On February 1, 1943, a 28-year-old graduate of Lyons Township High School was scheduled to relax on one of his rare days off as an Army Air Corps bomber pilot in the European Theater during World War II.

But one of the pilots scheduled to fly that day was sick, and someone had to take his place. So he volunteered.

That selfless act cost Major Robert E. Coulter Jr. his life. He’s memorialized in the name of La Grange’s Robert E. Coulter Jr. American Legion Post 1941, but Bill Kiddon, post commander, wants to make sure the story of his heroism isn’t lost to the passage of time.

“Probably the first generation or two of legionnaires know of his story,” Kiddon said during a May 22 presentation to the La Grange Area Historical Society. “But today’s generation of legionnaires don’t know this story.”

Kiddon spoke for 45 minutes to about 50 people at the Historical Society’s Vial House Museum, 444 S. La Grange Road. The presentation included footage of air combat between American B-17s and Luftwaffe fighters filmed by an embedded Air Corps journalist. The recording included the scene of a badly damaged bomber plummeting to the ground as two parachuted flyers escape.

Coulter attended Ogden Avenue School and graduated from Lyons Township High School two years ahead of his sister. He went on to earn an engineering degree from Purdue University.

Kiddon related how Coulter, in October 1942, was among the first pilots to fly unescorted bombing missions, because the fighter planes at the time didn’t have the fuel capacity to accompany long range bombing missions. He logged 25 missions, a marker used by the Army when pilots could be relieved of active duty. But Coulter refused to rotate out of combat.

He flew 35 missions in all, bombing Nazi submarine pens, destroying a Nazi U-boat base, and leading critical bombing missions in North Africa that helped prevent the Nazis from seizing critical oil fields.

“On February 1, 1943, he was not supposed to fly that day,” Kiddon said. “When he got down to the briefing room, he found out there was another pilot that didn’t get out of the infirmary and couldn’t fly. He was grounded that day, so Coulter volunteered. He said ‘I’ll go up.’”

After completing a successful bombing run over North Africa. Coulter’s plane was hit head on by a Messerschmitt Me 109.

While nobody will ever know what caused the Luftwaffe pilot to steer directly into the formation, the collision ripped off one of the bomber’s wings, causing it to spiral downward in flames.

Three crew members — the bombardier, navigator and gunner — parachuted to safety and wound up in a German prisoner of war camp.

It wasn’t until August, 1943 that the wreckage of the B-17 was found just off the shoreline of the Mediterranean Sea. It wasn’t until then that Coulter’s family got the telegram dreaded by so many families during the war, that their son was no longer missing in action, but killed in action.

Coulter wasn’t the only family member to contribute to the war effort. His father, a member of the Federal Reserve, was involved in the war bond drive. His mother wrapped bandages for the Red Cross and then became chairperson of Red Cross fundraising and his sister married another pilot.

“It was a family of service,” Kiddon said. “They all pitched in — not unusual for the Greatest Generation.”

Kiddon noted that Coulter was keenly aware of world affairs in the late 1930s as Nazis rose to power in Germany.

“He told his parents ‘we’re going to war,’ and wound up enlisting in the Army Air Corps in 1939, around the same time Hitler invaded Poland,” Kiddon said. “He was trained to be a pilot in Texas, and ultimately flew the famous B-17 Flying Fortress.”

Within three years, Coulter was piloting a B-17 in Europe. As was the custom in those days, Coulter’s plane had what came to be called “nose art” on the front of the plane. His was “Bat Outta Hell.”

Kiddon stressed that the story of Coulter, and all the other pilots in the war, was also a story about the B-17 Flying Fortress and the challenges that came with serving in one.

“This was not a pressurized airplane,” Kiddon said. “At 25,000 feet, it was 10 below zero; at 35,000 feet, it’s 40 below zero. And this plane flew at 35,000-feet, with no bathrooms and no heat.”

Kiddon said the Boeing Company built 12,700 B-17s during the war — at its peak, averaging 16 per day — and roughly 80% of the warbirds were built by women.

Among those listening to the presentation were Tim and Kathy Calvert, who found out they live in the former Coulter family home on North Waiola Avenue.

“We were traveling and came home and somebody had left an article on our front porch,” Kathy said. “If you go up our stairs, up to the attic — we have a walk-up attic — the initials R.E.C. are carved into the side,” Tim said “It’s kind of an honor to live there.”

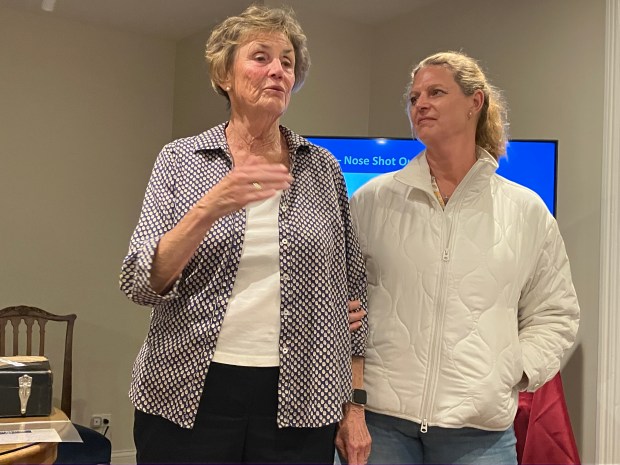

Robert Coulter’s niece, Bonnie Williams, born six weeks after he died, was on hand to share family memories.

“It affects the whole family, the whole community, everybody who knew him, when somebody dies like this,” she said.

Her uncle’s legacy always resonated in their family.

“When they spoke of him, they spoke of all the wonderful memories,” she said. “There was never any sadness or remorse or regret. They were very proud of him. I can’t imagine losing a son, but it was a different time. He was a good person.”

But even for Coulter’s family, the efforts of Kiddon and the American Legion to keep his legacy alive are essential.

“To put it all together brought the whole thing to life, things that we didn’t know,” Williams said. “I learned more last year when he did the first presentation than I ever knew about it.”

Hank Beckman is a freelance reporter for Pioneer Press.