle school and facilitates educator trainings.

But she did enroll in a workshop and has returned five times, bringing colleagues and leading some sessions herself.

With Shelburne Farms’ support, Okungbowa started a student club in Nigeria in which members canvassed their neighborhoods to identify and grow healthy, sustainable practices. Youngsters picked up trash, did energy audits and started a school garden. The project earned a National Geographic Society grant to expand with students in Africa, India and the U.S.

“Shelburne Farms helped me identify my purpose as a teacher,” Okungbowa said. “I’m empowering my students to make the world a better place.”

As Shelburne Farms’ reputation has grown, demand for workshops has exceeded its capacity. This month, after more than a year of painstaking, historically sensitive renovation, painters and carpenters put the finishing touches on the Coach Barn before it reopens as the hub for the Institute for Sustainable Schools, a net-zero, year-round home for educator programs. It will also host cultural and community events but far fewer private gatherings than in the past — and no weddings.

Beyond teaching sustainability, Shelburne Farms is committed to walking the talk. The $10 million Coach Barn overhaul includes all-new mechanical and electrical systems, including geothermal heating and cooling pumps. It takes a major step toward the nonprofit’s goal to be carbon-neutral by 2028, a deadline set by Marshall before he died to coincide with his 80th birthday.

In the cobbled stalls where horses once rested, teachers will now cluster for breakout sessions. In the central hall where carriages and sleighs rose on a lift to the second floor, flip charts will bloom with ways to inspire and empower youngsters to care for the Earth.

‘End of an Era’

There’s always more to do: more money to raise, more roofs to fix, more teachers to reach. The historic buildings and grounds soak up about $1.5 million a year just for routine maintenance. The farm’s 30-year-old milking parlor needs a $1 million upgrade. Welcome Center renovations had to be kicked down the road to allow for the repurchase of Windmill Hill.

The decision not to reintroduce entrance fees after suspending them during the pandemic has cost the nonprofit at least $350,000 a year, but Alec said he has no regrets: “Just seeing people walking here all the time is so beautiful.”

Such trade-offs are constant but mostly hidden from the thousands of visitors dazzled by the farm’s natural and built beauty.

Shelburne hit 95 degrees on August 10, but the cavernous Breeding Barn remained relatively cool. That was much appreciated by 30 cheesemakers and 1,000 attendees of the 13th annual Vermont Cheesemakers Festival as they glanced up admiringly at the soaring rafters, where swallows loop-de-looped as if outdoors. Until the pandemic, the festival was held every summer in the Coach Barn. This year, it returned to Shelburne Farms, but to Southern Acres, part of the property that is not on the standard public circuit.

In 1994, Shelburne Farms made the weighty decision to reabsorb a portion of Southern Acres, part of the estate that Lila and Seward gave their eldest son, Watson Sr., 80 years earlier. That branch of the family later donated much of the acreage to Shelburne Museum, founded by Watson’s wife, Electra, with her own sugar empire fortune.

The Breeding Barn was the gem and the money pit of Southern Acres’ historic buildings. Restoration was beyond the mission of Shelburne Museum, and the land was at risk of development. With some philanthropic support, Shelburne Farms agreed to take on the “daunting challenge of managing and sustaining more land and another immense facility,” as the nonprofit’s board chair, Chuck Ross, put it at the time.

Appropriate to its massive scale, which includes two acres of copper roofing, the Breeding Barn has required massive investment to stabilize and repair. A multiyear Getty Foundation grant, National Park Service funding and several million dollars more in private pledges have helped it safely welcome the public for occasional large events.

In fall 2022, 1,000 people filled the Breeding Barn for a celebration of life for Marshall, who had died in August of a heart attack while swimming in the lake with two young grandchildren. He was buried in a plain pine box crafted from wood he had harvested on the farm.

The death left a gaping hole in the family and at Shelburne Farms. While Marshall had technically stepped back after mentoring several replacements for his multifaceted job, “No way was he ever really going to retire,” said Kate, his wife of 33 years. Marshall’s connection to Shelburne Farms was “complete,” she continued. He and Alec “shared a sense that it was bigger than themselves.”

Marshall’s eldest daughter, Molly, has taken on a larger role advising the net-zero effort, which her dad drove with characteristic big energy and big ideas. The 51-year-old tech and climate change expert lives in London but returns to Vermont several times a year. She believes that her father’s 2028 deadline is achievable, “though it’s not going to be easy.” The future beyond that is harder to see.

Part of the shock of losing her dad, Molly said, “was that it seemed like the end of an era.”

For decades, the two brothers played valuable, complementary roles, according to 15-year Shelburne Farms board member Andrew Meyer: “Alec was responsible for the day-to-day operations, where Marshall could dream a little bit more and cultivate these incredible ideas.” Meyer recalled many times watching Marshall smile while his younger brother smiled back, trying to “figure out how he would implement one of Marshall’s ideas.”

“He liked pushing me out of my comfort zone,” Alec said with appreciation. Marshall pushed with particular urgency around how Shelburne Farms could reduce its own climate impact. “I was always like, ‘There’s only so much we can do,’” Alec said. “He was always, ‘Can we do more than we’re doing?’”

The nonprofit is actively working on a succession plan for the role of president. Alec politely deflected the question of whether Shelburne Farms loses something without a Webb at the wheel. It will be the board’s job to pick the best person, he said. “Ideally, it will be somebody for whom it’s more than a job,” he conceded. “It’s a life. It’s a passion.”

Few people know that better than Heidi, the younger of Alec and Marilyn’s two daughters. She worked in higher ed fundraising for a decade before joining Shelburne Farms’ development team in 2016.

Heidi, 43, lives with her family in her childhood home on the farm. The upstairs now has heat, and the composting toilet in which she once threw a shoe as a toddler is long gone.

It took Heidi years to consider working for the nonprofit that consumed her parents’ lives when she was young. She recalled her discomfort when one tour guide would spot her playing and stop the wagon to announce, “This is the great-great-granddaughter.”

Heidi demurred when asked if she’d ever step into her dad’s shoes. She said she has different strengths and believes she serves the nonprofit best where she is. Shelburne Farms started with one family but has thrived because of the dedication of many, Heidi said: “Good things don’t come just because of one or two people.”

Meyer, the nonprofit’s outgoing board chair, acknowledges that Shelburne Farms will certainly feel different without a Webb at its head.

“The siblings started this with their blood and sweat, their belief and life commitment to this organization,” Meyer said. “It’s them, but it’s also much bigger than them at this point.”

The original print version of this article was headlined “A New Heyday | How the family behind Shelburne Farms bootstrapped a crumbling Gilded Age estate into a beacon of sustainability education”

This article appears in Sept 17-23, 2025.

![Leaping Lambs at Shelburne Farms [SIV346]](https://www.communityspiritevent.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/1758123404_516_Shelburne-Farms-New-Heyday-in-Sustainability-Education.webp.jpeg)