When a five-member crew of higher education professionals arrived at Saint Augustine’s University in October 2023 to scrutinize its finances and operations, the small, private, historically Black school was already on thin ice.

Founded in the late 1860s by the Episcopal Church as a school for newly freed slaves, Saint Augustine’s, also called SAU, was a pillar of the East Raleigh community with a legacy of educational access and achievement. But that reputation had become imperiled over the years as enrollment trended downward, finances dwindled, and the school repeatedly ran afoul of requirements set by its accreditor, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges, also known as SACS.

SACS had put the university on probation before, but SAU had managed to win back the accreditor’s favor—a necessity for higher education institutions to access crucial public funding.

At the 2023 meeting, two presidents of other HBCUs, two senior administrators from Christian colleges, and the vice president of SACS converged on SAU to comb through the school’s financial statements and interview more than 20 employees, trustees, and consultants.

The committee’s report, which is not public but was obtained by The Assembly and INDY, said that the school had dire and fundamental financial challenges, and a board of trustees that lacked the ability to evaluate risks to the institution.

The committee found no evidence that the board had “developed a process for managing the financials of the institution or any strategies for timely audits.” The board had consistently approved budgets since 2019 “without externally audited or verified evidence of resources or operational results.” The university’s auditors recommended “extensive training” for the board to improve its fiduciary oversight of the school.

“It was not evidenced that the Board has a clear understanding of its role in the management process, nor does it have a clear understanding or appreciation of the severity of the current fiscal issues,” the committee wrote.

Two months later, SACS withdrew the university’s accreditation, citing the board’s fiduciary oversight as one of six violations. SAU appealed the decision and clawed its way back to a probationary status with SACS, but it didn’t last. In December 2024, as the school’s enrollment dropped precipitously to just a few hundred students, SACS revoked SAU’s accreditation again.

In many ways, SAU’s plight is not that different from small colleges across the country facing enrollment declines and financial pressures—challenges that are exacerbated for HBCUs due to historical funding disparities compared with other public and private counterparts.

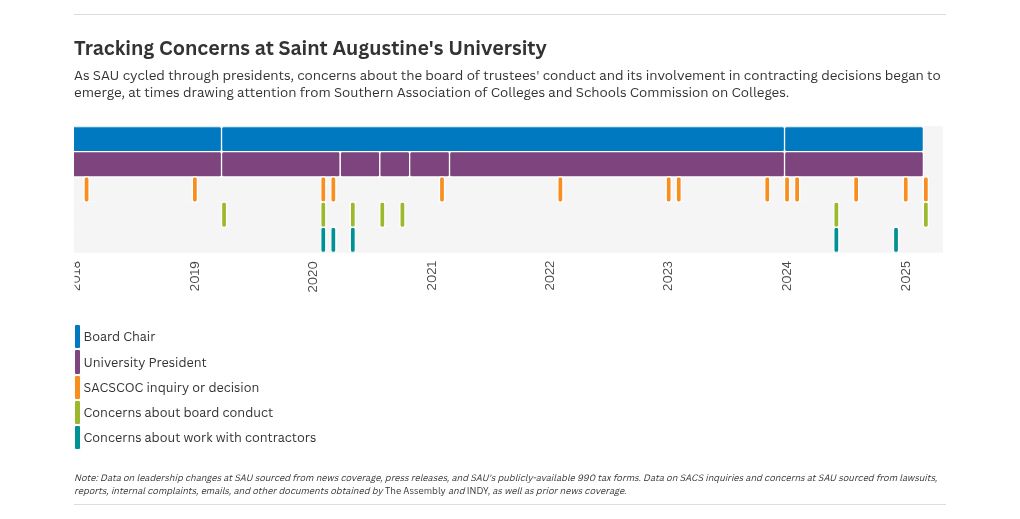

But SACS also has focused on the board charged with overseeing the university. And more than a dozen former employees and trustees have accused the board of overreach or misconduct over the past six years, according to a dozen interviews, several lawsuits, and internal complaints, emails, and documents obtained by The Assembly and INDY.

Allegations against the board, particularly its two most recent chairs, include silencing dissenting opinions, wrongful termination, and violations of university policies and SACS requirements. One alumni group, Save SAU, sued the school in hopes of reconstituting the board. The state attorney general’s office is also investigating the school over allegations involving the board of trustees, a spokesperson for the attorney general said.

“Having survived so much for so long, SAU now teeters on the edge of chaos, brought to its knees by the misfeasance, malfeasance, and utter neglect of its Board of Trustees, and especially its two most recent chairmen,” reads the Save SAU lawsuit filed against the school in May 2024. (It was dismissed in November for lack of standing.)

The university denied all allegations of wrongdoing on behalf of Brian Boulware, the current board chair, and James Perry, the immediate past chair who continues to serve as a trustee.

“Chairman Boulware, Trustee Perry, and the Board of Trustees have demonstrated their commitment to addressing such baseless claims while steadfastly working closely with the university’s administration to execute a robust financial plan to position SAU for future success,” the university wrote in a statement. “We remain dedicated to our mission and the well-being of the university amidst all opposition.” Perry didn’t respond to specific requests for comment.

Boulware said in an interview that the university’s financial predicament long predated the actions of the current board. “Years of neglect from within have caused the problem,” Boulware said. In response to SACS’s citations of the board in recent years, he said that trustees have made changes, including hiring an internal auditor and taking steps to get financial reporting processes in order. SAU has been negotiating a deal to lease an undisclosed amount of its property to a Florida-based developer, which has been controversial with alumni and onlookers but which university officials say will give them more financial runway.

Boulware said he would not resign now, as some alumni have demanded, saying that would have a “devastating” and destabilizing impact on SAU while its future remains uncertain. Once the university is on a path to long-term success, he said he’d consider stepping down.

I’m not a quitter, we’re going to fight this through. … Once we prevail, I’ll be glad, on my terms, to yield to new leadership.”

brian Boulware, board chair

SAU will appeal SACS’ decision to pull its accreditation at a hearing on Thursday. But even if the university retains its accreditation, its long-term survival remains an open question.

Trustee Trouble

A little over six years ago, the mood on SAU’s campus was much lighter.

“By God’s grace, I am here today and can report to you that we have saved Saint Augustine’s University,” Everett Ward, the university’s president, declared in December 2018 to the cheers of students, alumni, and community members packed into the library. The university had just come off probation with SACS after struggling for three years.

Ward joined SAU after his predecessor was fired in 2014, amid financial turmoil at the university, and pressure was on him to turn the situation around. Ward was a former executive director of the North Carolina Democratic Party and a graduate of the school. Under his leadership, annual donations nearly tripled over a four-year period, the school said. After a yearslong streak of declining enrollment, headcount had also begun to tick up.

“Now that we have no issues with accreditation,” Ward told the crowd in 2018, “the sky’s the limit.”

But the celebration would be short-lived. While some trustees at the time saw the SACS decision as a victory for Ward, other members worried the university was not out of the woods and questioned whether he was leading the institution in the right direction.

Ward announced in January 2019 that he would retire that summer, but that wasn’t quick enough for some trustees. In March, the university announced that Ward’s replacement, interim president Gaddis Faulcon, would begin “effective immediately.”

Perry, a retired Florida Supreme Court justice who was chair of the board in early 2019, told WRAL that the school could not “have two presidents.”

Ward did not respond to requests for comment, but four former trustees said Perry and Boulware, an alumnus and businessman, were among his critics. The pair “facilitated Ward’s departure,” said Rudolph Morton, who was then vice chair of the board. “It definitely shifted the power of the university to Boulware and Perry,” Morton said.

Charles Francis, a Raleigh attorney who had served as general counsel at SAU since 1994, quit the day Faulcon was announced as interim president, writing to the trustees that pushing out Ward might have violated SACS rules by broaching the firewall between the responsibilities of the board and administrators.

Ward’s exit was followed by years of turmoil for the board. By the end of Perry’s first year as chair, 15 out of 21 trustees had left the board, according to the school’s public tax forms. Multiple trustees told The Assembly and INDY that they were given less and less information on the university’s finances, and they said decisions were frequently made without following university bylaws and procedures.

It rapidly became “the most dysfunctional board that I had ever served on,” said Henry Debnam, a former trustee who resigned. “And I have served on quite a few.”

Having survived so much for so long, SAU now teeters on the edge of chaos, brought to its knees by the misfeasance, malfeasance, and utter neglect of its Board of Trustees, and especially its two most recent chairmen.

save sau lawsuit

One former trustee submitted a complaint to SACS claiming Perry “stacked the [board] members to his favor,” including by removing several trustees with ties to the Episcopal Church, which is still a financial backer of the school. Anne Hodges-Copple, an Episcopal trustee who was among those voted off the board, said in an interview that “it was very clear I was targeted for questioning decisions” Perry and Boulware had made. (Perry and Boulware did not respond to specific questions about removing trustees.)

Some trustees left of their own accord. They included John Larkins, who came to the board in 2019 as an “alumni trustee” nominated by SAU’s National Alumni Association. He resigned less than a year later and led the association in a vote of no-confidence against the remaining trustees, calling for the board to be reconstituted.

Larkins and Debnam later joined the 2024 alumni lawsuit that sought to replace SAU’s board. The lawsuit stated that instead of resigning, the trustees revised their bylaws to limit the association’s power to select an alumni trustee and make it harder to remove trustees—requiring a two-thirds majority rather than a simple majority.

“By driving away board members who might ask hard questions or look underneath all the rocks, the Board of Trustees is now a corrupt echo chamber,” the lawsuit said.

In response to questions, the university directed reporters to a June 2024 letter from Boulware to the SAU community in which he called the complaint “defamatory” and said Larkins and Debnam were “disgruntled former board members” making “unsubstantiated claims” as part of a “personal political agenda.”

Boulware wrote that the former trustees’ “tactics are irresponsible, unconscionable, and equivalent to a terrorist attack against SAU.”

The disputes stretched beyond the board, as well.

George Williams, a 1965 graduate, coached SAU’s track and field teams to 39 NCAA Division II national titles over four decades, served as the athletic director for 23 years, and also coached the U.S. Olympic track and field team in 2004. He is a three-time recipient of the Order of the Long Leaf Pine award, the highest civilian honor in North Carolina.

In December 2019, Williams wrote to a long-time trustee complaining about Boulware’s behavior toward SAU employees, without giving examples. Williams urged the board to formally censure Boulware.

“In my 43 years as a senior staff member … I have never seen our employees suffer the level of unnecessary harassment that Mr. Boulware has inflicted,” Williams wrote. “No one should have to endure the verbal abuse, threats and physical intimidation that he shows employees.”

Eight months later, Williams was out of a job. The university released a statement saying it offered to keep Williams as track coach but replace him as athletic director, and he declined the offer. Williams filed a wrongful termination lawsuit accusing the university of not investigating his complaint about Boulware, which he included in the legal filings. He said he was told in July 2020 to accept a 50 percent pay cut and step down as athletic director or be terminated, which he believed was retaliation.

Faulcon, who had been named interim president in 2019, joined Williams’s lawsuit, saying he was ousted for refusing to participate in Williams’s termination. Three other former SAU employees also signed on, saying they were fired for raising complaints about the trustees or other issues at the school.

Boulware and Perry didn’t respond to questions about the leadership changes. In their responses to the 2020 lawsuit from the former employees, they denied all allegations of misconduct and retaliation.

The lawsuit was voluntarily dismissed in April 2021. The lawyer who represented Williams and the other plaintiffs said he could not comment about the case, including how it was resolved. Williams declined to comment, and the other plaintiffs didn’t respond to requests for an interview.

Construction of Reality

Multiple employees wrote internal complaints about Boulware’s handling of construction contracts at the university, according to documents reviewed by The Assembly and INDY. The complaints concerned his relationship with the Hughes Company, a Georgia contractor that worked with Boulware on a cigar bar he opened in the Atlanta suburbs.

Ronald Brown, a longtime university administrator, wrote in an internal complaint that Boulware hired an Atlanta company in 2019 to renovate dorms that Brown said had HVAC, mold, and mechanical issues. He said Boulware was continually involved in “oversight” of their work as a “construction facilitator,” but he didn’t think the contractor had resolved the problems. (Brown, who joined Williams’ 2020 wrongful termination lawsuit, did not respond to requests for comment.)

After Brown’s complaint was published in HBCU Digest, an industry newsletter, SACS’s vice president asked the university to prepare a report addressing the allegations, documents show.

Debra Clark Jones, who was vice president of university advancement and external affairs at the time, was tasked with producing the report. By the end of her efforts, she filed her own internal complaint against the board of trustees, which was also later reported by HBCU Digest.

“My moral dilemma reached a breaking point,” Clark Jones wrote.

Clark Jones wrote that the university had paid the Hughes Company $375,000 in 2019 to repair dorm buildings without conducting a bidding process, signing a contract, or receiving board approval for the project. (Four former trustees who spoke with The Assembly and INDY said they did not recall voting on or approving work the Hughes Company performed in that period.)

As questions about the contractor arose, Clark Jones wrote that during a call with Boulware and Maria Lumpkin, the university’s interim president at the time, Perry suggested that they “amend” board meeting minutes to indicate a contract was approved. Clark Jones said they ultimately didn’t submit the inaccurate minutes to SACS, but she worried the officials could put the school’s accreditation at risk.

“This behavior places policies and processes secondary to how they choose to manage issues facing the institution,” she wrote, adding that it is clear that Boulware and Perry “love the institution and have had genuine concerns about its dire state.” Still, she continued, “their concerns, shared by many, do not justify committing fraudulent acts.”

Perry and Boulware did not respond to specific questions about the complaint. The university denied any wrongdoing on their behalf. Lumpkin and Hughes Company representatives did not respond to requests for comment.

In the letter Boulware wrote last summer, he said that he brought the Hughes Company to SAU upon learning that the university had “less than $40,000 in the bank,” while nearly $2 million in dorm renovations were needed. Boulware wrote that the Hughes Company agreed to fix the dorms “at cost” and that “all parties, including former [board] members and complainants, understood and agreed with the solution.”

A lawyer for SAU raised concerns in early 2020 about a second project Hughes worked on, updating a community health center under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education. “There appears to be a contractor performing work on a building without a contract, who did not bid for the work, who may not be licensed in North Carolina,” the lawyer wrote, noting that could violate federal or state rules. Federally funded projects often must conduct a competitive bidding process.

Lumpkin responded that a Triangle-based company licensed in North Carolina was the general contractor. She emailed the lawyer a copy of the contract, though she said it wasn’t “executed yet.”

Derrick Sauls, then chair of the university’s department of public health and the project manager for the health center renovation, questioned why the Hughes Company was involved. “Nobody ever explained why we needed somebody from Atlanta,” Sauls said.

This behavior places policies and processes secondary to how they choose to manage issues facing the institution.

Debra clark jones, former university administrator

The university’s last four audits, which are public documents, found that “significant contracts” were not appropriately approved prior to execution, and the university did not adhere to “appropriate procurement policies and procedures,” including for projects with federal funding. The university responded that it checks for conflicts of interest among board members and university employees.

In an interview, Boulware said connecting Hughes Company to SAU for the dorm renovations was part of his role and obligation as a trustee. “A board member is supposed to bring resources to the university,” he said. Boulware also said he was not involved in hiring Hughes for the health center project.

Boulware’s personal relationship with Hughes and with another trustee who invested in his cigar bar business did not end on such a positive note.

A court ordered Boulware to pay the Hughes Company $94,000 that he owed them, and fellow trustee George Brooks sued Boulware to recoup a $600,000 loan. (Boulware disputes the ruling in Brooks’ favor and is asking for a new trial, according to court filings.)

Walking in a Graveyard

By the time SACS revoked the university’s accreditation in December, alumni, former employees, and former trustees were openly criticizing university leaders.

In recent years, SAU had dealt with IRS tax liens totaling $10 million, a series of lawsuits claiming it failed to make payments to numerous contractors totaling more than $1 million, and a U.S. Department of Labor investigation that ultimately awarded nearly $1 million in unpaid wages to more than 370 employees, a department official said. Recently, deferred maintenance issues on campus forced the school to move all classes online. Before SAU was put on probation, the accreditation agency initiated four monitoring reports into the school between 2020 and 2023, SACS’s website shows.

A series of recent decisions have intensified the public outcry. The university drew hefty criticism for taking out a loan last fall with a 26 percent interest rate. SAU rejected a lower-interest loan offer with the stipulation that Boulware and Perry resign, INDY reported.

Now, a land lease deal under negotiation behind closed doors with a Florida developer leaves the future of SAU’s campus property, its most valuable asset, up in the air.

For Benjamin Johnson, an alumnus and member of the group that sued last year, the question of the school’s survival is deeply personal. Johnson’s father taught science and coached football there for 35 years, and his mother, three brothers, and more than 20 cousins, nieces, and nephews attended. He described matriculating there himself as a true homecoming.

Decades removed from those warm memories, he’s convinced of who’s to blame for the university’s downward spiral. “The one constant denominator through all of this has been the board,” Johnson said.

Felecia Commodore, an associate professor of education policy at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who studies HBCUs and board governance, said universities facing existential challenges often have to take a critical look at their oversight bodies.

“Externally, if it [the board] signals that instability and problematic operation and possibly fiscal concerns, it makes it hard to attract partners,” Commodore said. “This is not the time that we want to be restricting resources.”

For the contingent that wants the board out, there are no avenues beyond public pressure and lawsuits. Although the state attorney general’s office confirmed that it is investigating allegations against the board of trustees, it’s unclear how long that will take or what authority the office can exercise.

At this crucial junction, Boulware said it would be “irresponsible” for the board to step down. “I’m not a quitter, we’re going to fight this through,” Boulware said in an interview. “Once we prevail, I’ll be glad, on my terms, to yield to new leadership.”

University officials have argued that it is actually their critics who have caused the most harm to the institution’s reputation. Boulware previously described SACS’ accreditation decisions as the result of “a premature investigation fueled by personal vendettas rather than factual evidence.”

Janea Johnson, a spokesperson for SACS, said that if the agency receives information that raises questions about a school’s compliance, it follows a standard procedure to determine compliance and provides multiple opportunities to demonstrate improvement. “Being removed from membership is definitely a rarity, so I would hesitate to say that it is vindictive or retaliatory when there are so few instances,” Johnson said.

Alumni and university leaders are both focused on keeping the faith as the university heads into its accreditation appeal hearing.

The university will need to demonstrate that it can operate sustainably with sound financial resources and that it can comply with state and federal regulations. It will also need to show that its board of trustees is capable of overseeing its finances.

Even if the university is successful in convincing SACS, it could still be too little, too late.

Steven Williams, a 1998 SAU graduate and the founder of the alumni group Falcons Unite, said circumstances have never felt more dire. Alumni aren’t donating like they used to because “it’s like giving to a black hole,” he said. Nor does campus feel like it did when he was a student.

Walking around SAU today, Williams said, is “like walking in a graveyard.”

Support independent local journalism. Join the INDY Press Club to help us keep fearless watchdog reporting and essential arts and culture coverage viable in the Triangle.

Chloe Courtney Bohl is a corps member for Report for America. Reach her at [email protected].

Erin Gretzinger is a higher education reporter at The Assembly. She was previously a reporting fellow at The Chronicle of Higher Education and is a graduate of the University of Wisconsin at Madison. You can reach her at [email protected].

Comment on this story at [email protected].