Mary Walker faced an impossible choice in the 1850’s: Her children or her freedom?

Walker, born into slavery in Durham, had a rare opportunity to flee when the Cameron family, her enslavers, took her on a visit to Philadelphia. But if she tried to live as a free woman in Philadelphia, she would likely never again see her mother and three kids who she left behind on the plantation now known as Stagville in northern Durham County.

Walker fled.

“She spent the following years of her life hoping and praying and working to figure out how she could get her family free,” Vera Cecelski, site manager of Historic Stagville, tells a tour group of about 40 people on a sunny Juneteenth.

Walker worked as a seamstress and housekeeper and hoped to buy her children’s freedom, or to pay someone to help them escape. Finally, in the aftermath of the Civil War, she was reunited with two of her children after 17 years apart.

Walker’s story, like the story of Juneteenth itself, is one of struggle and celebration held hand in hand. It’s also one reflected in the experiences of many enslaved people in this state’s history: Cecelski notes that, at the time of emancipation, about one in three people in North Carolina were enslaved.

“We often hear the story of emancipation as a national story in the scope of this broad conflict of the American Civil War, but we really wanted to look at these intimate local stories of—how were real families here in what is now Durham County experiencing the transition to freedom? What were their dreams and their worries in those first few months of freedom?”

Stagville, which was once part of the vast Cameron family plantation that spanned 30,000 acres and was home to about 1,000 enslaved people at its peak, is now a state-owned historical site. On Juneteenth, tours that normally cost a dollar or two are free, and hundreds of locals make the pilgrimage to walk the land where generations of enslaved people lived and labored.

Cecelski says the site draws two to three times as many visitors on Juneteenth as it does on an ordinary weekend day.

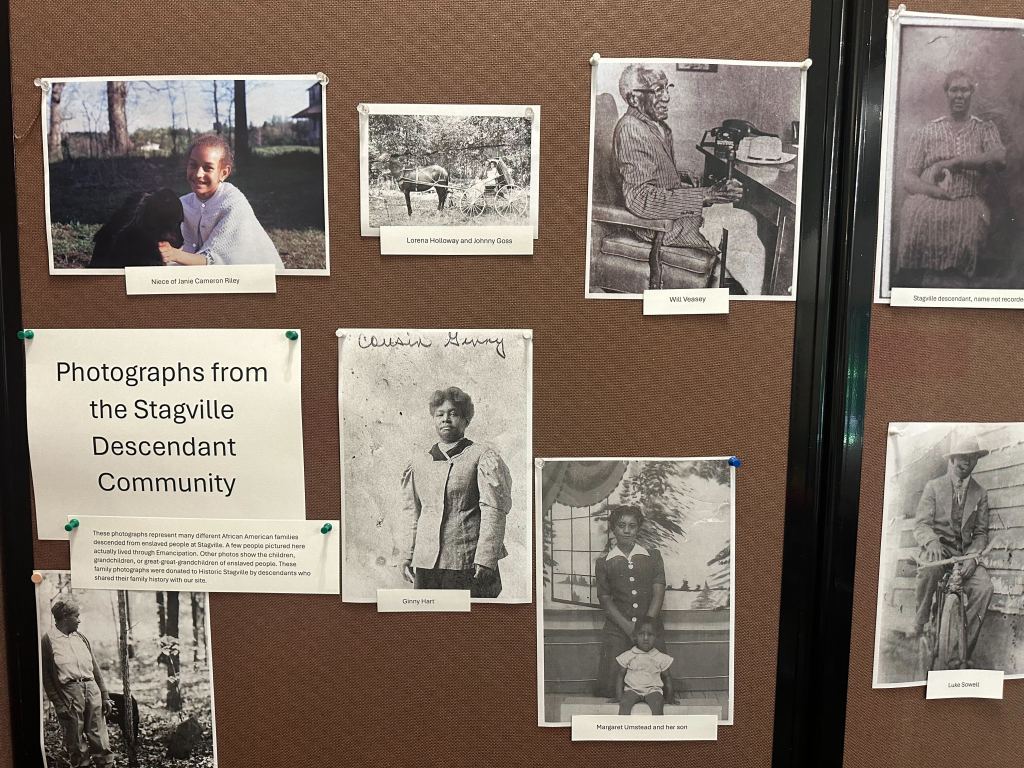

Stagville isn’t a dusty museum, though. Cecelski’s tour is built on the fact that the descendants of the people who were enslaved there are very much alive and involved in how Stagville presents its history today. And after the day’s tours are gone, some of those descendants will gather on the land to mark another Juneteenth.

Cecelski takes the tour through a row of sparse two-story wooden houses that held 20-30 enslaved people each, packed into claustrophobic rooms, when the plantation was active from 1771 to 1865.

In between two of the houses, Khadija McNair’s two daughters play in the shade of a 200-year-old walnut tree. The tree, thought to be the oldest at Stagville, was planted around 1818, when Mary Walker was born into slavery on the plantation.

As she juggles two pink water bottles and manages her young daughters (“Please don’t swing that stick around,” she warns one of the thigh-high youngsters), McNair tells me that she brought her daughters to Stagville on Juneteenth because she was born and raised in Durham but didn’t learn about the plantation’s history until she was an adult.

“Being from Durham, being Black, I want them to know that this history is a history of us and our people, and they were strong so we can be strong,” McNair says. She previously worked at Historic Stagville, and now works at Freedom Park in Raleigh, which will have its own Juneteenth celebration this weekend.

Against the trunk of the walnut tree, McNair and her daughters left three pink and white roses.

“I want my kids to know this is a day to reflect and honor the struggles, the violence, but also the resilience of our ancestors,” says McNair. “It’s also a holiday for celebration.”

Reach Reporter Chase Pellegrini de Paur at [email protected]. Comment on this story at [email protected].