I live in an apartment building in downtown Durham that houses more Duke University undergrads than any other category of person—a friend once characterized it as an “adult dorm”—so it wasn’t all that surprising when, last week, I found a cute little table in the trash room on my floor. At the end of the school year, a lot gets thrown away.

The table was in great condition, amid stacks of linens and unopened boxes of date-nut energy bites. Made from clear acrylic, its edges were tinged a neon lemon-lime color that changed with the light—sometimes appearing to be part of the acrylic itself, other times a reflection dancing along its curves.

I took it home. When I looked it up online, I discovered it costs $900. (Shipping cost: $199.)

That was retrieved from the trash room at the end of my hall, where you put things down the chute. The real gold mine is the ground-floor room that the chute empties into, accessible by one of the elevators.

This is where, around graduation each year, you can find dozens of vacuums, Keurigs, stainless steel trash cans in every size and shape imaginable, mattresses, mirrors, and enough luxury goods to make a reseller weep with joy. The first time I went down there, last week, I noticed something neon in a tote bag and pulled out $395 Balenciaga slides. Nearby were $980 Valentino sneakers—worn, but definitely wearable. More than $1,000 of Lululemon workout clothing tumbled from a bag onto a couch.

You don’t really have to do any digging—most of the stuff I’ve gotten was sitting on top of discarded furniture. But you do have to rush. After I took the Lululemon haul upstairs, I returned to find city waste workers loading things into a garbage truck, off to a landfill. The volume of discarded clothing seems consistent with generational trends: textile waste in the United States went up by more than 50 percent between 2000 and 2018.

Not every treasure is a flashy brand-name item. I also recovered pink satin pajamas that I remember seeing on someone attending a pajama party on my floor, and a ruffled olive-green Top Gun romper from a Halloween event. (Sadly, there was nothing from the risqué Dr. Seuss party.

A few months ago, a fire alarm went off, and it became apparent just how much of the building is occupied by Duke students, as nearly everyone except me, my roommate, and a family with two young kids was drunk and dressed in Cat in the Hat costumes.)

It feels wrong for this much stuff to have been thrown out in the first place, but it also feels mildly wrong to take it. So it was nice to get intermittent reassurance from my building’s maintenance man, Eric.

The first time, as I was scurrying back to my room, carrying an upholstered kitchen chair that my cats now spend all their time in, I passed Eric in the hallway. He asked me how I was.

“Just doing some scavenging,” I said. I must have looked guilty, because he said, “That’s OK.”

A few days later, I was again downstairs in the big trash room when Eric walked in. I moved to leave, feeling awkward about being caught again. “You’re welcome here anytime,” he assured.

The sheer volume of valuable, usable things being discarded boggles the brain, particularly when it comes to items like clothing with the tags still on and unopened, unexpired food items.

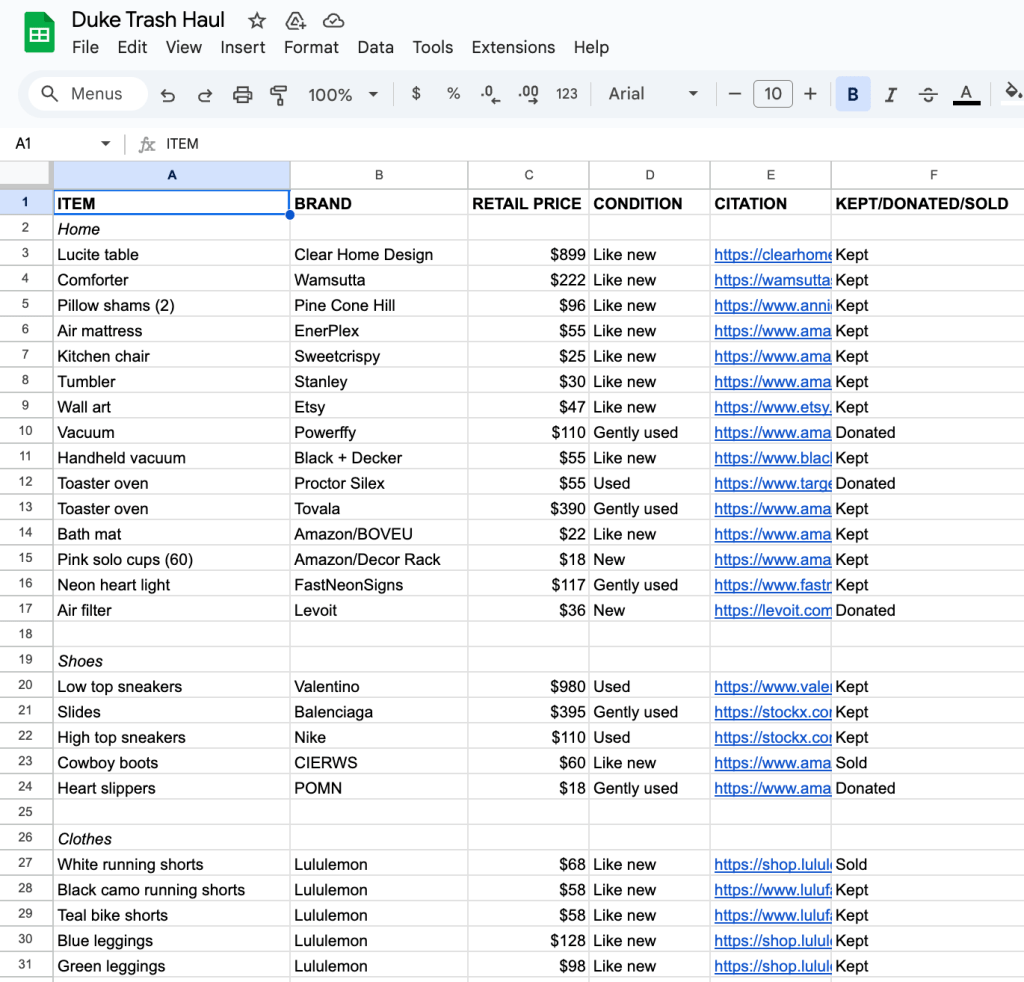

In trying to make sense of things, I made spreadsheets.

The first tracks the prices and brands of the items that I kept, donated, or sold. The total value came to around $6,000, not including several items I couldn’t find prices for.

The second spreadsheet compares Duke’s donation collection data with that at other universities, in an effort to understand whether this college-town phenomenon is universal. I gathered publicly available data from university websites and press releases, supplemented by direct inquiries.

Duke told me their “Devils Care Donations” initiative collected 32,000 pounds this year through partnerships with TROSA and Goodwill. Ali Harrison, senior associate dean for residence life, says that the university places donation bins in every residence hall on campus, plus off-campus Duke housing like Blue Light and Swift Apartments. Harrison also notes that “Duke students who live off campus in non-Duke housing can schedule a TROSA pickup for large or bulky items and large donations.”

I emailed six universities, asking about their donation programs and collection data. Most didn’t respond or declined. One directed me to a public web page. Rice University, whose “Give a Hoot! Donate Your Loot!” campaign recently won a statewide award in Texas, sent a detailed response. They reported that they collected around 11,000 pounds of “durable goods” from students this year. (Rice has around 9,000 total students, with roughly half undergrads and half graduate students.)

Rice’s approach is to implement collections every semester, not just during spring move-out. “By maintaining a consistent presence throughout the academic year,” a spokesperson wrote, “the campaign has become a familiar part of the student experience,” helping students plan ahead to donate rather than discard.

Looking at the data, Duke’s per-undergraduate donation rate (about 4.9 pounds) is comparable to that at other wealthy private universities like Princeton (7.6 pounds) and Georgetown (6.1 pounds). Duke actually outperforms some schools with similar student demographics like the University of Chicago (0.8 pounds) and Northwestern (0.9 pounds). Most large public universities hover around one pound per student.

The emotional reality of my salvaging week was harder to organize into neat columns. For one, I started feeling like everything I own is shitty. When you’re pulling something out of the trash, it doesn’t feel like it’s going to be a luxury item, so at first, I didn’t think much of a comforter I salvaged and offered it to my boyfriend, who’s always looking for blankets for his dog to lie on. After looking up the cost ($222) and thread count (600), I went back on that offer and replaced my existing comforter with the salvaged one. (The next day, my boyfriend found his own down comforter in the trash.)

Most items I salvaged were like new, but some needed attention. It felt good to wash, clean, and mend things—removing stains from a blouse, fixing belt loops on black slacks. But then futility would set in. I tried to get the stains out of a pair of muddy Nike high-tops with floral embroidery, using a Solo cup I salvaged as a mixing receptacle to stir together baking soda and hydrogen peroxide into a thick paste, but even after slathering it onto the shoes, the stains persist.

I also spent some time scrubbing a toaster oven, only to go back to the trash room a few days later and find one that’s cleaner and fancier. Retail value: $400.

In what would become my final scavenging trip of the year, I tried carrying too many things at once—a handheld vacuum, an air filter, some velvet hangers—and dropped the toaster oven, which splashed water all over me from its steam reservoir.

Sometimes it’s a spill that does it. I stood there, damp, surrounded by other people’s discards, feeling ridiculous. My apartment was already filled with rescued items. I went home, found that the air filter didn’t fit my unit, and cried.

The next night, my cat jumped down from the salvaged chair he loves, used his litter box, and then kicked litter everywhere—as per usual. Managing litter has been an ongoing struggle. Various vacuums have proved too weak or too bulky to reach the corners behind the box, so I usually just sweep with a handheld broom and dustpan.

But as I bent over with my dustpan that night, I remembered the handheld vacuum I’d salvaged just before dropping the toaster oven. I’d found it with its charging cord sitting right next to it, still coiled neatly with a twist tie.

I grabbed it from my pile of findings and turned it on. It was the most powerful little vacuum I’ve ever seen, its pointed nose perfect for crevices.

Reach Staff Writer Lena Geller at [email protected]. Comment on this story at [email protected].