Three senators and three representatives had been sitting across a table in a Statehouse conference room for two days. Their job: to reach a compromise on the House and Senate versions of H.454, the landmark education reform bill that had dominated the 2025 legislative session.

As the hours ticked by, the two sides appeared to draw closer. Checking off one section of the bill they had agreed on, Rep. Emilie Kornheiser (D-Brattleboro) quipped, “I feel like we should celebrate.”

But then on May 30, the third day of negotiations, the party ended abruptly.

Two conferees, Sens. Seth Bongartz (D-Bennington) and Scott Beck (R-Caledonia), suddenly introduced several new policy proposals that deviated dramatically from both the House and Senate versions of the bill. House conferee Peter Conlon (D-Cornwall) argued that the amendments would shield private schools — commonly referred to as independent schools in Vermont — from the substantial changes that public schools would face if the bill became law.

Education leaders and lobbyists whispered to each other as they watched the proceedings. Conlon and Kornheiser appeared rattled.

“An unvetted, unmapped-out proposal at the eleventh hour is not something I think anybody can be terribly comfortable with,” Conlon told his Senate counterparts.

The conference committee broke at 8:17 p.m. for what was supposed to be a brief recess. The two sides didn’t meet again for 12 days.

The breakdown in negotiations was the latest twist in the session’s marquee effort to reshape Vermont’s education system — a process that broke from Statehouse norms long before the bill was formally introduced and continued through months of protracted debate to the bill’s ultimate, bipartisan passage.

Education reform was forecast to be fraught and politically charged, given the differing visions held by the Democrat-led legislature and Republican Gov. Phil Scott. November’s election results had ended Democrats’ veto-proof supermajority and sent a batch of first-term lawmakers to the Statehouse, adding to the challenge of building consensus on the must-pass legislation.

Over the course of the session, lawmakers, lobbyists and the administration would disagree over how much money should be allocated for each student under a new funding formula; whether there should be class, school and district minimum sizes; who should help draw the new school district lines; and when all the changes should take effect.

But the biggest stumbling block to agreement, nowhere more apparent than at the conference committee negotiating table, stemmed from the long-standing debate over how Vermont’s independent schools should be integrated within the state’s public education system. Independent school proponents, including Bongartz and Beck, clashed with legislators and public-school advocates through the final days of the session.

Seven Days followed the reform effort from start to finish, tracking the lawmakers who cast aside legislative conventions and ignited flash points over independent schools — maneuvers that at times threatened to derail the entire overhaul.

Independent schools educate just 3,500 of Vermont’s more than 83,000 publicly funded students. Yet they have long been a bone of contention in what is Vermont’s version of the fiery national debate over whether state dollars should fund private institutions. Various attempts by the legislature and State Board of Education to make independent schools’ operations more transparent and change their enrollment practices have been met with fierce opposition by independent-school advocates and some legislators. Disagreements often fall more along geographic than party lines, since the schools have the biggest presence in Bennington County and the Northeast Kingdom.

Under Vermont’s “tuitioning” system, towns without an elementary, middle or high school can use tax dollars to send their students to their preferred public or state-approved independent schools. Some of that tuition money goes to small institutions such as Long Trail School in Dorset, ski academies such as Burke Mountain Academy, religious schools such as Rice Memorial High School in South Burlington or Grace Christian School in Bennington, out-of-state boarding schools, and therapeutic schools for students with special needs.

But the vast majority of those who attend independent schools on the public dime go to one of Vermont’s four historic academies: Burr & Burton in Manchester, St. Johnsbury Academy, Lyndon Institute and Thetford Academy. The schools, beloved institutions in their communities, were founded in the 1800s through private endowments but historically have enrolled mostly publicly funded, rural students and are integral to the educational landscape.

Unlike public schools, independent schools can raise money privately; the academies are known for their top-notch facilities and robust course offerings. But much of their operations remains opaque; their board meetings and budgets are not public, for example.

Supporters of the education bill in the Statehouse have applauded what they call unprecedented levels of coordination between the chambers and the bipartisan support the bill ultimately garnered. But the different tacks taken by the House and Senate and their leaders still left legislators scrambling to reconcile stark differences over independent schools, weeks into overtime.

By the time the bill passed, what might have otherwise been a moment of collective celebration was marred by a divided Democratic caucus, infighting among legislators, independent school proponents lamenting new constraints on their institutions and public-school advocates mourning a loss of trust in the legislative process.

Musical Chairs

The education bill’s fractious journey was set in motion before the session even began, when Statehouse leaders selected chairs for the committees that would shape its course.

State leaders knew education would be one of the main issues of the session. Voters had rejected a historic number of school budgets in 2024 to protest skyrocketing property taxes. In November, they had shrunk Democrats’ House and Senate majorities.

House Speaker Jill Krowinski (D-Burlington) reappointed Conlon and Kornheiser to chair the House Education and Ways and Means committees, respectively. The selections were unsurprising, given their incumbencies as chairs and their track records of working closely with the public-school advocates favored by many Democrats.

In contrast, Senate leaders reshaped their education committee. The Committee on Committees, the panel tasked with appointing committee chairs — Senate President Pro Tempore Phil Baruth (D-Chittenden-Central), Sen. Ginny Lyons (D-Chittenden-Southeast) and Republican Lt. Gov. John Rodgers — expanded the Senate Education Committee from five to six members and appointed equal numbers of Republicans and Democrats to encourage bipartisan lawmaking. The group selected Bongartz to serve as the committee’s leader.

Bongartz, who served in the House and Senate during the 1980s and returned to the Senate in 2020, had no experience on the Senate Education Committee. But he did have an intimate understanding of Vermont’s independent schools, having spent 15 years as the board chair of Burr & Burton Academy, his alma mater. Bongartz said his objective in this new role was to focus on outcomes for all students, not just those attending independent schools.

“It’s as simple as trying to get excellent educational opportunities for every Vermont child,” Bongartz said.

Lyons, who is serving her first term on the Committee on Committees, said the panel sought chairs with experience bringing people together and listening to different perspectives.

But some legislators and public-school advocates wondered why Sen. Martine Larocque Gulick (D-Chittenden-Central) wasn’t chosen for the role. A member of the Burlington School Board since 2018, Gulick had experience working in the public education system as a former teacher and librarian and had been vice chair of the committee during the previous session under senator Brian Campion, who retired in 2024.

Gulick even expressed her desire to lead the committee during a September 2024 conversation with Baruth, she said in an interview after the session wrapped in June. She said Baruth told her he’d been unhappy with her performance the previous session.

Sen. Ruth Hardy (D-Addison), a former fiscal analyst for the Wisconsin state legislature, had asked Baruth and then the members of the Committee on Committees to be chair of the Senate Finance Committee, or — once Gulick gave her blessing — Senate Education, if she could not have her first choice, according to Hardy and records reviewed by Seven Days. Baruth declined to comment, but ultimately the panel did not give Hardy either job.

Hardy said she was not surprised when Bongartz was named chair of Senate Education, but she was concerned given his strong ties to the independent school community and what she perceived as a limited knowledge of how public schools operate.

On Monday, Geo Honigford, a board member of the advocacy group Friends of Vermont Public Education, made formal ethics complaints against senators Bongartz and Beck over their close ties to independent schools. (Beck teaches social studies at St. Johnsbury Academy.)

Beck said on Tuesday that the complaint was baseless and a “political jab.” Statehouse counsel have generally interpreted ethics rules to mean there is no conflict unless a senator has an “immediate or direct interest” — and even then, attorneys have advised that a legislator need not recuse themselves on issues that affect both the lawmaker and a larger group of people.

Prior to Honigford’s filing, Bongartz rejected any assertion that his judgment was compromised by his long-standing ties to independent schools.

“Anything about a conflict of interest is ludicrous,” Bongartz said.

“To say that somebody who volunteers their time to serve on the board of a nonprofit organization has a conflict of interest is an unprecedented charge and is ridiculous on its face,” he added in a written statement sent to Seven Days. Bongartz also noted that several public school teachers who serve on the House Education Committee are members of the Vermont-National Education Association, which actively lobbies for public school employees.

There’s a significant difference between a lawmaker pushing for a policy that personally benefits them and one that serves their constituents’ interests, said Matthew Dickinson, professor of political science at Middlebury College. But that distinction can get lost during heated policy debates.

“That type of political sniping is pretty par for the course,” Dickinson said.

All three Committee on Committees members noted that they made compromises with one another when selecting chairs.

“Anytime you have more than one person who wants a chair, if you choose a chair, you run the risk that someone is not happy,” Baruth said.

Mapping it Out

Chairs have the power to shape the work of their committees by deciding which bills they will focus on, who will testify and how much airtime they get. Long before H.454 landed in the Senate Education Committee in April, independent schools had a notable presence in its conference room.

“One of the things we’re going to have to figure out … is how the independent schools fit into this overall framework,” Bongartz told his committee before a January 29 presentation by Oliver Olsen, a former state representative and a lobbyist for the Vermont Independent Schools Association. “Though they serve a comparatively small number of children as it relates to the whole, they play a critical role in the system.”

The Senate committee heard testimony from the heads of Burr & Burton and Long Trail School — two of the independent schools in Bongartz’s region — as well as two smaller independent schools and two therapeutic independent schools.

In contrast, the House Education Committee heard no such testimony from independent school leaders, nor did they invite them in.

The workings of a legislative committee often reflect the distinct philosophy of the person leading it, Dickinson said.

“Chairs are traffic cops, but they also are agenda setters,” Dickinson said. “[Bongartz] took advantage of his role as chair, as a good legislator would.”

On March 18, as the House was hammering out the fine points of H.454 — including the formation of a committee that would create proposals for new, merged school district boundaries — Bongartz presented his committee with his own school district restructuring map, which he told Seven Days he designed with the help of Beck.

Bongartz’s map called for the state to be divided up into six school districts and three umbrella supervisory unions. The supervisory unions would include a mix of school districts, some of which operated public schools and some of which paid for students to attend independent ones.

Bongartz said he initially believed it made sense to draw up a map before working on any other education reform efforts. He also wanted to present an alternative to the governor’s education transformation reform plan, which split the state into just five districts, he said. But public-school advocates also believed that Bongartz’s map was carefully designed to preserve school choice in his and Beck’s regions.

“We are not interested in gerrymandering to preserve vouchers,” Darren Allen, a spokesperson for Vermont-NEA, told Vermont Public.

Preaching to the Choir

A week and a half after Bongartz unveiled his proposal, he stood at a podium in the center of the packed gymnasium of Burr & Burton for an event billed as “an important discussion on preserving our local education options.” As he led the crowd through a slideshow projected on a large screen behind him, the senator appeared at ease at the institution where he once studied and later served on the board.

Bongartz kicked off his remarks by touching on the major issues facing Vermont’s education system — declining enrollment, small schools with limited educational opportunities and a “byzantine funding formula.” But he devoted the majority of his public-speaking time to the existential threat to independent schools.

“Some of them are quite literally saving kids,” he told the audience. He said he bristled when people referred to Vermont’s independent schools as “private.”

“When our opponents use the term ‘private school’ they are trying to conjure up that your daughters are going to Choate or Andover,” Bongartz said. “The independent schools in Vermont are focused on Vermont kids.”

Bongartz motioned to a slide behind him displaying quotes critical of school choice from the Vermont Superintendents Association, Vermont School Boards Association and Vermont-NEA.

“We’re under constant attack year after year,” he said, “because we’re different.”

Bongartz also directed his scorn at the House version of H.454. The “really horrible bill,” he said, limited school choice and imposed class-size minimums that would interfere with schools’ operations.

“The House is not with us,” Bongartz said.

As an alternative, Bongartz shared the map he had created, which he called “the Senate proposal.” It would consolidate school districts across the state, he told the Burr & Burton crowd, “even as it maintains our ability to have the system that we have always had here.”

The audience hung on Bongartz’s every word. After he spoke, he opened the floor for questions and comments. People spoke enthusiastically about the critical role independent schools played in their region, the high-quality education they provided and their desire to preserve them.

Bongartz acknowledged their passion. But, he told them, it was hard to get legislators from other regions to truly understand how independent schools operate, to convince them of “how deeply they care about kids and how much they … especially focus on the kids who need them the most.”

Witnesses on Parade

H.454 moved from the House to the Senate Education Committee in mid-April. The bill’s reforms largely echoed policies favored by the public-school advocates who had repeatedly testified before Conlon’s and Kornheiser’s committees.

Bongartz had abandoned his map after he determined the redistricting process would require more time than was available this session, but he appeared focused on bringing more voices of independent-school advocates to the fore as the Senate Education Committee prepared its witnesses. By that point, people affiliated with independent schools had testified on six separate occasions. Private-school officials had not appeared in any of the 14 joint hearings held by the House and Senate Education committees as of that April and had remained mostly absent from the earlier House committee hearings.

In the two and a half weeks that the Senate Education Committee spent digging into the House bill, public-school advocates were among the first outside witnesses to testify, followed later by a group of more than 20 students from public and independent schools. Later came more testimony from the Vermont Independent Schools Association, as well as from St. Johnsbury Academy and Beck.

“I really try to get everybody in, from every perspective, and hear them,” Bongartz said.

The committee tackled issues of both education governance and financing as it worked and also updated the House version in several key ways that added greater flexibility to independent schools. While the governor’s proposal and the House bill prohibited state dollars from flowing to out-of-state schools, the Senate version allowed independent schools and public schools within 25 miles of the state border — such as Northfield Mount Hermon in Massachusetts — to accept public tuition from Vermont. The Senate committee also decided that the task force that would draw new school district boundaries would be composed solely of legislators and would not include the group of public-school experts called for by the House.

“The bill that came out of the [Senate] Education Committee was, in my view, very carefully crafted, down to the sentences and words and making sure we had things right,” Bongartz said.

But it was clear that the bill had doubters, not just on the issue of independent schools but also for the ways it would change school financing and local decision making.

“It’s a weird position to be in, to feel very hesitant and actually quite concerned about a lot of the things in this bill,” committee member Sen. Nader Hashim (D-Windham) said before the unanimous committee vote. Though Hashim voted yes, he said he hoped more changes would be made as the bill moved through Senate Finance, the full Senate and ultimately the conference committee.

A Hardy Intervention

By mid-May, the Democratic-led Senate Education and Finance committees had both advanced H.454 with little enthusiasm. Only Hardy and Gulick voted against the bill in the Finance Committee, but the senators who voted yes expressed reservations about its specifics.

So widespread and serious were these concerns that at a May 20 party caucus, Baruth told Senate Democrats that the bill did not have enough support from their party and he worried bringing it to the floor would undermine its credibility as a bipartisan proposal. He needed to get more members of his caucus on board if the reform effort was ultimately going to succeed.

He decided to use an unusual procedural move to suspend Senate rules, strip the Senate changes from H.454, return to the House-passed version of the bill, then design an amendment to the House iteration before bringing it back to the Senate floor for a vote.

That gave Sen. Hardy an opening to weigh in on the legislation. Though she was upset about the ways in which the Senate Education and Finance committees had changed the House version of the bill, she agreed to help craft an amendment to it after four senators — not including Baruth — had asked her to help.

What followed, Hardy said, was an intense day and a half of working with legislative staff to draft a comprehensive amendment that retained much of the House language but made key changes, including slightly lowering the percentage of tuition students required to enable an independent school to receive public dollars, an attempt to reach a compromise between the House and Senate provisions.

Still, the amended bill was not acceptable to Bongartz. Hardy said she understood Bongartz’s issues were primarily with the parts of the bill that weren’t friendly to independent schools. Bongartz, meanwhile, said later that he took issue more broadly with the “prescriptive” approach of Hardy’s amendment regarding issues such as class size and education spending.

On May 22, Hardy and Bongartz decamped to a room to negotiate. Their talks continued into the next day.

The bill was reshaped largely around Hardy’s amendment, Bongartz said, with a few of the Senate Education Committee’s ideas reintegrated into the proposal.

As Hardy sat with Bongartz, she said, she tried to press him on what informed his values, particularly around independent schools.

Though “he was not as receptive as I would have liked him to have been,” Hardy said, he did tell her, just as he had told the crowd at Burr & Burton months earlier, that he believed independent schools “save kids’ lives.” Hardy said she told Bongartz that she believed public schools did, too.

Ultimately the two senators signed off on a revised version of Hardy’s amendment that they agreed to bring to the full Senate. It stopped money from going to out-of-state independent schools. But it allowed approved independent schools to continue accepting public dollars if at least 25 percent of their Vermont students were already tuitioned in that manner, a percentage that Bongartz thought indicated that the school was essential to the educational landscape.

Several hours after Hardy and Bongartz presented the new wording to the Democratic caucus, the Senate passed H.454 by voice vote. On the floor that day, Baruth singled out Hardy, thanking her for doing “yeoman’s work” on the bill.

Butting Heads

The six members who make up a legislative conference committee are tasked with reconciling the House and Senate versions of a bill. Each chamber sends three conferees. The Senate’s choice of Bongartz and Beck — in addition to Senate Finance Chair Ann Cummings (D-Washington) — raised eyebrows in the public-education community and even among some legislators.

“I think the obvious bias to private schools was really stark,” Sen. Gulick said in an interview.

Baruth defended his picks. Bongartz and Cummings were “no-brainers” because of their respective positions as education and finance chairs, he said, and Beck made sense because of his familiarity with the issues involved and his position as the Republican minority leader.

In the case of H.454, the House and Senate bills weren’t vastly different because the Senate had adopted much of the House language. It wasn’t hard, then, to imagine a scenario in which the conference committee came to an agreement in relatively short order.

But on day three of deliberations, Beck and Bongartz introduced the new provisions related to independent schools that were in neither the House nor Senate versions of the bill. One measure would have allowed public-school districts to spend less than the state-allocated foundation amount if they got voter approval, while requiring districts that paid for their students to attend independent schools to pony up the full amount. Another would have allowed independent high schools to set their own tuition, while public schools were locked into spending only what the state gave them under the new funding formula.

Beck argued that, because independent high schools were freestanding and not part of a larger school district, they were at a financial disadvantage.

Conlon, meanwhile, took issue with the different standards the senators appeared to be proposing for public and independent schools.

“I fully support the fact that [independent schools] are part of our educational system,” Conlon said, “and yet we are asking a lot of our educational system in this process, and to say one part of this doesn’t have to worry about it is difficult to fathom.”

It was shortly after Conlon spoke that the conference committee disbanded for nearly two weeks. Bongartz said he had been hoping to resume negotiations earlier. He was surprised when he reached out to Conlon to schedule their next session and was told the House was not interested in meeting until the following week.

Kornheiser, too, said an extended break was needed “to give the senators a chance to regather themselves and figure out how they wanted to show up.” But the truncated timeline left the legislature — and the public — less time to review a final reform package before lawmakers reconvened on June 16 to vote on it.

Three Days in June

When the conference committee finally got back to work, independent schools remained at the center of the conversation. The emphasis on this one aspect of the education system left less time to discuss other important topics, Kornheiser said, reflecting on the final negotiations.

“I was certainly very frustrated by the amount of time we spent on the couple of sections related to independent schools,” Kornheiser said.

But negotiations proceeded steadily over three days. Representatives of the Scott administration worked behind the scenes to ensure the final product was one the governor could sign. On June 13, the conference committee shook hands over a shared version of the bill that would go before both of their chambers the following Monday. Scott indicated that he would support the bill, too. The relief in the room was palpable.

That weekend, rank-and-file lawmakers were inundated with emails from superintendents, school board members and constituents urging them to vote no on the bill. Some were focused on the two senators’ connections to independent schools and the time and energy they devoted to the issue.

Burlington superintendent Tom Flanagan wrote to his legislative delegation that “too much time has been spent, especially by the Senate, protecting a small number of private schools that serve a tiny share of Vermont’s students. Meanwhile, the needs of more than 80,000 children in our public schools have been sidelined.”

Scott’s endorsement convinced many House and Senate Republicans to support the bill. In the Senate, which would vote first, Democratic leaders felt they finally had the votes they needed.

But just as Lt. Gov. Rodgers was preparing to call the final vote, Sen. Tanya Vyhovsky (P/D-Chittenden-Central) stood and asserted that the conference committee’s bill should be thrown out because the conferees had violated legislative rules by deviating so substantially from both the House’s and Senate’s versions.

The move was not likely motivated by the fact that the conference bill contained new language, which is routine during negotiations, Dickinson, the Middlebury political scientist, said.

“The reason that these procedural objections loom so large is because of the underlying philosophical divide when it comes to education reform: school choice, independent schools versus public schools,” Dickinson said. “They’re masking philosophical differences about the role of independent schools.”

Vyhovsky’s objection threatened to remove the bill from consideration for a few precious minutes before Baruth successfully moved to suspend the rules so a vote on the bill could proceed.

The final Senate vote: 17-12. The majority of Baruth’s own Democratic caucus voted against the bill — seven for, 10 against.

In the House, members overrode a similar motion to throw out the bill on the procedural objection. An accurate measure of the bill’s final support in each party was obscured by a voice vote, instead of a legislator-by-legislator roll call that would make clear each legislator’s stance. But the subsequent roll-call vote to send the bill to Scott, which handily passed 96-45, drew the support of a slim majority of the Democratic caucus.

Baruth described the bill’s passage as a hard-earned win after months of walking a political tightrope.

“The idea was a broad bipartisan bill, and I’m proud that we got there in the end,” Baruth said. He also pointed to policies in the bill that constrain independent schools: Tuition will no longer flow to out-of-state schools and the 40 or so independent schools in Vermont that get public dollars will be trimmed by more than half.

Olsen, the independent-school lobbyist, went a step further. He characterized the bill as “probably the greatest victory for the opponents of independent schools in the history of Vermont’s independent schools.” He said he anticipated that independent schools with small numbers of tuitioned students would immediately feel the effects of the reform bill, since, starting this month, they will be ineligible to accept new publicly funded students.

Historic academies may also feel a financial impact down the line, Olsen said, depending on how the legislature decides to implement the new funding formula.

Hardy, who ultimately voted against the bill, gave an impassioned speech from the Senate floor before the final vote. She supported many parts of the bill, she said, but the conference committee lost the public’s trust by not representing the Senate’s position in negotiations.

“Some say that the ends justify the means or that policy is more important than process, but if the process is so bad that it leads to a loss of trust from the very people who are the subject of the reform, then a good product will be difficult to achieve,” Hardy wrote in an open letter to her constituents after the legislative session ended.

In her letter, she also took the unusual step of calling for new leaders of key committees before the chamber reconvenes for the second year of the biennium in January 2026. Baruth said he is not considering replacing Bongartz.

The pro tem dismissed the concerns raised by Hardy and others.

“I don’t accept the idea that the Senate lost Vermonters’ trust,” Baruth said. “I think they trusted us to find a bipartisan path, and we did.”

Lt. Gov. Rodgers applauded the bill’s bipartisan passage and stood by the conference committee members who crafted the final version of the bill.

“I think people focused on Beck and Bongartz’s attachment to independent schools too much and didn’t focus on their overall knowledge of education as a whole,” Rodgers said.

But he said the process to get there was frustrating.

“I’m left disappointed with the fact that we didn’t make more progress,” Rodgers said. “I really don’t think much of it was smooth. I think there’s a lot of room for improvement, and I hope we do better next year.”

And Now It’s the Law

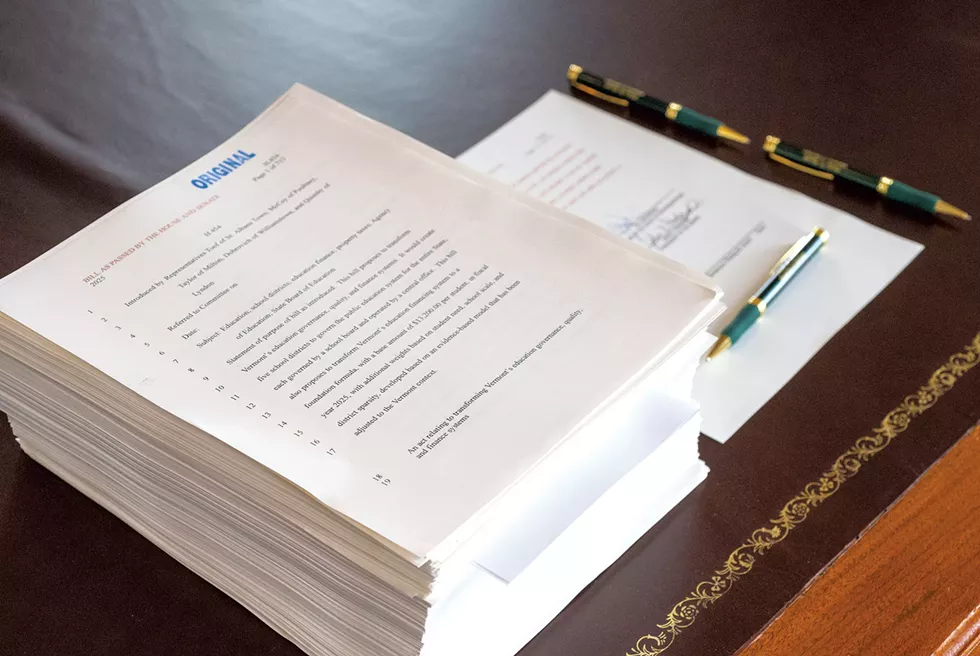

On Tuesday, the mood was upbeat, but not quite celebratory, as Gov. Scott held a public signing ceremony for H.454. Baruth, Krowinski, Education Secretary Zoie Saunders and a handful of key legislators, including five who served on the conference committee, attended. Before inking his name on the bill, the governor, who had pushed hard for the passage of a comprehensive education reform bill all session, thanked the conferees, Baruth and Krowinski.

The legislative session had been “long and difficult and uncomfortable for some,” Scott said, but those involved “were able to come together to chart a path toward a system that better serves our kids, and one that taxpayers can afford.”

Lawmakers who spoke next hit on similar themes: A new, more predictable funding formula would ensure that all Vermont kids, no matter their zip code, have the resources to guarantee a quality education. In the long term, Vermonters will see a decrease in property taxes. Still, they cautioned, the passage of H.454 was just the first step. Many hard decisions await, and debates over independent schools will continue.

The first substantial one will be choosing who will sit on a redistricting task force that will draft three proposals for new school district and supervisory union lines by December. Krowinski, who will choose five of the task force members, said she hopes to name them by early next week. The governor said he will name his one appointee soon.

Baruth, who will help choose the five remaining members, noted that the public-education community would have a large presence on the body. Five of its members are required to be a mix of former superintendents, business managers and school board members. The other six will be legislators. Bongartz has already expressed interest in serving.

Legislators stood deferentially behind Scott as he sat down at his desk to sign H.454. After finishing, he handed ceremonial pens to Krowinski, Baruth and Saunders.

“We are going to have to educate Vermonters on this bill … and be straight with them and be transparent along the way,” Scott said. “And that’s the way we get buy-in.”