Yevonne Brannon remembers taking her toddler daughter to the grand opening of Athens Drive Community Library, housed inside Athens Drive Magnet High School, in 1978. This was before the trails at Lake Johnson Park were built out, long before the opening of the Thomas G. Crowder Woodland Center.

Brannon’s grandson just graduated from Athens Drive High, marking a full-circle moment for the family—the kind of moment that families living in Athens Woods, Bryn Mawr, and all around Lake Johnson want to continue enjoying for decades to come.

“I’m just one of many who’ve lived in the neighborhood forever and have worked really hard to keep the amenities,” says the West Raleigh resident, longtime community activist, and former Wake County commissioner.

Whether they can, residents say, hinges on whether a new version of the library, slated to open sometime in the next seven years, will remain in the community. Due to long-running safety concerns and a renovation of the high school planned next year, a replacement for Athens Drive Community Library was part of the county’s $142 million libraries bond package that voters approved in November.

But residents—already distressed over three prior attempts to close the library, its starkly reduced hours, and limited resources compared to other Wake libraries—are worried about the county’s commitment to keeping their treasured library close by. Public records show county staff have already considered a site in Cary, nearly three miles away.

“We want it to be a safe place for our kids, something they can walk to,” says Hannah Mckenzie, who lives on Athens Drive and is a member of the Friends of Athens Drive Community Library advocacy group that Brannon chairs. “We want the folks in the community who don’t have access to personal vehicles to be able to access the library.”

The communities surrounding Athens Drive Community Library are some of the densest and fastest-growing in Raleigh. They’re close to NC State University’s campus, the State Farmers Market, and the Beltline, though the next closest libraries—Oberlin Regional and Cary Regional—are four and six miles away, respectively. The neighborhoods around Athens Drive are also some of the city’s most culturally diverse and economically mixed communities. Patrons walk, bike, push strollers, and pull wagons to the library regularly. It’s located along a GoRaleigh bus line.

“That’s what makes this library unique—we’re hitting big swathes of this really diverse population,” Mckenzie says. “That’s what we would like to see again, and we’re not seeing it now with the library only being open half-time. If they put the library here, we’ll be able to see that vibrancy again.”

A library in limbo

At an evening community meeting at the end of January, dozens of residents crowd into a reading corner at the library to discuss with county staff plans for its replacement. The Friends of Athens Drive Community Library give a presentation and community members chime in with their stories.

A young mom, newly relocated to Raleigh from Michigan, tells the group she walked over to the library with her daughter for story time, met new neighbors, and made friends. A mother with an adult son with special needs says the pair visits the library frequently. Once, her car broke down in the library’s parking lot, a situation that normally would cause her son stress. Instead, she says, they were able to walk home because they live so close by.

The library opened in Athens Drive High School in the 1970s thanks largely to the efforts of Raleigh City Council member Miriam Block.

“She was what you’d call a fiscal conservative,” says Brannon. “She made big arguments that we shouldn’t be building all these different school buildings and county facilities and that taxpayers should be sharing resources. So she made a good case for ‘We need a library, we’re building the school—we should put the library in the school.’”

That unorthodox cohabitating arrangement hasn’t always been easy for the high school and the community library. Security concerns about having members of the public inside the high school have meant that county officials glanced in the library’s direction periodically when they wanted to pare down the budget. The community has successfully rallied to save the library from closing three times in the last 15 years, in 2009, 2015, and 2021. That last time, in 2021, the library’s service hours were reduced to 35 hours a week. Other libraries in the county’s system are open for 61 hours.

“Every time we get a new principal [at the high school], the rules change, the principal’s comfort level with the public in the building changes,” says Mckenzie.

During a community meeting in June 2022, residents thought they had come to an agreement with county staff that the library would be rebuilt as a freestanding building on the high school’s campus. The high school had plans to renovate soon, anyway, and last year, replacement of the Athens Drive Community Library was part of the successful countywide library bond. It was one of two “replacement library” projects requiring construction of a new facility (Wendell is the other), and one of five new libraries planned for with a dedicated sum of $67.1 million.

The residents make a good case for keeping the library in their community. Data the Friends group compiled shows that 11,500 people live within a 30-minute walking radius of the library at its current location. The median household income for those residents is $65,400, and 45.7 percent of the residents are nonwhite. In the census tracts that overlap with the 30-minute walkshed, 6.3 percent of households are carless and 48.7 percent of households own one vehicle.

Digging in even more, the EPA rates the census tracts around the library as highly walkable, with a high population of residents who have access to public transit.

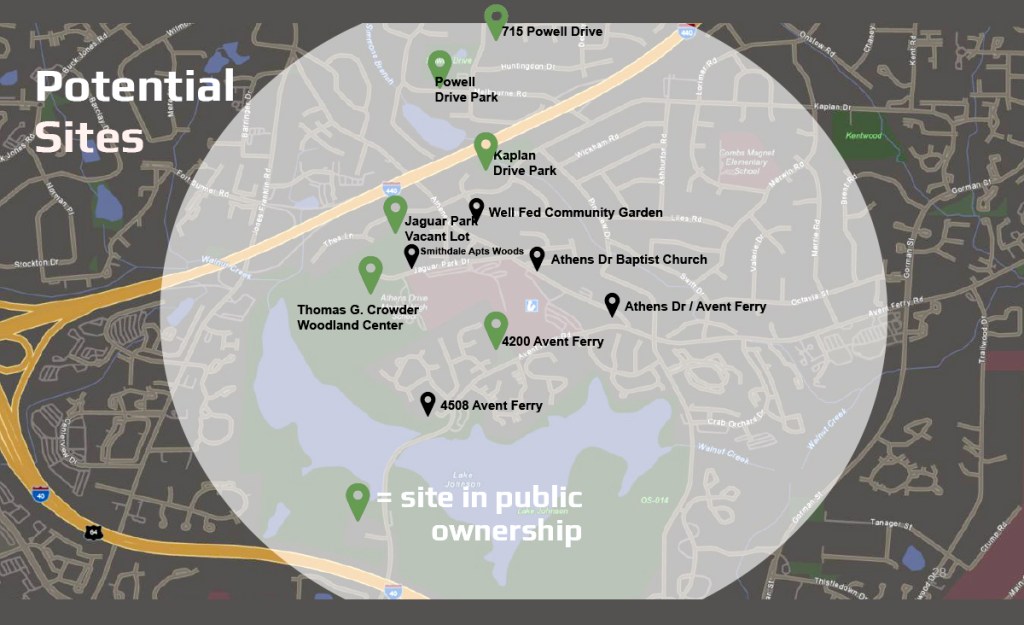

And there is nearby land available, the library advocates point out. There’s the massive Athens Drive campus, of which a replacement library could take up a small portion, sharing parking with the school. There’s also a forested parcel at 4200 Avent Ferry Road that the City of Raleigh owns, as well as several city-owned lots at the end of Jaguar Park Drive. And, residents say, they’ve suggested several potential sites to county staff: privately owned lots along Avent Ferry Road, Athens Drive, Kaplan Drive, and Gorman Street, all plots near the high school that are currently underutilized and that have owners who may be interested in selling.

A community library doesn’t need a ton of space, the residents argue. The median footprint of Wake County’s 23 libraries is 2.63 acres, and most of the community libraries (and one regional library—Cary’s) sit on less than three.

“If we’re being asked to suck up all this density,” says Brannon, “don’t we deserve a library we can walk and bike and ride the bus to?”

“We keep fighting”

Wake County’s official line is that it is in the beginning stages of the land acquisition process and working with its real estate team to start looking at properties. The county’s Facilities Design and Construction Department will submit a request for qualifications for design firms to get involved with all of the library bond projects once land parcels are identified.

The projected size for the replacement library is 12,000 square feet; the county wants four to five acres for parking and other amenities, though county officials say they would be open to smaller acreage depending on partnerships and the shape and topography of the proposed site. And the county lays out a preferred search area for a new site for the library that fans a 2.5-mile radius around Athens Drive High School.

“That’s the preferred area for the county for the library as well [as the community’s],” says Tammy Baggett, director of Wake County Public Libraries since June.

But there are two more tiers of search area radiating out from the preferred area, and the county’s goal with all of its library bond projects is to increase the number of Wake residents with access to a library within a 10-minute drive from their home. That could put the Athens Drive replacement library outside of Raleigh city limits.

It’s also not clear whether the Athens Drive High School campus is still under consideration as a site for the replacement.

“It was decided we were not going to look at putting the library on the WCPSS property,” wrote Elizabeth Sharpe, senior director of facilities design and construction for Wake County Public Schools, in an October 2023 email to Mark Roe, the county’s former senior facilities project manager who has since retired. “The property is very tight and having a public library on a school site poses security concerns.”

Sharpe added that the CORE team, a joint team comprised of staff from WCPSS and Wake County tasked with guiding long-range planning decisions for the Capital Improvement Plan, “made the call to find another location for the public library.”

Other records show county staff has already considered a site as far away as Cary.

In January 2024, Frank Cope, Wake County’s community services director, sent a screenshot of “a possible site for the Athens Drive replacement library” on “property owned by WCPSS at the corner of Tryon and Yates Mill Pond Road” to deputy county manager Ashley Jacobs.

“It is 7 minutes (3 miles) from the existing location,” Cope wrote. “We will also be looking for other locations, but this is certainly a viable location.”

Other locations could potentially include city-owned property, including a city-owned lot located behind the high school, and the City of Raleigh has made it clear that it’s a willing partner in helping to keep the library in the community. In a February 4 letter to the board of commissioners and county manager, District D city council member Jane Harrison advocated for a city-county partnership on the replacement library.

“We’re thrilled for the opportunity to build a new Athens Drive Community Library,” Harrison wrote, noting the area’s rapid growth, racial and economic diversity, pedestrian and bus access, and 15-minute frequent service.

“We ask for your commitment that it stays in the current neighborhood,” Harrison continued. “We expect further population density in this area due to the City’s missing middle housing policies. We emphasize the need for the Athens Drive Library to remain in Raleigh and be accessible to our residents.”

Harrison said Raleigh’s city manager has also worked to identify opportunities for city-owned properties for the replacement of the library. All six other council members and the mayor signed the letter.

City-of-Raleigh-partnership-on-libraries

The county does look to be exploring a partnership with the city.

“Perhaps the next best step is for you and I to discuss what we are looking for to see if any of the property owned by Raleigh is an option,” wrote Cope, the community service director, in an email to Ralph Recchie, Raleigh’s real estate manager, on June 3.

Jacobs, the deputy county manager, told the INDY that the county is evaluating “every potential property for the project” and that county staff are “very receptive to hearing ideas and suggestions from the community.”

“We want to build a library that will serve the community’s needs,” she wrote in an email.

Still, residents say they aren’t clear who at the county is moving the replacement library project forward and whether the different governing bodies—particularly the county and the school system—are having productive discussions with one another.

Baggett says she thinks partnerships are definitely on the table, though she says she has not been “personally involved in any of those conversations.”

But she wants the community to know that county officials are listening; ultimately they will make a recommendation on the location to the county’s board of commissioners, who will vote on whether to approve the site.

“No decisions have been made and we are really trying to understand the need, the interest,” she says. “We appreciate them advocating for their library and taking all those things into consideration when planning really does get underway for these next steps.”

The library’s advocates are frustrated but insistent; this isn’t new territory for them.

“The criteria [for what’s needed for the replacement library] keep changing,” says Brannon. “So we keep fighting to save our library. This is a great example of the conflict of density and growth and amenities, but when there’s a will, there’s a way.”

Follow Raleigh Editor Jane Porter on X or send an email to [email protected].