In the summer of 1951, a gallon of gas cost around 19¢, a gallon of milk 83¢, and the United States was celebrating its demisemiscentennial. In Chapel Hill, 71-year-old Rachel Crook was approaching the end of her PhD in economics at North Carolina’s flagship university.

By that September, she would be dead.

That summer was colder than normal, per historical accounts, though that doesn’t mean all that much for a North Carolina August. In the evenings, Crook liked to take out a chair to the porch to relax with her cat and watch passersby—a well-earned rest for a septuagenarian who worked by day as a fishmonger at the 610 West Franklin Street shop she’d opened on the border of Chapel Hill’s Northside neighborhood.

A former chicken house that she’d renovated into a shop where she also lived, Crook’s Corner had an “unusual but misleading name,” a 1949 article in the Chapel Hill Weekly quipped, forebodingly.

It was on the shop porch that Rachel Crook was last seen, the night of August 29, 1951, before her body was discovered the next day in rural Orange County. The scene was bad: Her face was battered beyond recognition and she appeared to have been raped. Flesh under her fingernails suggested a struggle.

The questions around Crook’s death, still an open cold case, are the subject of a gripping new podcast series, Who Killed Rachel Crook?, produced by Hillsborough publisher and editor Elizabeth Woodman. The four-part series is a special edition of Woodman’s podcast, 27 Views, which she has been producing since 2002.

“Everybody knew that something terrible had happened to this woman,” says Woodman, “but the details of her life, the fact that she owned Crook’s … the fact that she was a graduate student—that all kind of got lost in the noise.”

“Everybody knew that something terrible had happened to this woman, but the details of her life, the fact that she owned Crook’s … the fact that she was a graduate student—that all kind of got lost in the noise.”

Woodman has operated a small press, Eno Publishers, since 2009. When she lost her distributor in 2019, she decided to start recording material for her podcast series with the North Carolina writers—Randall Kenan, John Jeremiah Sullivan, Jill McCorkle, and many others—she’d worked with over the years.

“I thought, you know, I’ve been a print editor,” Woodman says. “I’m going to learn this. I bet I can do it.”

One of the writers Woodman had worked with was the novelist Daphne Athas, whose memoir, Chapel Hill in Plain Sight, Woodman published in 2010. In 2022, several years into producing 27 Views, Woodman’s friend Bill Massengale Sr., an Orange County attorney, suggested that she revisit Athas’s book, which contained an account of Crook’s murder.

“You have to do something,” Woodman remembers Massengale saying, “about Daphne’s story about Rachel Crook.”

In a way, it’s surprising that the true crime genre hasn’t reached the Crook case before now. The eventual trial, once the Orange County sheriff’s department charged a suspect with murder, has all the hallmarks of a case ripe for reexamination: an overeager sheriff; a silver-tongued defense team; a compromised jury; a rushed deliberation.

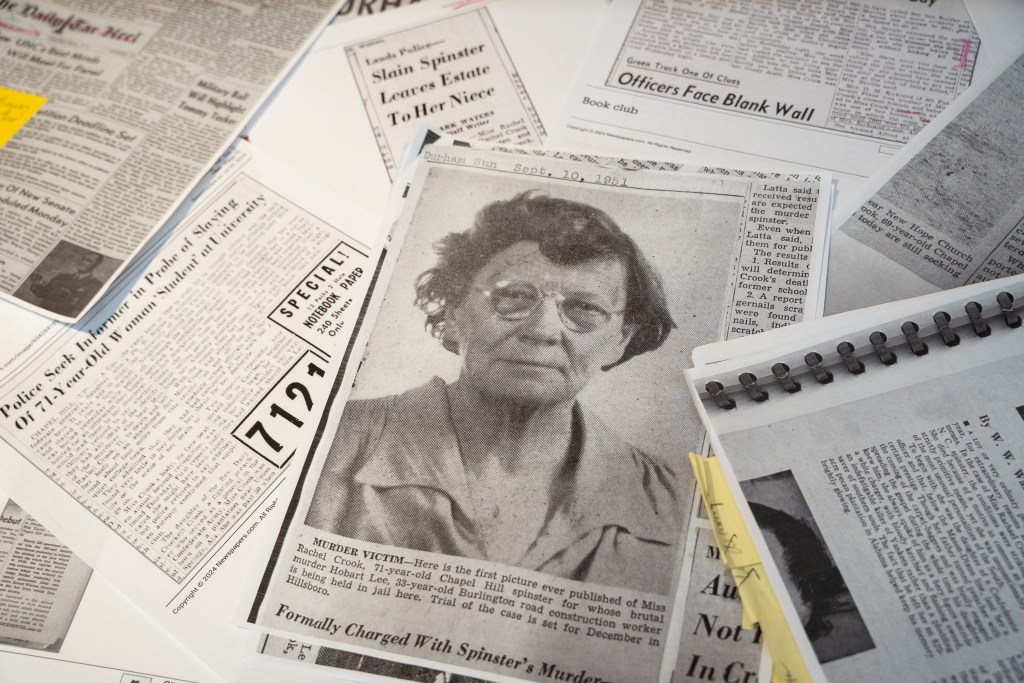

And then there’s the victim. Rachel Crook makes for an almost absurdly compelling protagonist. In photos, she bears a slight resemblance to the writer Shirley Jackson: horn-rimmed glasses, a heavyset frame, a keen, knowing expression.

The daughter of an aged Confederate brigadier general, Crook was orphaned and raised by grandparents who invested in her education. After securing bachelor’s and master’s degrees, she moved to Chapel Hill in the early 1930s to pursue a late-in-life dissertation, financing her degree by working odd jobs.

She gardened, wrote for local papers, and sold fish and pecans. She babysat local children, including the children of famed playwright Paul Green. She opened the first coin-operated laundromat in Chapel Hill. Waggishly scrappy, she lived for several years in a child’s playhouse—dimensions seven feet by seven feet—paying $1.50 rent to the eight-year-old child to whom the playhouse belonged. She never married.

“I don’t mind being a character,” Crook told a Chapel Hill Weekly reporter in a profile the newspaper wrote on her, two years before her murder.

According to Woodman, Crook had a wide social circle that seemed to have accepted her, quirks and all. The night of August 29, she had an appointment with a seamstress friend.

“I think that Chapel Hill was a safe place for her,” Woodman says. “A place where, as an unmarried, entrepreneurial woman—kind of an enigma, even in Chapel Hill—they could accept her.”

When Crook failed to show up for the appointment, her friend ventured over to West Franklin Street to look for her. Crook’s Corner was empty, save for the cat. The chair the fishmonger normally brought out to the porch was still sitting outside.

In 1982, three decades after Crook’s murder, the building got new tenants: Gene Hamer and Bill Neal. It had churned through several life cycles—taxi stand, bait and tackle shop, pool hall—before Hamer and Neal took it over, carrying the name on from its prior occupant, a pigs-and-ribs joint owned by a town council member who’d kept the name in Crook’s honor.

Hamer and Neal put Crook’s Corner on the map. The pair had chosen a “down-at-the-heels establishment with a rather unsavory reputation in a section then called ‘No Man’s Land,’” as a 1985 New York Times review of the restaurant ascertained, for their seasonal Southern joint.

It suited them just fine: Soon, Hamer and Neal (and later chef Bill Smith) transformed Southern household ingredients—honeysuckle, condensed milk, fish muddle—into legendary dishes: shrimp and grits, boned quail, honeysuckle sorbet, Atlantic Beach pie. Crook’s was the “Tigris and Euphrates of Southern food,” as the novelist Daniel Wallace wrote in a remembrance when the restaurant shut down, after nearly 30 years.

Wallace isn’t the only one with strong feelings about Crook’s: Over the years, it’s taken on a transcendent, near-mythical dimension, drawing in townies and professors, UNC-Chapel Hill students and parents on families’ weekend. Neal was a prolific reader, weaving quotes by Eudora Welty and Carson McCullers into his cookbooks, lending Crook’s a literary quality that was only heightened by the Southern Gothic veneer of Rachel Crook’s life and death.

For some people, the spot stayed haunted. Woodman says that Athas, who had known Crook when she was alive, categorically refused to go to the restaurant.

“Our friend [the writer] Randall Kenan loved oysters,” Woodman remembers. “I used to go to Crook’s and eat oysters, and [Daphne] wouldn’t go. She just could not bring herself to go to Crook’s Corner.”

Athas, who died in 2020 at 96, shared certain biographical elements with Crook: unmarried, unconventional, a Chapel Hill academic who “seemed to live her life exactly as she chose,” as a Lit Hub remembrance of the novelist put it.

Athas’s view of Rachel Crook in her memoir, in a chapter entitled “Chapel Hill Murders,” is not particularly gracious (a whole paragraph is devoted to describing Crook’s varicose veins), but it is probably the most detailed account of what happened. Over the years, primary sources died and coverage dropped off—a cold case lost to time.

Or it would’ve been, had it not been for an overstuffed file, passed from county judge to county judge, that Woodman’s friend Bill Massengale Sr. pointed her toward. The file became the architecture of the podcast.

“I know where there’s an archive,” Woodman recalls Massengale telling her. “Lonnie Coleman, the retired judge in Hillsborough, has a big folder, a big thing of clippings and lawyers’ notes that were given to him by Bonner Sawyer.”

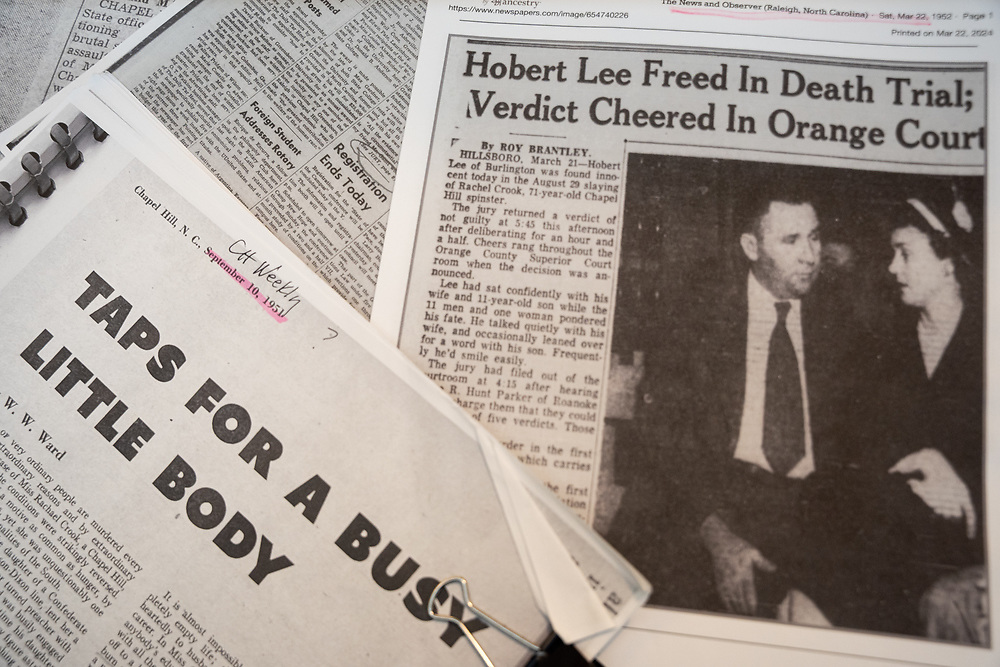

Sawyer was the defendant’s attorney in the murder trial back in 1951, back when there was a case against a suspect that seemed like a slam dunk. The suspect’s name was Hobart Lee. He had no previous known connection to Rachel Crook.

Hobart Lee, 33, a doughy-faced local construction worker, was initially brought in for questioning when his truck matched the description of one that two boys, frog gigging the night of the murder, reported having seen tearing down N.C. 86, a woman screaming inside. Lee was charged, though the case rested largely on circumstantial evidence: matching tire marks and heel prints, scratches on his face, a night he admitted he was “blackout drunk” and couldn’t recall, and a disproven alibi.

I won’t spoil the particulars of the case, which unfolds expertly across the podcast’s four episodes, with local literati reading parts in Woodman’s excellent script. You can listen and decide for yourself whether or not the case against Lee—who was, his mother assured reporters, harmless, save his proclivity to “mess” with chickens—is fair, but either way, the podcast sketches out a compelling portrait of a botched trial.

From the get-go, it was a circus. Local newspapers wrote the trial up fervently, reporting that 200–300 people crammed into the small Hillsborough courthouse to watch proceedings.

“[Lee] was facing the death penalty and was reported to have been in ‘chipper spirits,’” Woodman told me. “Spectators [were] packing picnic lunches and mugging for the camera.”

All potential Chapel Hill jurors were dismissed—locals that likely would have been more used to a woman like Rachel Crook—leaving a rural jury of 11 men and one woman (who happened to be married to one of the other jurors, anyway) to evaluate the likeliness of whether Lee, a good old boy who had previously dodged two previous sexual assault accusations, might have drunkenly preyed upon an old woman continuously identified in the media as a “spinster.”

About that Shirley Jackson allusion: In some ways, Crook also bears a resemblance to Jackson’s fictional female characters. Often, they are outsiders; often, they live brutal lives in a world built for men. Jackson’s women often face off with a menacing town chorus or their own inner demons. In this way, Crook differs: she seemed to have persuaded Chapel Hill to accept her, remaining cogent and confident to the end. She didn’t mind being a character—these were her own words—and had made it to her seventies on her own terms, before her life was senselessly taken. Was it Lee? The jury didn’t think so.

The case also seemed to have stuck with Bonner Sawyer, the prosecutor, who eventually passed down his files to Lonnie Coleman, a younger lawyer who shared his office.

“He was winding down his business,” Coleman says, explaining how he came to receive the archives, upon Sawyer’s death in 1972. “I have all his files.”

I’d left a message at Coleman’s Hillsborough law firm, though I didn’t entirely expect a call back—Coleman is now 88 and retired. Less than half an hour later, though, he rings me: “I thought maybe you were some poor soul that hadn’t heard that I was almost deaf and wanted some legal advice.”

More interesting than the file, Coleman tells me, was a conversation he had decades ago with Bill Murdoch, the prosecuting attorney. Murdoch said Hobart Lee had asked him to come into the jail after his arrest, seemingly on the verge of a confession.

“Hobart Lee is very broken and very nervous, and his chin was quivering. And Mr. Murdoch said to him, ‘Did you want to make a statement to me about this?’” Coleman recounts. When Lee replied yes, “Bill Murdoch said, ‘Well, Hobart, I’m the prosecutor. I will be prosecuting you. So I’m going to send the sheriff in here.’”

Alas, Coleman continues, the sheriff—“old-fashioned” and famously friendly, as police dealing with men of Lee’s demographic tend to be—calmed Lee down enough that something shifted: “Hobart leaves the moment of weakness. The moment of wanting to bare his soul passes.”

These days, if you drive past Crook’s, you’d be forgiven for thinking the restaurant is still open. Its automatic lights still switch on at night. The famed fiberglass pig still stands guard, casting a small, loin-shaped shadow over Franklin Street. And if you peer through the bamboo mass into the patio, you’ll spot diner-style chairs flipped over onto tables, as if a shift has just ended.

The restaurant announced its closure in June 2021. Shannon Healy, the owner of Durham restaurant Alley 26 and then part of the Crook’s Corner ownership group, told me at the time that he was “very heartbroken” and that COVID-19 had exacerbated the restaurant’s financial difficulties. An outpouring followed. Over the years, rumors have intermittently circulated about a possible second act.

Getting to the bottom of those rumors proved harder than I’d bargained for: 610 West Franklin Street, it turns out, never belonged to Gene Hamer or Bill Neal. Crook’s niece, Rachel McLain, had inherited the property after her aunt’s murder and insisted on keeping it in the family. When she died in 2017, at age 98, the building was purchased by Kinston businessman Cameron McRae with Healy and Gary Crunkleton, the owner of the eponymous Triangle whiskey bars, as the creative team.

Healy told the INDY that he is no longer involved in the restaurant’s ownership. Neither is Crunkleton. Efforts to get in touch with McRae—who, among other ventures, owns a minor league baseball team, the Down East Bird Dawgs, as well as 50 Bojangles locations across the Southeast—largely fell flat. A call to the business manager listed on the building’s ownership LLC was met with a brusque “Take me off your list.” After leaving several messages with McRae’s office, a spare statement finally arrived in my inbox: “We are having discussions with all parties involved on our future plans.”

But while I wasn’t able to determine the exact status of the historic building, I did reach others in its orbit. In late June, I met up with former Crook’s chef Bill Smith, who retired from the restaurant in 2019, right around the time it changed hands.

He arrived at Orange County Social Club late and flustered because of “a cash machine thing,” he explained—withdrawing money to pitch in for one of his former kitchen staff, whose mother is sick in Guatemala. Does he still keep in touch with employees, all these years later? “They’re my best friends,” he says.

Of the Rachel Crook murder, his knowledge is cursory: “It was in the verbal history of the place,” he says. “As Crook’s became more famous as a food destination, it lent to the aura.”

He doesn’t think Rachel Crook haunted the place, exactly—“that sounds like she was about to spring out of the bathroom”—but, if there was a ghost, “there was more than one.”

Bill Neal died in 1991 at age 41, a victim of AIDS. Randall Kenan, Woodman’s friend and maybe one of the restaurant’s more devout fans, died at age 57 in 2020. Who Killed Rachel Crook? is dedicated to Bill Massengale Sr., Woodman’s friend. He died in 2022, just weeks after suggesting the podcast topic.

As Smith and I chat, bartender Billy Buckley—by my count, the fifth Bill in this story—allows that he, too, worked at Crook’s for half of the ’90s and some of the 2010s.

“It’s hard for me to think about Crook’s without being sad,” he says, handing Smith a PBR. “It was such a big part of my life—I met my wife there—and it could still be open.”

Another patron, on his way out the door, stops to shake Smith’s hand: It’s Matt Neal, Bill Neal’s son, who opened and ran Neal’s Deli for many years, carrying on his father’s culinary legacy in another corner of Carrboro. On cue, another patron sitting at the bar leans over to tell Smith that, at a birthday party the night before, someone served Smith’s famed Atlantic Beach pie.

I’d wanted to dig into the podcast in part out of lingering curiosity about Crook’s Corner. Like its namesake, it has a history that feels unresolved and a bit haunted. Maybe those two things are the same, though. Creaks and cold spots and lights that go on and off—that’s the one kind of haunting.

But the ways that things repeat themselves, carrying on in rumors and stories, loans and cast irons, feels like another kind of haunting, something mutual and sacred—not entirely happy and not entirely sad, either. I also have to believe any kind of documentary practice—a legal file, a book on Chapel Hill history, a podcast—is partially done in debt to the dead.

“It was kind of an amazing thing to start reading through the clippings and realize that there was so much to her,” says Woodman, reflecting on Rachel Crook. “I grew to feel very protective of her, you know. I wanted to reach back in history and correct things.”

Follow Culture Editor Sarah Edwards on Bluesky or email [email protected].