We can thank “The Marchioness,” a work by Nigerian American artist Toyin Ojih Odutola, for helping to bring one of the most exciting exhibitions of contemporary art to the North Carolina Museum of Art (NCMA) this spring: The Time Is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure.

A loan request from London’s National Portrait Gallery for “The Marchioness,” where The Time Is Always Now exhibition was first staged, led NCMA director Valerie Hillings to ask if the show could come to North Carolina after its second stop in Philadelphia. Lucky for us, the answer was yes.

“The Marchioness” is a portrait—created with charcoal, pastels, and pencil—of an elegant Black woman in a silky, white pantsuit with a fur stole draped over her arms, sitting in a lavish room. It’s part of a larger series that depicts two fictional aristocratic Nigerian families whose world offers an alternative to the present—one where British colonial rule and the transatlantic slave trade never happened. The marchioness’s skin is created using a distinctive technique Odutola calls “mark-making,” in which the artist meticulously layers marks to build up a luminous dark surface.

Odutola has talked in interviews about wanting people to “travel” through the layers of her subject’s skin—which is why her work is at home in an exploration of what it means for Black artists to reframe the Black figure.

As the title of the show suggests, The Time Is Always Now collapses past, present, and future into a single moment—now—suggesting both transmutation and time travel. Odutola’s work, like many of the other works in the exhibit, involves both: her art offers an alternative past that transforms our sense of what is possible in the present.

“The speculative can be a bridge and the process of creating it an emancipatory act,” said Odutola, in regards to her work, in an interview with Smithsonian magazine.

It’s exciting enough to have the opportunity to see art by some of the most important Black contemporary artists of our age—Michael Armitage, Lubaina Himid, Kerry James Marshall, Amy Sherald (a household name since painting Michelle Obama’s official portrait), Henry Taylor, Barbara Walker—but even more so when their works are collected in a thoughtful and dynamic exhibition that puts the artists in conversation with each other and with the history of Western art.

Curated by British curator and writer Ekow Eshun, The Time Is Always Now brings works by 23 African diasporic artists together in an investigation—and celebration—of how Black artists use figurative works to explore the complexities of Black life, representation, and power.

“We are in the midst of a period of extraordinary flourishing when it comes to the work of Black artists,” Eshun said at a March 6 press preview event. “These artists are being celebrated, rightly, for their ambition, for their talent, for their visual flair … but the goal of the show is not simply to recognize this …. The point is to consider what it is that they are doing within their work. What questions are being asked by these artists right now?”

To illuminate these questions, Eshun divides the works into three thematic sections: “Double Consciousness,” “The Persistence of History,” and “Our Aliveness.” The exhibition opens with a quote from James Baldwin: “There is never a time in the future in which we will work out our salvation. The challenge is in the moment, the time is always now.”

Baldwin’s call captures the sense of urgency and necessary change that unifies these disparate works. Each artist, in their own complex way, is disrupting the way Western art has historically depicted Blackness. Instead of the Black figure being sidelined to the margin, the works of these artists assert Black presence in a variety of ways.

Some directly address the absence of Black representation in Western art, like Barbara Walker’s “Vanishing Point” series, which erases white figures and highlights Black subjects in historical works, or Titus Kaphar’s “Seeing through Time,” which overlays two paintings so that historic and contemporary representations of Black figures converge and converse on a single, vibrant canvas.

Related Special Events

With a host of exhibition-related events this spring, there’s time to see The Time Is Always Now multiple times—sometimes for free. (While the museum’s collection galleries and its outdoor park are always free of charge, special exhibitions like this one require paid tickets.) Special events that allow access to the show include:

- College Night: April 4, 5–9 p.m.; free. Explore the exhibition, and enjoy art activities and dancing with a DJ. No college ID required.

- Family Studio: April 5, 10 a.m.–noon and 1–3 p.m.; free. Families can learn about poses, portraits, and people on view in the exhibit and then paint a portrait.

- NCMA After Hours: May 15; 5–9 p.m.; free.

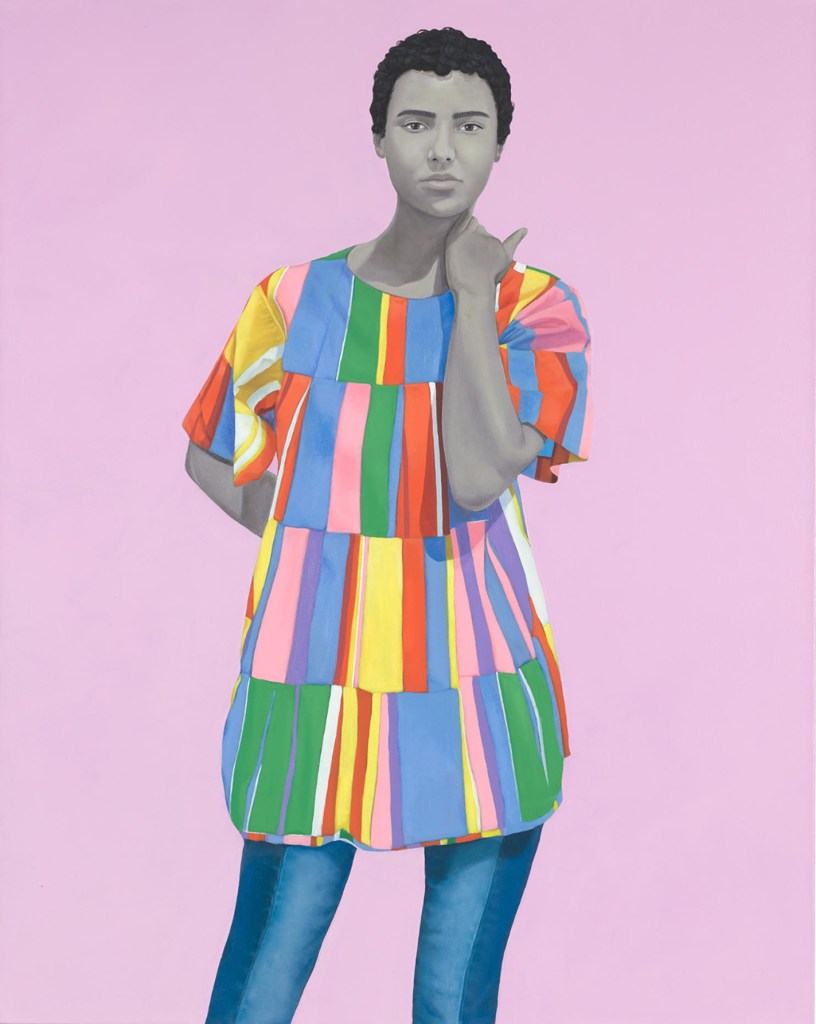

Other artists intervene in different ways, rejecting conventions such as naturalism (think of the gray skin tone of Sherald’s portraits) or using the speculative to reimage or recreate the past—and visions of the future.

“I would suggest—and the show contends—that we see a shift in perspective that takes place from that historical looking at the Black figure, which characterizes Western art history, to looking with or from the perspective of the artists or the subjects within their work,” Eshun said. “This shift is the fulcrum that this exhibition stands on.”

This shift, from looking at the Black figure to “seeing through” the eyes of Black subjects, is revolutionary. And what do we find when we “see through” the eyes of these 23 artists?

A phrase Eshun used to describe Thomas J. Price’s sculpture “As Sounds Turn to Noise” comes to mind: “an expression of multitudinousness.” Price’s piece, a nine-foot-tall bronze sculpture that depicts a young Black woman in athletic attire, Eshun explained, is not based on a single figure, but rather a composite of several people.

Price’s process of selection highlights not only the way that Black bodies have been historically categorized but also how race functions in varied ways: while it sometimes leads to marginalization and othering, it is also an expression of solidarity and an expression of an individual as part of a larger collective of Blackness. “As Sounds Turn to Noise” is a towering expression that Blackness contains multitudes.

In great contrast to the scale of Price’s work, the final room of the exhibition is almost diminutive, containing only three paintings.

The closeness of the small space reflects the intimacy of the works within. Across from each other are two paintings by Jordan Casteel, whose work often explores the relationship between artist and subject. Both are life-sized portraits—the first, “James,” from 2015, depicts a man the artist would often pass on the street as she went to work at her studio in Harlem.

Later, upon becoming friends with James and his wife, Yvonne, the couple became the subjects of the second Casteel painting, “Yvonne and James,” created in 2017. The familiarity of both portraits, with the subjects looking directly out of the canvas, seemingly locked in a gaze with the artist, makes both works feel like an intimate conversation, like both viewer and subject are in community.

the artist and Hauser & Wirth; Photo: Joseph Hyde

Similarly, the third painting in the room, a double portrait by Henry Taylor of him and fellow artist Noah Davis—whose own fantastic works are some of my favorites in the show—posits not just the possibility but the reality of Black community and Black love.

Sitting side by side in lawn chairs and rendered in Taylor’s expressive strokes, it’s a quiet moment captured with empathy. The work feels complete, the way a moment feels complete when you are with your best friend, feeling the sun on your arms, bare legs sticky against a plastic seat. Taylor’s painting radiates life, love, and also a sense of finality. (The painting’s title, “Right hand, wing man, best friend, and all the above!,” hints at the exuberance of the artist’s expression.) Perhaps the knowledge that Davis died of cancer at the age of 32 in 2015 is what gives this painting an edge of grief—he’s the one artist in the show who is no longer living.

Works like Taylor’s feel triumphant—and the whole third section of the exhibition, “Our Aliveness,” is full of such moments. Taylor’s testament to his friendship with Davis is a reminder that all the works just encountered were made by Black hands—and that the Black figure isn’t an abstract concept but a complex, lived reality.

These final three works—Taylor’s double portrait and Casteel’s “James” and “Yvonne and James”—highlight the interconnectedness of the artists to their subjects, to communities, and even to each other. The Time Is Always Now is itself a multilayered conversation between the works of artists from across the African diaspora that work individually and, thanks to Eshun’s deft curatorial skill, together to reframe the Black figure in art.

“One of the things that I think this show overall is trying to do is to think about the ways that artists, sometimes in proximity, sometimes from across different parts of the world, are thinking in concert about both the individual lived experience of Blackness,” Eshun said, “and these larger questions that come up when we consider these questions about history, about power, about marginalization, but also then about possibilities, about connection, about our shared humanness.”

There is so much to see in this visionary exhibition—so many brilliant works, full of complexity and wonder—but it is perhaps the shared dialogue between the works that most proves the show’s title: The time for reckoning, promise, and deliverance is not in the future. It is right here in the room.

To comment on this story email [email protected].