Since 1996, when the Academy of American Poets began calling April “National Poetry Month,” this country’s writers, publishers, libraries and literary organizations have used the moniker to celebrate the art of verse in many ways, including readings, collaborative performances, conferences, workshops and awards.

In Vermont this month, whole communities such as “PoemCity” Montpelier and “PoemTown” Randolph are presenting poetry on stages and in broadsides on store windows. And the finalists for the 2025 Vermont Book Awards have recently been announced. Seven Days previously featured reviews of award-finalist poetry books by Alison Prine and Kellam Ayres. Here we consider the work of the other two finalists for the Poetry award, Julia C. Alter and Margaret Draft, along with the latest from Stephen Cramer.

Some Dark Familiar, Julia C. Alter

Williston poet Julia C. Alter’s first book dares to examine the bleaker, more exhausting impacts of maternity, including postpartum depression, bodily changes and pain, the stark loneliness of new parenthood, and a hunger for “Non-Monogamy,” a phrase she uses in the titles of six poems dispersed through Some Dark Familiar.

Given how idealized mothering is in our public rhetoric, Alter’s rogue candor can be shocking, while her phrasing is often mesmerizing. The poem “Who Makes Milk?” begins:

Cows, I want to say. But I say

mammas, I say mammals.

Whales, even. Milk is made

by a wound, or that’s how

I made it for you—the un-making,

the un-drinking. The blue empty, blue

translucent. Sucked teats make it.

Beasts make it. Other mothers.

Better mothers…

Alter’s protagonist both courts and flees tenderness. In “The Excavator,” the speaker says, “I am climbing a hill / holding hands with a man / who isn’t my son’s father. Tonight, / the moon is a wrecking ball.” In “L’Oeuf Chaud Froid,” named for a recipe on a TV cooking show, she says, “I’ll never forget the sucking / of the machine when you couldn’t. / I’d grind my teeth / like I was coming down / off ecstasy when the only thing left / was chills, the useless hollows / of a body shitting and shivering, / feverish and frigid and fragile / as 4 am, / as baby, / an egg shell / opened up / and ready / to be filled.”

Alter plays with the kinship between “moth” and “mother,” evoking a beauty that’s vital but terribly flimsy. Violence hums and buzzes in the offing, with poems that muse on a child’s “split lip” or a family pet’s murderous act: “She’s a golden doodle / with a dead bunny in her maw. / She doesn’t drop it at my feet. / I muscle her jaws apart and reach in” (“Daisydog”).

Individually, these poems have striking effects and beautiful moments, yet the reigning tenor of Some Dark Familiar is grim. This lends a numbing unity to the collection. The penultimate poem, “Owl Hill,” reaches for calm and some form of re-enchantment, but the final poem is weirdly, casually sordid. Shall we conclude that life as lover or parent is mostly an ache?

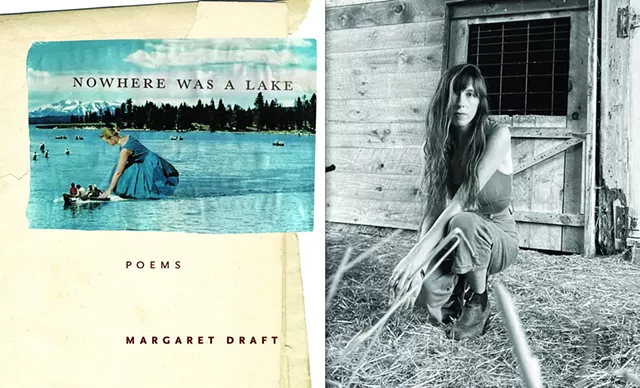

Nowhere Was a Lake, Margaret Draft

Bennington poet Margaret Draft shares with Alter a fascination with the carnal astonishment of bodies beside one another and the allure of what some would call infidelity. In “Dear Metamour,” Draft’s speaker addresses a lover’s wife: “When he arrives a minute after midnight, / smelling of me, musk & honey / … / please, know that I have also slept alone / in the same remote home with my husband.”

These are lines from Nowhere Was a Lake, Draft’s extraordinarily accomplished first book.

Of eros remembered, do we ever tire? This is the opening of “Plain Meeting House Cemetery in West Greenwich, Rhode Island”:

Both the dead and the living. She is straddling

him in the graveyard, his back pressed against a grave.

Where did they go when they wanted to go

or thought to go wherever they went together to go?

She takes off, dancing across

the dirt path, and he follows.

They pretend they don’t know what the other person wants.

They are resting under the gentle boughs of never knowing.

Verse is more gestural than prose, and not only are Draft’s lines muscular and flexible but she also keeps finding ways to use the spaces between lines and stanzas for temporal, tonal and narrative leaps. She trusts silence as well as words, allowing the not said to be as substantial and audible on the page as the said aloud. Listen to “Purview,” quoted whole (though the nuanced indents are hard to convey here):

On the one hand, I cannot unsee the things I saw.

On the other, I cannot see the things I saw in the same way again.

That was then.

For the time being, I have seen all that I possibly can.

I can see that now.

Draft’s method is to convey enormity with brevity and restraint. Along with alternating black type and the pages’ empty spaces to guide the eye, she uses arresting syntax to catch a reader’s ear. Consider these inversions, angling out of our everyday vernacular: “Once was the poet from Kansas / kindly cautioning—,” and “How fragmented. And of fragments I have given some thought.”

Sometimes, as she speaks of silence, she makes silence corporeal and immediate. Here are the first four stanzas of “The Doe”:

Feasting on a small blade of grass.

Sensing something else

breathing in the shadows,

she stops.

She sees,

what does she see,

or not see, that I recognize,

or try to, in her, also?

June came and went.

In poems like these, we can’t separate the inner and outer, what we see and what sees us, what we touch and are touched by. Moreover, Draft’s poems are funny in ways not easy to explain, as in “Lucid Dreams & Small Nightmares”:

Every object in the room,

plenty and too much.

Made to be unmade.

Even the bed.

Especially the bed.

At the conclusion of this quietly rapturous book, many readers may circle back to read again from the beginning.

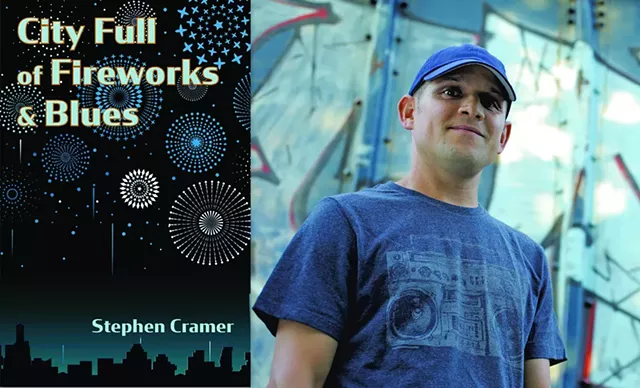

City Full of Fireworks & Blues, Stephen Cramer

Burlington poet Stephen Cramer’s The Disintegration Loops was a finalist for the 2022 Vermont Book Award. While his most recent book, City Full of Fireworks & Blues, isn’t under consideration for this year’s award, this 2024 release is so smart and enjoyable that it warrants acknowledgment here as Vermont regales its poets with the brief annual hubbub of Poetry Month.

In this book, coherence and continuity arise from how all the poems are very much alike — which is not to say that they’re repetitive but that they’re kindred in length and style and texture. A reader can move happily from piece to piece like running a relay or frolicking in waves.

Cramer builds his poems in riffs and crescendos, alluding to jazz musicians and directly emulating their sonic verve. In “Temple,” he writes:

you know that breath just after the spiraling

birdcall & before

the canyon’s response,

the moment between Diz’s clowning & when Bird

lifts his plastic

horn & cuts him

with a melismatic rush honed to a scold, metronome

crushed by velocity…

I’m trying to learn

to dilate those seconds…

For Cramer, sensory experience is an accelerant, igniting in words. He seems — he sounds — endlessly amazed by the world he’s thinking about and walking through. These poems are lucid annotations on this and that, whatever turns up.

But he’s not confined to the merely real. Of “My Angels,” he says, “After all that listening / to their pure soprano / voices, it’s time to rewild, / time to reset the cerebrum / & musculature back to astonishment.”

Sometimes he’ll pivot a poem on a whimsical notion, but whimsy that’s torqued, as in “Ledger”: “somewhere there’s a ledger / that tells us / how much of our breath // we’ve given to dispute, / how much to song.”

In “Hollow,” he considers the emptiness from whence reality springs:

It’s why

I’ve been trying

to understand

that the world can be

both mango & knife edge

not with my brain

but with my heart’s

four hollows,

the places where my heart

isn’t, the places

that need

to be filled.

Who would have imagined, after all these centuries of poets rhapsodizing, that someone would devise a fresh way of characterizing the human heart?

There are more instances of “we” than “I” in City Full of Fireworks & Blues, and Cramer’s verbal inclusivity is welcoming.

Hear the joy he finds in “Bioaudioluminescence”: “Certain // notes say how the heck / can you be so down // when this day / should be hyperbolic? // You know, right now / we’re as far from death // as we’ll ever be.”