At 9:15 a.m. on a cold, rainy Tuesday, Todd Stiefel parades up Raleigh’s Fayetteville Street in a judge’s robe and powdered wig.

The 50-year-old millionaire, with an “I AM NOT ELECTION-GRIFTIN’ JUDGE GRIFFIN” sign around his neck, is staging a one-man protest against Republican candidate Jefferson Griffin’s attempt to throw out 60,000 votes in the North Carolina Supreme Court election.

“I’m actually a little surprised there’s no one else here,” Stiefel says, gesturing around the outside of the state supreme court building with a gavel. “I assumed other people would be protesting.”

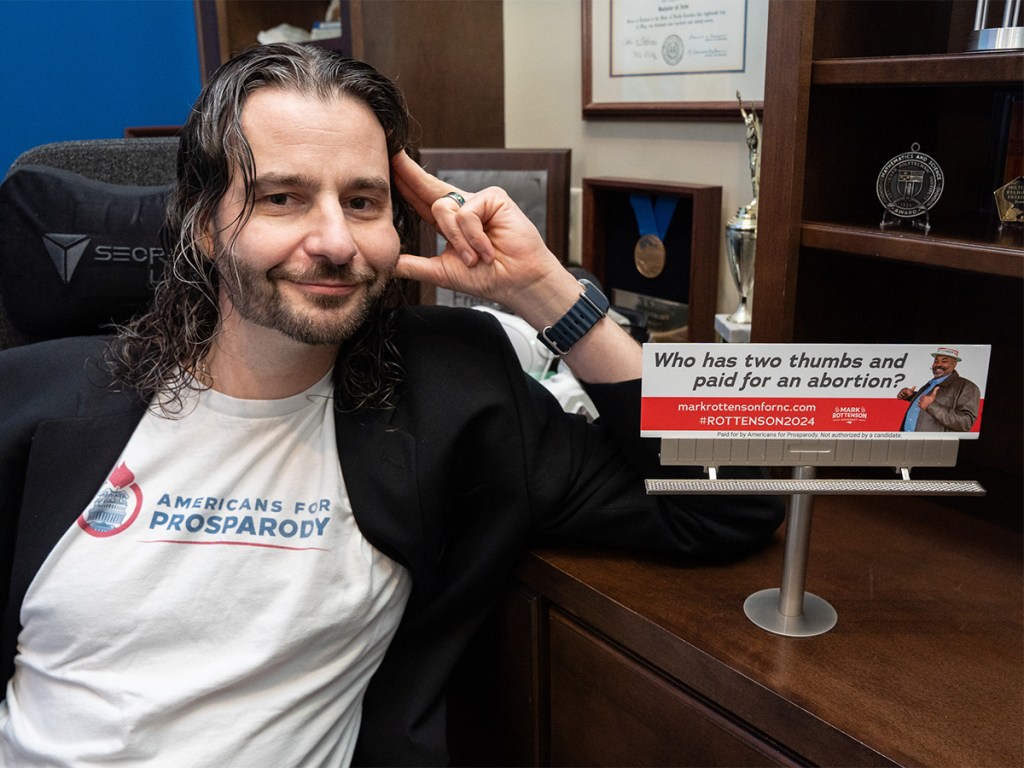

Dressing up like a judge—and hiring a digital mobile billboard to cruise around the block with a photoshopped image of five Republican justices roasting marshmallows over burning boxes of ballots—is Stiefel’s most recent, but probably not most bizarre, political stunt.

In recent years, Stiefel has hired a plane to fly a banner over an antimasking protest and partnered with a comedy team to ambush state superintendent candidate Michele Morrow with printouts of her old tweets calling for Barack Obama to be executed. In the run-up to the 2024 election, then-gubernatorial candidate Mark Robinson called Stiefel “bound and determined to destroy me” after Stiefel set an AI-generated version of Robinson loose on the airwaves with a $1 million ad buy.

His full-time job of ridiculing North Carolina’s most ridiculous candidates is, so far, self-funded. Stiefel is the benefactor of his own political action committee (PAC), Americans for Prosparody.

His family owned Stiefel Laboratories, the world’s largest private manufacturer of dermatology products in the 2000s. With a Duke education and 14 years at the family company, he was groomed to take over, until the family decided to sell the company to pharma and biotech giant GSK in 2009.

“I went from knowing my career and having that long-term future planned [to], all of a sudden, unemployed,” he says.

Unlike most suddenly unemployed people, though, Stiefel was also rich. Not, like, Koch brothers rich, but rich enough that he wasn’t scrambling to send his résumé to recruiters. Following suggestions to find a cause he was passionate about, he dove into activism.

“I just went in full blast and immediately took it as a full-time job,” Stiefel says. “It was important to me to show my kids that work was important.”

For a decade, Stiefel has been especially focused on organizing and advocating for atheists. That work morphed into an education campaign against Christian nationalism, which found a perfect target in Robinson and his especially violent brand of political rhetoric.

Comedic relief

Stiefel spent his 2024 election night celebrating Robinson’s defeat alongside Democratic bigwigs at the party’s Raleigh gathering. He donated at least $40,000 to Democratic candidates and PACs in 2024 alone and at least $18,000 to now-governor Josh Stein since 2016 (for one 2023 donation, Stiefel listed his occupation as “provocateur”). But his allegiance, he says, isn’t to a particular party.

Stiefel was raised on capitalism and Catholicism in Miami.

His grandfather Werner, inspired by the capitalist utopia described in Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged, tried to start his own tax-free micronation on an artificial Caribbean island. He eventually gave up his “Operation Atlantis,” but a young Stiefel would still receive cash in the form of decas, issued from the Bank of Atlantis, for Christmases and birthdays.

Stiefel says his family wasn’t strongly religious, but like many he went to college and started questioning the logic behind the faith. A Republican for his early adult life, he was surprised by what he saw as an outright disrespect toward atheists and an overall lack of compassion.

“I left the Republican party over gay rights,” Stiefel says. After the January 6 riots he briefly registered as a Democrat when he saw how Republicans failed to rebuke Trump. “And then I left the [Democratic] Party because, oh my gosh, it was so crazy liberal, I couldn’t do it. And it was so damn dysfunctional.”

So in 2024, he started work on Americans for Prosparody, a play on the billionaire Koch brothers’ conservative Americans for Prosperity, hoping that comedy could cut through the traditional media din of an election.

“The vision is to essentially create a sustainable dark-money group that can use comedy to educate on American corruption, extremism, and authoritarianism,” he says. “I think, like a lot of Americans, I was feeling angry at how broken the system is. And powerless about how little I could do about it, even with money. And this was the only way I could figure out to really make a difference and to be happy and to laugh while doing it.”

“Maybe If I were a billionaire”

Andrew Carnegie argued that wealth should be put to use to produce the greatest benefit for society. It’s not yet clear whether Americans for Prosparody is an effective tool for producing that benefit or if it’s just a pet project that no one close to Stiefel is willing to advise against.

Robinson ultimately lost his election for governor by 15 points after CNN reported that he had posted about being a “Black NAZI,” among other things, on a porn website starting in 2008. With all that going on, it would be difficult to credit Stiefel with destroying Robinson, but Stiefel believes the PAC “might have” played a role in taking down Morrow, who only lost by about 2 percent.

His approach relies on the idea—and Stiefel seems to believe it—that people are still persuadable. Perhaps that comes from his grandfather’s Randian influence. “When I disagree with a rational man,” writes Rand, “I let reality be the final arbiter: If I am right, he will learn; if I am wrong, I will; one of us will win, but both will profit.”

“The vision is to essentially create a sustainable dark-money group that can use comedy to educate on American corruption, extremism, and authoritarianism… This was the only way I could figure out to really make a difference and to be happy and to laugh while doing it.”

Todd stiefel

Chris Cooper, professor of political science at Western Carolina University and a man quoted in every high-quality story about North Carolina politics such as this one, isn’t so sure about the impact, yet. Is Stiefel just pissing his money into a political void?

“If the goal is to move the needle on a few targeted general assembly seats and the messages are tailored to that goal, then it’s as good a use of money as most other political expenditures,” Cooper says in an email. “If the goal is to discredit the image of the Republican Party in general, then it’s pissing money away. And, I might add, pissing it into a void the size of the Pacific Ocean.”

John Galt, the Übermensch of Atlas Shrugged, reshapes the world through sheer force of will and conviction of purpose. Stiefel isn’t convinced he can bring about a political sea change with a few million dollars (last year nearly $16 billion was spent on federal elections).

“I can’t change the arc of history,” he says. “Maybe if I were a billionaire. I have only the ability to nudge the needle a little bit.”

Voters are seeing his work, whether it sways them or not. The video of Morrow got nearly 9 million views on Twitter. On Facebook, ads featuring an AI-generated Robinson voice garnered thousands of likes and shares—though many comments praised Robinson.

“Love this man, GOD BE WITH HIM,” commented one Cheryl Sawyer on an ad featuring Robinson holding a severed head. “He has my vote!” agreed dozens of other commenters.

Zack Czajkowski, a Durham-based Democratic operative, is the political consultant for Stiefel’s fledgling PAC and his number two on the project. He says the campaign doesn’t need to reach all 11 million North Carolinians to be effective.

“If we can get 10,000 people in North Carolina to say ‘that’s funny’ and think a little bit harder, and then 10 percent of those—you move 1,000 votes,” Czajkowski says. “Do you know how valuable moving 1,000 votes is in an election that could be decided by 10,000?”

Czajkowski, who worked on the Obama and Hillary Clinton campaigns, says he initially hesitated to publicly affiliate himself with something as out of the box as Americans for Prosparody. And while he doesn’t like calling it “weird,” that’s ultimately why he’s sticking with it.

“It might not work. I hope it goes swimmingly and that we completely change the playbook. But if it doesn’t work, we tried,” he says, adding that billions are already being spent “on the traditional playbook.”

A Wild Experiment

Stiefel’s rogues’ gallery is as eclectic as his work. Robinson and Morrow headline a list that includes former Stiefel Laboratories employees as well as major nonprofits.

In 2020, Stiefel Laboratories and Charles Stiefel, Todd’s father, paid a $37 million settlement to shareholders who claimed the company “failed to disclose negotiations … that ultimately resulted in [GSK] purchasing Stiefel Laboratories for a share price more than four times higher than the share price the company paid to employee shareholders,” per the Securities and Exchange Commission. Todd Stiefel, who wasn’t named in the suit, says his father ran the company with “absolute integrity.”

Stiefel’s atheism has been a point of contention with several nonprofits hesitant to accept his sizable donations (“I cannot begin to tell you how demoralizing it is,” he says).

As an example, in 2010, Stiefel donated $20,000 to the ACLU of Mississippi to help sponsor a prom after a lesbian couple was barred from attending theirs. The organization rejected the gift, concerned about the perception of Mississippians who “tremble in terror at the word ‘atheist.’” The national ACLU eventually stepped in, and with Stiefel’s donation and support from celebrities rallied by the controversy, the event went forward.

“I went to the prom, and Questlove performed,” says Stiefel. “It was cool.”

Stein’s campaign team was careful to keep Stiefel at arm’s length, too. When the first anti-Robinson ads came out, Stein told WRAL that “any use of AI to mislead voters is unequivocally wrong and has no place in this campaign.”

Czajkowski called the Stein reaction a “bummer” but added that he understood why the campaign was cautious about associating with ads that depicted Robinson yelling at Martin Luther King Jr. and boasting about paying for an abortion wearing a devil onesie.

Czajkowski is unlikely to say something bad about his boss. But he seems to genuinely admire Stiefel’s dedication.

“Most [rich people] just buy another car, buy another house, start a charitable trust just for write-offs,” he says. “Here’s a guy who gives a shit. Maybe you agree with him, maybe you like what he’s doing, maybe you don’t. But you just can’t argue with the fact that the guy cares, that he’s trying.”

Why doesn’t Stiefel just write some checks and spend his days at the beach rather than running around rainy Raleigh in an itchy wig?

Maybe that, too, could be answered by Rand, who wrote, “Your work … That’s the meaning of life.”

Stiefel says that the often-complicated experience of working with nonprofits pushed him to try projects that he has more control over. He also admits “a high bias” for his own ideas, like the “wild experiment” of launching his own comedy PAC.

Cooper says Americans for Prosparody is “more a twist on what already exists than a new approach to campaigning,” citing Stephen Colbert’s Americans for a Better Tomorrow, Tomorrow PAC and FireMadison, a PAC created to troll and destroy former NC congressman Madison Cawthorn.

“In a way, it’s very common,” says Cooper. “As [Americans for Prosparody] points out, wealthy people creating and running super PACs to influence election outcomes is common in America—so common that the best way Stiefel has to combat wealthy people creating super PACs is to mock wealthy people using super PACs by … well … using his considerable wealth to create a super PAC.”

If the PAC is an experiment, it’s too soon to determine its success. Stiefel and Czajkowski hinted at a larger launch for their next project, EvilPAC, in the spring. The satire campaign already has a website with teasers like “Do you have Fuck You Money? Are you growing bored of spending it trying to mate a horse and a yak to give birth to your own unicorn just for shits and giggles? Why not put that money to use exploiting a corrupt political system?”

“Wealthy people creating and running super PACs to influence election outcomes is common in America—so common that the best way Stiefel has to combat wealthy people creating super PACs is to mock wealthy people using super PACs by … well … using his considerable wealth to create a super PAC.”

political science professor chris cooper

Maybe he’s shouting into a void. But there are some signs that Stiefel is making enough noise to be heard.

During his one-man protest in Raleigh last week, Stiefel ducks inside a coffee shop to warm up. The barista behind the counter eyes his sign.

“That’s the dude who’s trying to steal the seat? That fucker,” says the barista. “It’s hard to keep up with everything that’s going on right now.”

Stiefel agrees.

Over a cup of coffee, he says Americans for Prosparody has proven it can find an audience, and his short-term goal is to make it financially viable so he’s not just pouring money into it.

And as he leaves the shop, a pair of coffee drinkers flag him down.

“Are you trying to be a real judge or something?” the innocent bystander asks, unaware he is falling into the trap of the stunt.

“I mean, apparently nowadays, you can become a judge even if you don’t win the election, you just have to have enough votes thrown out,” says Stiefel. “I’m doing a protest of Judge Jefferson Griffin, are you guys familiar with that case?”

They weren’t—yet.

Support independent local journalism. Join the INDY Press Club to help us keep fearless watchdog reporting and essential arts and culture coverage viable in the Triangle.

Reach Reporter Chase Pellegrini de Paur at [email protected]. Comment on this story at [email protected].