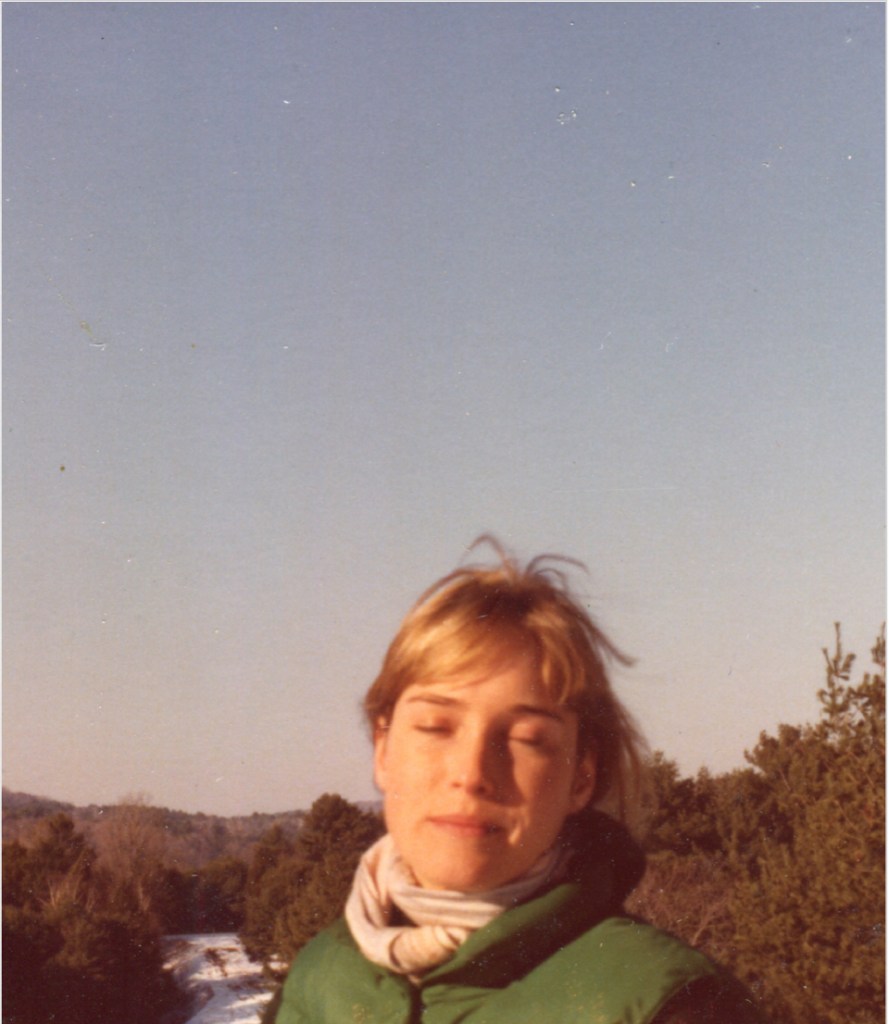

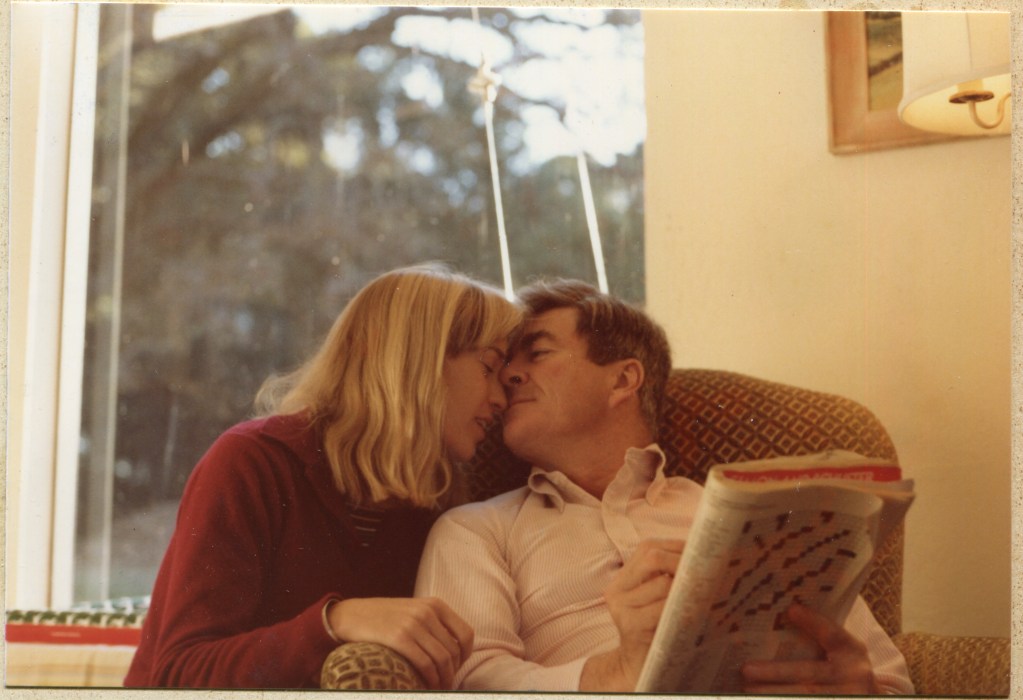

When they tie the knot in 1982, Helen Hooper and Pete McCloskey are both a likely and utterly unlikely match. Pete is an anti-war Republican congressman and divorced father of four. Freespirited Helen, a political aide in his office, is 26 years his junior. Both share a lust for life and fierce love of California, in all it is and could be.

In Helen and the Bear, Alix Blair’s solo debut documentary screening at Full Frame Documentary Film Festival this weekend, these past and present tensions are given artful space to breathe. It’s a beautiful film, activated by ephemera like home videos, archival footage from Pete’s campaigns (Pete’s nickname is “the bear”), and Helen’s tall stack of diaries.

Over the years, Pete’s restless charisma is absorbed by the public life he is devoted to. Helen has a harder time with the identity she’s been assigned, as a politician’s wife, and with finding a destination for her own charisma and restlessness. “Whenever he’s being interviewed, I disappear,” Helen says at one point, referencing the campaign trail.

Helen is private, but she doesn’t want to disappear. Throughout the marriage, she maintains a gruff independence—her character reminded me a bit of Frances McDormand’s Fern in Nomadland—that includes a years-long affair with a woman, which she eventually breaks off. (It’s intimated that Pete also has his own surface-level liaisons.) The pair seem to make peace with this part of their union: “Marriage is full of contradictions,” Helen says.

Years go by and the couple grows old together—or, old and much older, with Helen as Pete’s caretaker—in a loved, lived-in ranch house filled with old couches, horse blankets, stacks of magazines, and a truly prolific number of geriatric dogs. This is where Blair, Helen’s niece, comes in: A filmmaker and former Durham resident, Blair moved to California in 2015, where she began to spend more time with her aunt and uncle, eventually beginning to film their life—playful and devoted—together. By then, Pete is in his mid-nineties and, after a forty-two-year marriage, a twilight life without him looms in Helen’s near distance. What will it look like? Who will she be?

Intimate cinematography and adventurous editing stitch together Helen and the Bear; it’s stunning, really, in a way I find hard to articulate. Likewise, I find its searching core hard to describe. Most reviews of the film have described it as a great romance, a testament to weathering the long haul, but I was less sure of that takeaway. Helen and her bear clearly have deep love for one another, but some wondering aches about past choices are not resolvable. Maybe that’s why the documentary is so good: It touches on a universal ache.

Ahead of Full Frame, the INDY spoke with Blair and one of the film’s producers, Durham resident Rebekah Fergusson, about making Helen and the Bear.

Can you walk me through the film’s timeline of when you first pitched it to when you wrapped up?

AB: My first film, which I made with two Durham folks—Farmer/Veteran—was just ending its festival run, and I had followed my partner out to California. It was the first and only film I’ve ever made. I didn’t go to film school and learned through trial and error, a lot of error, you know, learning from friends or with friends. I got out to California and had, like, four part-time jobs and was deeply grieving leaving North Carolina. I wanted to be with my partner, but I thought North Carolina was where I’d grow old, have kids, and live forever. I was trying to figure out what the new creative thing would be, being in a new place, with a lot of mourning for what I had let go of.

I did not have a relationship, really at all, with my aunt and uncle, and all of a sudden they were about an hour drive from where I was living, pretty much for the first time in my life. It was 2015, so energy was happening, anticipating the 2016 election. The film started with me thinking it would be a short, deeply rooted in the story of political nostalgia—like, who was Pete? What did he represent that is completely lost from politics today?

Almost immediately, within six months of filming, I found myself pretty bored by going to all these political rallies and was so much more interested in Helen’s story—knowing some family gossip of experiences she had had during her marriage and how it was mirroring my own tension of wanting to be in my relationship but being very aware of what I was giving up for it. The personal became the thing I was most devoted to seeking answers to.

About a year in, Helen gave me her diaries. It started as a library lending thing: She would only let me take one, and I’d have to take it and I’d read it, transcribe it, and then I’d bring it back and get another one. Eventually, she was like, ‘Okay, just take them all.”

I was going to ask how you made the initial pitch to them, but it sounds like it was something that evolved—so, how was that evolving pitch with your aunt and uncle? “This is a political doc” is a very different thing from “this is a really intimate look at your marriage.” How did those conversations go?

AB: I have to say, it was pretty easy. Pete is used to the spotlight, so filming him was no big deal in terms of his comfort and following him around. Helen was always—in the seven years of actively filming, even in our final interviews, she was always like, “Do I look here? Do I look here?” It did get to a point where I became a little more invisible.

Helen was used to being the person on the side. She’s a very confident person. She’s very fierce, but she’s been behaviorally practiced at being the wife of Pete McCloskey. She introduces herself like that: I’m the wife of Congressman Pete McCloskey.

I was always very transparent with them. Even at the beginning, I knew I wanted to make it about both of them, even though I thought it was going to be focused on him. I was very curious to look at her role in that. It wasn’t like, one day I woke up and was like, “Oh my god, it’s about the wife!” I was always committed to, ”How are they doing it together?”

As I had more and more conversations with Helen, I got brave enough to admit to myself: “This other story that maybe is less sellable superficially is actually the one I care a lot more about.”

As I had more and more conversations with Helen, I got brave enough to admit to myself: “This other story that maybe is less sellable superficially is actually the one I care a lot more about.” There were never “gotcha” moments, though—Helen and Pete were deep collaborators on the story. We had a lot of conversations, especially as the film got closer, about what it will mean to make her life so public when she’s been so private.

I was very clear that I would have the final say—she’s not listed as a director—I would be making the choices [but] I wanted her to feel a lot of agency and inclusion, that this story wasn’t being done to her, like there was a way that she was very much involved and cooperative in how we were making it.

It seems like something she’s contending with is, “What are the choices we make, and what are things that just happen to us because we are in this assigned role?” I found her to be such a compelling subject.

AB: The director that made [the TV series] I Love Dick, Joey Soloway, they have a quote that I taped to my editing bay—I can find the exact quote. [Editor’s note, exact quote here: “Were any man to look at this woman, they would say, “She’s crazy, she’s a slut, I don’t like her,” but when a woman reads the book, she says, “She’s my hero, I am her, and the more they don’t like me, the further this thing goes.”]

One thing we really were joyfully trying to figure out in this film was how to talk about time and how time is not linear—how it’s circular or seasonal, especially a feminine experience of time; how we inhabit all our past selves at any given moment. We thought a lot about how to make ghosts work in this film. The hints of magical realism in this film try to figure out how we talk about time. I think in terms of that quote—this expectation that you’re supposed to be linear, and you’re supposed to grow up and be a certain way, and yet we’re just all messy and figuring it out all the time. That’s one thing I love about the film, its ending on: She doesn’t know what’s gonna happen next. Any of us don’t.

How she acts like such a teenager is so true to who she is. I’m like, “I feel like I’m 14, you know, with two kids and a house and jobs and husband,” you know? I think the way she embodies contradiction is so beautiful. I crave those stories [about people who] don’t have it figured out.

RF: There is beautiful poetry in the way that Helen has lived her life. Part of it is that contradiction and that raw honesty. We had the gift of showing that through her words, like her journal entries, which was amazing.

And then we had this other beautiful gift, which was that Alix had been documenting them for so long. We had layers of different eras. We had archives that went back to Helen and Pete’s childhood. We had archives of Pete’s political career. We had some early shooting that Alex had done that almost looks like home videos in the film. And we could see these actual visual repetitions, these patterns, emerging.

Alix and Kat [Katrina Taylor], our editor, did this amazing job of weaving through that footage and using it visually to connect these different eras, which helps create that sense of the past and the present woven together.

That ties into what I was going to ask next—how did you go about making decisions between filming in the present and all this archival footage? What was your philosophy of time?

AB: Kat’s brain as an editor—the way she sees connection is incredible. When she came on, she had maybe three months where she just watched all the raw footage. She watched all the archives even before she came into the creative process.

The beauty of being a director/cinematographer is that I can keep it small. It’s just me. I have the ideas, I can film as I go. The danger in that, especially, I can take things for granted. I can fill in details that I haven’t filmed but know because I lived it. I think any editor-director relationship is this beautiful balance, where they’re coming in as the audience proxy to be like, “If it’s not there, it’s not there.”

RF: What was interesting in the final edit, what you have—through a lot of trial and error, a lot of work with Kat and myself and other people, and being a part of those creative feedback sessions—is these sequences that give people just enough at just the right time that they might be having questions coming up, like, “Who is Pete and what is his history”? Having some sequences when he goes out on a trip and you’re flashing back into his political career, those sequences are very sparse in a beautiful way.

Instead of giving people this, “Well, once upon a time there was this politician” and playing out this long story, it’s more impressionistic. There was a lot of thinking about the dips into the past as moments that were really important to the film. They had to be powerful, but they had to be done in this in a way that, you know, we were going in and coming back out in a poetic way that didn’t overinundate with people with information or live in the past too long.

AB: If anything comes through for your story, I just want to deeply honor that part of making this film was a desire to be deeply creatively collaborative with my team. One thing I’m most proud of in this film is who I got to work with, and how the film is as good as it is, because there were multiple voices giving feedback.

Your team mostly seems made up of women.

AB: Yeah, except for the composer and sound designer, who are incredible men. One experiment I had was to see what it would be like to make a creative sense with all women, just to get more data, and because it’s a deeply feminine story.

What things changed during filming? How did your relationship with Helen change?

AB: Even now, we text all the time, and that’s so cool. Pete passed a year ago, and my mom and I and Helen were all with him the day before he passed in the morning, and we were there the whole day before.

I feel deeply interconnected with Helen’s life in a way. [Before our relationship was] at best superficial, like a cool aunt you have in your life that you wish you saw more. This film was an excuse, in a way, to participate in their life and bear witness to it in a way that feels really meaningful.

A question we get sometimes is, Helen is so private, why would she want to have the film made about her? There’s that quote in the film from her journal, where she says, “I feel loved by many people, but I still don’t feel known,” which is absolutely one of my favorite parts of the fill—that idea of, you can be so deeply loved, but still feel this absence of being known.

Rebecca has heard this a lot, but when I was growing up, when I was in my early 20s and Helen was having one of her long-term affairs, family members of mine would call her selfish. And I remember at the time not thinking about it a lot, but then as I was making this film, really being curious, of like, how the word selfish is weaponized against women.

If you’re a handsome, charismatic politician and you have a bunch of extramarital affairs, it’s kind of no big deal, right? It’s expected. But for Helen to have extramarital affairs and be deemed as selfish—that was something I wanted to interrogate.

Like, why is a woman choosing her own needs when she’s very loving to her partner and they’re figuring it out together—why is she selfish? You asked something that changed—I think that in the act of making the story and bearing witness to their relationship, I have changed, too, to be someone that is much more forgiving.

RF: The reason that I wanted to work on this project is because as a gay person myself—married to my wife, living in Durham with our two kids, and having grown up in the ‘90s and coming out and all of that on my own journey—I just so appreciated how matter-of-fact Helen is about the way she observes her sexuality and her gender.

You know, it’s just: “When I was a child, I self-identified as a boy.” Very simple and direct. And the way that she carries those things, I always thought she was just such a queer badass, and that’s one of the reasons that drew me to her as a character. I think that’s coming out with our audiences—straight, gay, in-between—is the way that she’s in touch with that part of herself.

Follow Culture Editor Sarah Edwards on Bluesky or email [email protected].