Organized to express people’s anger, recent political protests in Vermont have nonetheless looked more like sing-alongs than riots. It’s great that so far they lack violence and reinforce a sense of community. And yet, clever signs and honking cars rarely communicate actual despair.

David Wojnarowicz‘s work comes from a time when political art did do that. It is challenging and shudderingly powerful. The New Jersey-born artist and gay activist, prominent in the 1980s in New York City, made deeply personal art that embodied his rage at how normative society and government conspired to marginalize people. A polymath, he expressed himself in paintings, sculptures, installations, writing, photography, film and performances in a punk band he led — a fever of production cut short when he died of AIDS in 1992 at age 37.

His rage is palpable in the Hall Art Foundation exhibition “David Wojnarowicz,” despite its small sampling. The show contains 15 sculptures and paintings, 11 of which are plaster heads from a group of 23 the artist titled “Metamorphosis.” Additionally, the Reading venue is hosting two screenings of Chris McKim’s riveting 2020 documentary about the artist, Wojnarowicz: F**k You F*ggot F**ker, on July 19 and September 13. The film, also available on the David Wojnarowicz Foundation website, uses much of the artist’s own material and provides invaluable context for the show.

A theme of violence prevails at the Hall: a menacingly suspended life-size sculpture of a shark, a painting of an ocean liner on fire, plaster heads bound with stained medical gauze. It’s an ironic contrast to the setting, a beautifully renovated 19th-century dairy farmhouse and three barns set in 400 bucolic acres. (Beyond their Vermont venue, Andy and Christine Hall renovated a castle in Northern Germany and a shed at Mass MoCA in North Adams, Mass., for their and their foundation’s collections, which number around 5,000 artworks.)

Violence characterized much of Wojnarowicz’s youth, from severe physical and psychological abuse by his father and neglect by both parents to an edge-of-starvation existence as a hustler on New York’s streets starting at age 9. A passage from his essay “Memories That Smell Like Gasoline,” published in 1992, paints a vivid picture: “I had been drugged, tossed out a second story window, strangled, smacked in the head with a slab of marble, almost stabbed four times, punched in the face at least seventeen times, beat about my body too many times to recount, almost completely suffocated, and woken up once tied to a hotel bed with my head over the side […] all this before I turned fifteen.”

That Wojnarowicz was able to channel such experiences into art while remaining nonviolent himself is remarkable. At the Hall, the 96-inch-square painting “Dad’s Ship” (1984), in acrylic and enamel on four joined Masonite panels, refers to his father’s merchant marine job in the boiler room of passenger ships. Wojnarowicz Sr. died by suicide in 1976, when David was 22. Whether the flaming, smoking ship is meant to represent the father’s death, the son’s wish for it or simply an embodied rage, the dead dog — rendered as a small framed photostat riding the clouds in the upper-left corner — is clearly a victim. Its ghostly image draws the eye by its stark contrast with the solid black bulk of the ship.

Wojnarowicz became a prominent voice for AIDS activists, advocating for federally funded research and against censorship of homosexuality in the public sphere. He staged “die-ins” at rallies, in which participants lay on their backs while holding up cardboard tombstones, and created one of the movement’s most visible symbols, a stenciled image of two men kissing.

His gay iconography at the Hall isn’t so straightforward. In the graphic-novel-influenced “Ballet #1” (1982), which incorporates collaged maps and acrylic on Masonite, two stenciled male figures are locked in a violent struggle. A watch, a ring and a wallet flung above the pair suggest a mugging is taking place.

Wojnarowicz used collages of cut-up maps — they also make up the skin of the shark — to question government-imposed order and point out the fictitiousness of borders. In “Ballet #1,” the torn sections of oceans and geological features covering both men’s figures suggest a kinship between them that even economic desperation can’t extinguish — as does the rainbow halo encircling them.

Images of bestiality appear as spray-painted stencils in “Delta Towels” (1983), named for the 51-by-36-inch vertical supermarket poster that Wojnarowicz used as a canvas. The poster’s design is bold and basic, its sale item’s name filling the upper half and the price for a “jumbo roll,” 59 cents, the lower. Atop each half, the artist stenciled a boy framed by a delicately drawn square. Above, he puts his face to a cow’s hindquarters; below, he holds his head under her urine. The layered composition suggests that desire is more complicated than consumerism. The suitability of paper towels for such acts, meanwhile, adds a measure of tongue-in-cheek humor.

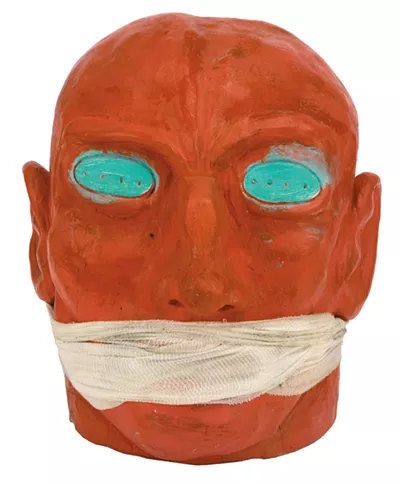

Nothing quite prepares the viewer for the 11 plaster heads of “Metamorphosis” (1984), which are encased in vitrines arranged like bowling pins. The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City displayed them similarly for its 2018 Wojnarowicz retrospective; that show’s cocurator, David Kiehl, said of the setup, “It’s sort of like they’re coming at you.”

Cast from a latex mold and around 9 inches tall, the heads are not quite human, with a brutish shape and, in place of eyes, oval discs punctured with rows of holes. Some heads are collaged with maps or money, including $100 bills — a choice that speaks volumes about an artist who nearly starved several times. Gauze is taped over one head’s ear and used to gag another’s mouth. Acrylic paint renders others in sickly or angry colors; one is painted with what resembles black lava still burning in a network of red-and-yellow cracks.

Wojnarowicz made 23 of these heads to symbolize humans’ 23 pairs of chromosomes. (The rest are likely in other private collections, according to Hall Art Foundation director Maryse Brand.) But their mutilated, Frankenstein-like forms signal horror at how society and government have corrupted and transformed humans into alien-like beings.

Wojnarowicz’s art is a call to others — especially artists — to fight power. “When people put themselves on the line in their work, whether it’s music, writing, photography, painting or whatever,” he said, “they apply a tiny amount of pressure against the system of control that would willingly jump into fascism if there wasn’t enough pressure on its throat.”

As the specter of American fascism looms today, most recently inspiring “No Kings” demonstrations and die-ins around the country, Wojnarowicz’s work has become essential viewing.