This story originally published online at The Assembly.

Not long after midnight in early October 2023, Lawrence Artis walked across an empty parking lot in one of the many strip malls that have earned Fayetteville a reputation for urban sprawl. The lot is located in one of three high gun violence areas in the city, and just four days earlier, it had been outfitted with the gunshot detection technology ShotSpotter.

As Artis passed in front of the dimly lit storefronts–a Dollar Tree, a discount streetwear shop, a liquidation store, and a plasma donation center where he used to give blood–a squad car approached. Officers had received a notification of gunfire from Artis’ location. Three officers got out and detained him for a search.

Artis, a 29-year-old Black man, was “very anxious when first stopped and handcuffed,” according to the state records on the case.

The officers seized a gun they found in the search, but the records indicate they planned to let Artis go with a warning. A background check revealed that Artis had been convicted of repeat burglary and theft three years earlier. They arrested him for possession of a firearm by a felon. For reasons still unexplained in later investigations, officers missed a second gun hidden in Artis’ pants pocket. That’s when the encounter turned violent. Police claim that Artis, who was still handcuffed at the time, managed to grab the second gun and shoot himself in the head.

He died four days later; it was later officially ruled a suicide. Fayetteville Police Chief Kemberle Braden has maintained the officers heard gunfire moments prior to receiving the ShotSpotter notification and that the technology only “verified what they heard.” Still, the police department has not provided any evidence of the initial gunshot that alerted officers.

Conflicting details about Artis’ final moments have emerged in the 15 months since, but one question has remained consistent: If Fayetteville hadn’t been using ShotSpotter, would Artis still be alive today?

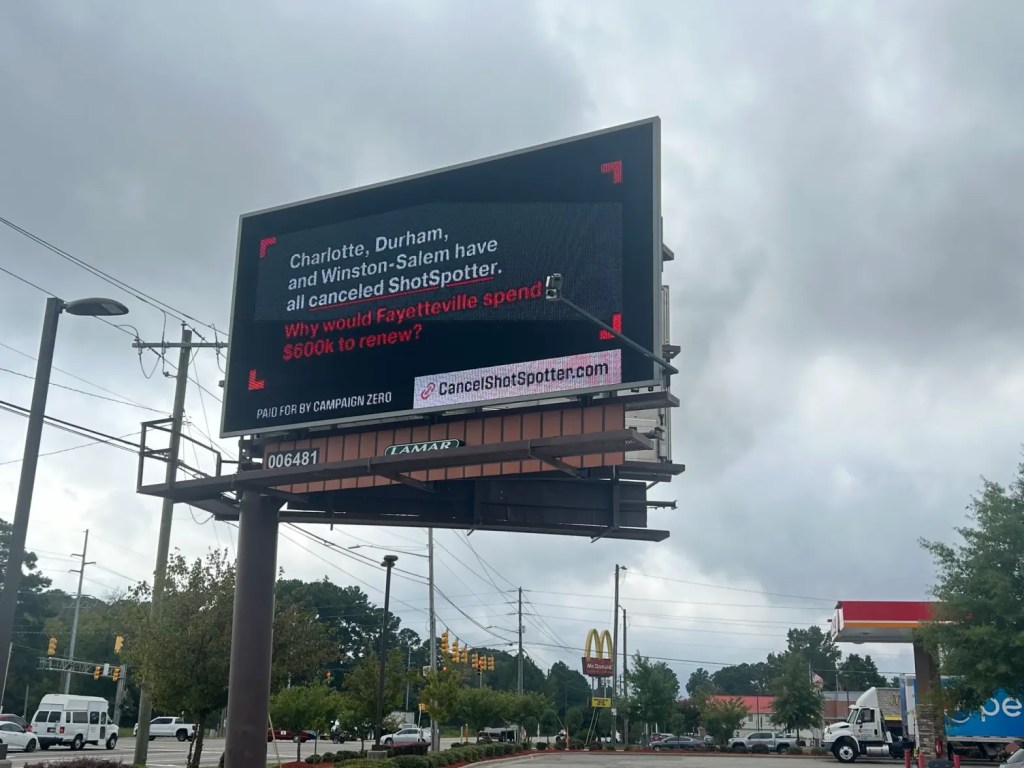

Last September, the Fayetteville City Council voted 6-4 to renew its contract with ShotSpotter for another year, granting $210,000 in funding for continued service. City council members had debated whether to end the contract or renew it for one to three more years.

Those who supported the renewal for three years and voted against a one-year contract declared that the technology significantly contributed to Fayetteville’s decreasing violent crime rate in 2024. One council member claimed Durham’s crime rate had gone up because it dropped the tech, while Fayetteville’s had decreased as a result of keeping it.

Their faith in ShotSpotter, or at least the police chief’s positive assessment of it, was ironclad.

“We assigned him to do a job in the city of Fayetteville,” Council Member Derrick Thompson said. “Why are we not taking his recommendation? Why are we looking outside of what our chief wants? That’s where I’m confused.”

Council Member Mario Benavente, who had proposed the successful motion to study ShotSpotter, criticized other members for not caring “whether it works or not, or whether we’re getting what we were promised.”

Launched in 1996, ShotSpotter is now used in more than 180 communities across the country. The company’s founder thought sensors used to detect earthquakes could also be used to locate gunfire. The technology is in six cities in North Carolina—Fayetteville, New Bern, Wilmington, Rocky Mount, Greenville, and Goldsboro. The company, which changed its name to SoundThinking in 2023, is growing, with projected revenues of $104 million last year and deployment in four new cities and one university. SoundThinking also now sells technology to recognize vehicles and license plates, and to detect weapons, as well as customized versions of the gunshot detection system for highways and college campuses.

At the same time, a number of major cities have ended their contracts with the company, including Chicago, Atlanta, and Portland, Oregon. So have Durham, Winston-Salem, and Charlotte, which endedits $160,000-a-year contract for the technology in 2016 after four years, saying that the “return on investment was not high enough to justify renewal.”

Activists and organizations such as the ACLU say the technology is both ineffective and racially biased, and has led to wrongful arrests and overpolicing in Black and Latino communities.

The company has aggressively defended itself against criticism and says its products are a public safety technology. On its website, the company has a section entitled “False Claims,” detailing what it calls misleading and inaccurate news coverage of ShotSpotter.

ShotSpotter saves lives, said Tom Chittum, the company’s vice president of analytics and forensics.

“We know there’s chronic underreporting of gunfire in urban areas, even when there are gunshot victims,” he said, “and ShotSpotter helps fill that gap.”

A One-Mile Radius

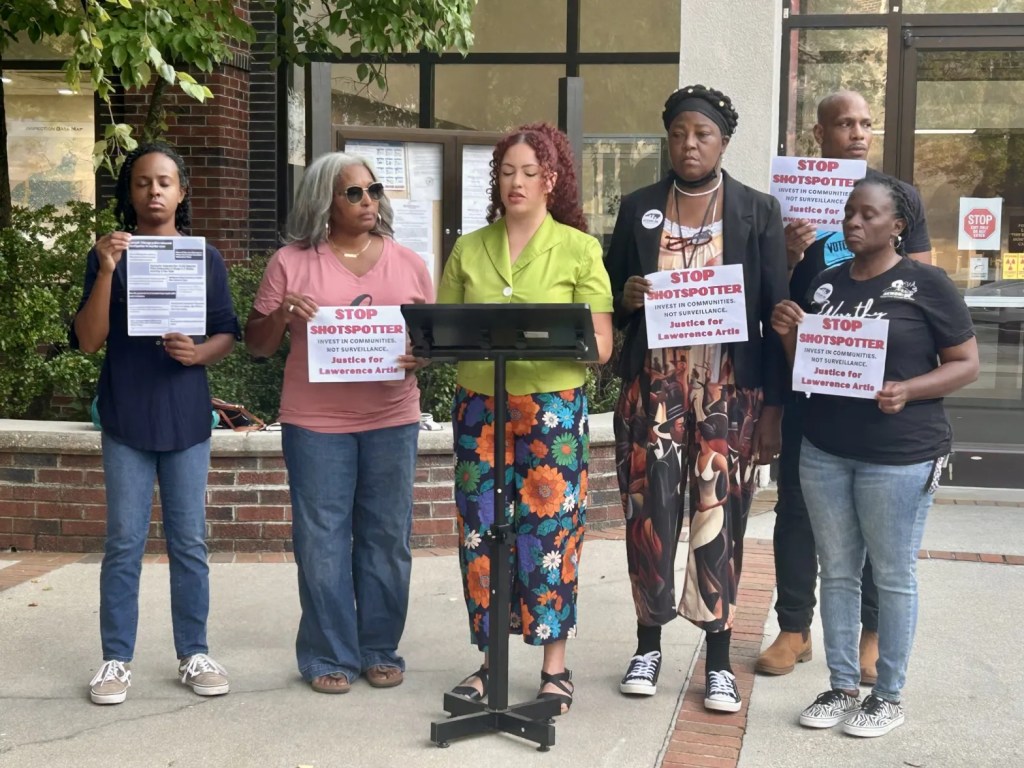

For months after Artis’ death, activists in Fayetteville had raised concerns about the role ShotSpotter may have played. The City Council’s renewal of the contract with SoundThinking last fall brought the subject back into the fore.

Community organizers bearing signs that said “Justice for Lawrence Artis” flooded the September meeting where the council debated the terms of the contract.

ShotSpotter, they argued, can become part of a feedback loop that reinforces existing racial disparities in policing, increasing unnecessary and negative interactions between law enforcement and the predominantly minority communities where the technology has been deployed.

A 2024 Wired investigation into leaked ShotSpotter sensor data covering 84 metropolitan areas and 34 U.S. states or territories found that 70 percent of residents who live in neighborhoods with sensors are Black or Latino.

In Fayetteville, ShotSpotter has been deployed in three one-mile radius zones: around Cliffdale and Reilly Roads in west Fayetteville, in the Murchison Road corridor, and in the Massey Hill neighborhood. The police department has said the locations were chosen based on shots-fired service calls and other gun violence metrics, and that drug and weapons crimes are higher there than the city’s average.

But those areas had poverty rates significantly higher than the city overall, according to a 2023 Economic and Community Development Department analysis.

CityView reviewed the racial demographics in areas that police said they received the most ShotSpotter alerts in the first year of operation and found that eight of the nine locations were predominantly Black, in a city that has a Black population of 41 percent.

SoundThinking’s Chittum dismissed concerns about racial bias and said cities deploy ShotSpotter in locations with the highest historical rates of gun violence.

“It is well-known, very clear, and indisputable that gun violence does not affect everyone in America the same way,” he said. “And I think if you look at ShotSpotter deployments, it is invariably in places where it can do the most good and locate the most victims.”

Fayetteville City Council ultimately approved the $210,000 contract for another year by a vote of 6-4, under the condition there be an independent evaluation and parameters for its success after another year.

“I don’t see where it would hurt us just to have one year and have another opportunity to look at it again and come back and vote a longer term at a later date,” Council Member Brenda McNair said at the time. “It is crucial that we hold these systems accountable.”

Shaun McMillan, an organizer with Fayetteville Freedom for All, criticized the council for not discussing Artis’ case and “their responsibility to prevent the unnecessary loss of life” during debate over the technology.

Braden dismissed concerns about overpolicing in an interview after the vote. ShotSpotter has been a useful tool for the police department, he said, allowing law enforcement to respond faster to dispatch calls and collect useful evidence, especially at a time when there were more than 100 vacancies in the department.

Artis’ case “proves that ShotSpotter works,” he said. “The officers were across the street. They heard the gunfire. ShotSpotter verified what they heard. They go over there, they deal with Lawrence Artis.”

Put To The Test

ShotSpotter started as a bit of an experiment.

Physicist Robert Showen was trying to locate earthquake epicenters at the Stanford Research Institute in Menlo Park, California, when he heard gunshots in a nearby neighborhood back in 1996. He wondered if the same seismographic technology could also be used to register gunfire. With the help of two engineers, he soon founded ShotSpotter.

Over the next 15 years, Showen’s team raised money, developed the technology, and deployed it initially in 20 cities. In 2010, they hired Ralph Clark as CEO. Clark helped establish the Incident Review Center, allowing more cities to adopt ShotSpotter, and took the company public in 2017. Two years later, the company said it had approved the technology’s accuracy and was serving more than 100 customers.

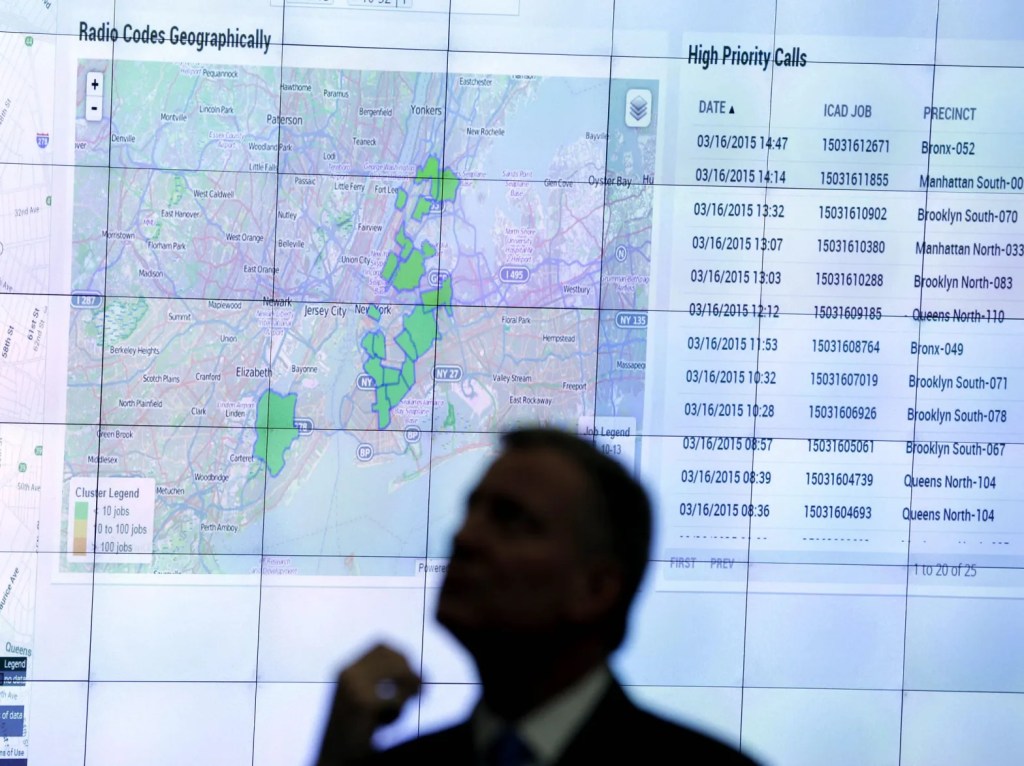

ShotSpotter works by placing an array of acoustic sensors in a designated area. Those sensors are linked to a wireless, cloud-based system that company officials say can send alerts when there are sounds of gunfire. The alerts are sent to the company’s Incident Review Center, where staff assess those alerts and dispatch them to law enforcement agencies. Officers then can respond to those ShotSpotter alerts, where they will locate possible gunshot victims and find evidence of gun violence.

SoundThinking’s main claim is that 80 percent of all gunfire goes unreported. ShotSpotter technology, company officials argue, fills the gap—the technology captures more incidents of gunfire, which means that law enforcement agencies can potentially locate gunshot victims and help put a dent in gun violence.

Critics say ShotSpotter simply doesn’t work; it registers shots where there is no evidence any happened. Accuracy is a major reason that Chicago cited in its decision to discontinue it in 2024.

A report from Chicago’s Office of the Inspector General found that evidence of gunfire was found in less than 10 percent of the 50,176 ShotSpotter alerts in the city between January 1, 2020, and May 31, 2021.

A 2024 audit from New York’s comptroller found that in June 2023, 82 percent of ShotSpotter alerts could not be confirmed when officers arrived at the scene. The audit did, however, find that ShotSpotter improved response times to possible shootings, giving potential shooting victims a better chance at survival.

Brooklyn Defenders, a public defenders office, analyzed nine years of city data and found that the New York Police Department was only able to confirm the accuracy of ShotSpotter in about 17 percent of cases. Out of 75,000 ShotSpotter alerts in the nine-year period, 0.8 percent of them resulted in the recovery of a gun. The city still has a contract, company officials said, but declined to provide further details. (The NYPD is seeking a three-year renewal, but the city has not appeared to have acted on it; The Assembly submitted a public records request with the NYPD, which is pending.)

The company has fought back, pointing to research, including a report on Winston-Salem, that the technology does make a difference. Researchers from the Center for Crime Science and Violence Prevention at Southern Illinois University-Edwardsville produced an initial report and then updated itlast year. The report said that the area in which ShotSpotter was deployed saw a 24 percent decrease in assaults and homicides and that the response time to ShotSpotter alerts is significantly quicker than those called in by residents.

The company also sued Vice Media for defamation in 2021 for an investigative story that alleged police departments asked SoundThinking to alter ShotSpotter alerts. Company officials denied the allegation. A judge ultimately dismissed the lawsuit, but Vice Media and The Associated Press, which ran a piece detailing similar allegations, ran corrections.

Even as some cities have ended their contracts, the company says it wants to continue to work in North Carolina. Whether that means expanding its reach into the state, the company is mum, only saying it was looking “forward to working with other jurisdictions in the state to instrument the same rapid response capabilities to criminal gunfire.”

Chittum, who was formerly with the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, told The Assembly that he was skeptical about the technology when he first joined the company in 2022. But he has since become its most public spokesman. He called criticisms of it inaccurate and misleading, and he argued that academic research–including the report on Winston-Salem’s experience–actually shows the technology leads to law enforcement officers responding more quickly, and that gunfire is detected at higher rates than 911 calls.

Many people have a shallow understanding of how the technology works, he said. Even if police don’t immediately find any evidence at a scene, that doesn’t necessarily mean there wasn’t gunfire, he said. “What we see is that when police go back during daylight hours, they use metal detectors or K-9 to find fired cartridge casings,” Chittum said.

Chittum didn’t offer any specific data on how often law enforcement officers find gunfire evidence the next day. He noted that police might not find any evidence of gunfire after a 911 call either, and no one is demanding to eliminate that service.

The company, however, could not provide much hard data on the number of arrests or convictions that have resulted from ShotSpotter alerts, or how often prosecutors in North Carolina or elsewhere have used ShotSpotter evidence to reach convictions.

The company doesn’t require law enforcement agencies to keep track of certain metrics that might illuminate how effective ShotSpotter is, Chittum acknowledged; while the company encourages law enforcement agencies to track such metrics, the company could not require it in contracts.

“We don’t know about that unless they report it to us,” he said.

Data collection is an issue for many agencies, so the company’s focus is to make things easier for the customer to collect data and share it with SoundThinking, Chittum said.

Durham and Winston-Salem were among the best customers when it came to tracking metrics, he said. That’s why company officials were so stunned when both cities decided not to renew, he said.

Durham and Winston-Salem were “exemplary customers,” he said.

Questions About Efficacy

ShotSpotter arrived in Winston-Salem in 2021, as city leaders concerned about an uptick in gun violence desperately sought solutions.

“Now, more than ever, we want to get a better handle on gun violence,” Winston-Salem Assistant Police Chief Natoshia Miles told the city’s Public Safety Committee in 2021, according to the Winston-Salem Journal.

Miles cited the 2020 death of Jericka McGee, whose body was found on the side of a road. People heard gunshots, she told the committee, but no one called the police.

“We know that if we had had a gunfire detection system in place, we would have been immediately dispatched to that particular location, possibly getting her life-saving measures in place, and maybe even saving her life,” Miles said.

The Winston-Salem City Council voted unanimously on January 4, 2021, to approve a three-year contract with ShotSpotter, using nearly $700,000 in federal grant money to fund it. The deployment was limited to a three-square-mile area northeast of downtown that is predominantly Black and poor. At the time, Council Member Robert Clark, chairman of the city’s finance committee, wondered if the city was getting the most for its money. He pointed out the area was a mere 2 percent of the city.

But city officials seemed pleased with ShotSpotter in the early days and even featured it in a 2022 video where a police officer talked about how it led them to a gunshot victim bleeding in a field. Without the technology, the officer said, the man would have died.

After that initial three years, however, the technology’s efficacy remained unclear. According to Winston-Salem Police Department statistics, officers responded to 3,935 ShotSpotter alerts over three years. Officers found no evidence of gunfire and no witnesses 54 percent of the time.

Between January and July 23, 2024, officers responded to 628 ShotSpotter calls. They found no gunfire evidence in 65 percent of them.

Winston-Salem Police Capt. Michael Knight told WGHP/Fox 8 in August that they didn’t think renewing the contract was worth it.

“A lot of times, we are going out there without a corresponding 911 call, and we are walking around looking for a shell casing,” he said.

City officials pointed to financial reasons for why they were not renewing the contract: “After conducting a cost-benefit analysis of all technology used by the WSPD and evaluating our budget, we have decided not to renew our contract with ShotSpotter.”

The company sent a letter to Winston-Salem officials last August asking them to reconsider. “Over the past three years, our relationship with the City has been strong, and as a result, we were surprised and disappointed to learn that WSPD intends not to renew its relationship with SoundThinking came in the form of the August 2 media report,” wrote CEO Clark. “More troubling, though, is the news report and related statements that contain inaccuracies and mischaracterizations made by media outlets regarding the positive impact our services have had in Winston-Salem.”

City officials never responded to the company’s letter, and Annie Sims, the spokeswoman for the police department, said that neither Police Chief William Penn nor any other police official would be available for an interview.

The city of Durham made a similar call amid tensions about how to reduce gun violence. As advocates rallied for more investment in programs that address the systemic problems that can lead to criminal activity, the city council voted twice against funding ShotSpotter. But in June 2022, the council voted 4-3 to include $200,000 in its budget for a one-year pilot covering a three-square-mile area of East Durham.

The Durham Police Department said it would measure the pilot’s success, including an independent external review conducted by the Wilson Center for Science and Justice at Duke University.

The results of that study were mixed. It found that Durham police received 1,447 notifications of gunfire in the pilot area over the 12-month period from December 2023 to December 2024: 57 percent were ShotSpotter alerts with no corresponding 911 call, but only 9 percent of those ShotSpotter-only alerts resulted in confirmation of a shooting.

The report also showed that ShotSpotter reduced police response times in the pilot area by an average of 1.2 minutes. Overall, the Wilson Center could not definitively say whether the pilot had led to reduced gun violence.

During a postmortem at a March city council meeting, Councilmember Javiera Caballero accused SoundThinking of “shifting the goal posts” in how it represented their ShotSpotter technology, focusing on the promise of quicker response times rather than reducing gun violence overall.

“I will not argue the data,” Caballero said. “But to change the argument around your tool so that you can sell it better is dishonest and not fact-based.”

Durham voted 4-2 not to renew its contract with SoundThinking last March.

Happy Customers

In Wilmington, SoundSpotter’s presence has been much less contentious.

The city first started using the technology in 2011, an early adopter along with Rocky Mount, which also continues to use the technology. Wilmington’s City Council hasn’t publicly discussed its contract with the company since a presentation in 2019. That meeting sparked only a brief discussion, in which now-former Police Chief Ralph Evangelous presciently noted, “We’re really starting at the dawn of AI.”

In addition to the gunshot-sensing technology, that year Wilmington became the first agency in the country to implement Missions, ShotSpotter’s AI-driven crime-forecasting tool. Missions uses historical crime data to predict when and where crimes may occur, and it generates patrol recommendations based on its forecasts.

After implementing Missions, the department made it a policy that each officer must follow at least two AI-generated patrol recommendations per shift. “Call volume and staffing levels can and do influence how often officers are able to perform this,” spokesman Brandon Shope told The Assembly.

ShotSpotter’s acoustic sensors cover at least six square miles, with the highest concentration of serious crime rates around downtown Wilmington, the department has previously disclosed. The department declined to address the sensors’ general location or coverage radius when recently asked by The Assembly.

“I wasn’t convinced [ShotSpotter] was going to work,” Evangelous told Council. “And it far exceeded our expectations.”

The Wilmington Police Department renewed ShotSpotter’s three-year contract in 2022. ShotSpotter’s contract this fiscal year is for $433,000, according to a city spokesperson.

The AI assignments give officers various tasks to prevent crimes, like parking their cars to perform paperwork or taking a walk in areas where the software predicts crimes are most likely to occur next. In promotional materials, ShotSpotter says the system helps departments eliminate bias by using data over what was previously officers’ instinct for where and when to patrol.

Wilmington officers gushed to Forbes in 2021 about ShotSpotter’s capabilities, but there were some holdouts getting everyone on board: “Most officers don’t like change,” Deputy Chief Alex Sotelo said. “They feel that nothing can tell them how to do their jobs better.”

Shope said the department isn’t able to estimate how many lives the technology has saved but called it an invaluable tool. “The presence of this device is also a great deterrence for illegal gun crimes within city limits,” he said.

Shope said the department can’t disclose much about where and how they are using the technology “due to security reasons” and said they couldn’t comment on other agencies’ decisions to stop using the technology.

Hard To Measure

Even after more than a year, many questions about Artis’ death remain. The State Bureau of Investigation completed its probe by early 2024, and Cumberland County District Attorney Billy West stated in July 2024 that there would be no charges against the three officers.

While the names of the three officers have been made public, the Fayetteville Police Department has refused to state whether they are still on the job. The officers were initially placed on administrative leave.

“Per personnel records, we cannot release any information regarding an administrative investigation, as this would be a violation of personnel laws,” said a spokesperson.

In late November, the North Carolina Office of the Chief Medical Examiner released its ruling that Artis’ death was a suicide. But conflicting details within the police accounts, the autopsy report, and the state medical examiner’s investigation have left community activists with more questions than answers.

At a Fayetteville City Council meeting in January, city staff said the city has engaged the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute to do a qualitative analysis of the ShotSpotter zones, which will look at underlying issues contributing to the high gun violence rate in the areas, including food and housing insecurity. The study will be used to develop strategies to reduce gun violence—the stated goal of ShotSpotter in the first place—as part of Fayetteville’s new Office of Community Safety.

“The results of this analysis, including recommendations for violence reduction, will help to provide a data-driven basis for moving forward with programming recommendations,” the city said in a statement.

Benavente, a criminal defense attorney and strong opponent of ShotSpotter, pointed to the lack of evidence linking Artis to the detected shots. In 2023, he made the motion that city council study the root causes of gun violence in ShotSpotter zones. In approving the new contract, Benavente argued that his colleagues didn’t care about addressing the systemic issues facing those in the ShotSpotter areas.

“We have that study that is coming back to us before the end of the year with the prescription,” Benavente said in an interview. “But until they get it, they don’t want to give up their empty calorie bag of chips on the promise of a chicken dinner, until they get the chicken dinner. And they’re just not making the connection that, like, ‘Well, we got to make that plate available.’”

At a meeting of Fayetteville’s Community Police Advisory Board last November, Assistant City Manager Jeffrey Yates gave more details about plans to evaluate the ShotSpotter program over the next year. Yates said the city is working with the Wilson Center at Duke–the same group that evaluated Durham’s program–to “put together a scope and to have them take a statistical look at the ShotSpotter data.”

He echoed a common refrain of city officials who support ShotSpotter–that it’s a “tool in the tool belt” of public safety, even if studies in places like Durham have found inconclusive results.

“It’s hard to prove a negative,” Yates said. “It’s hard to measure the things that didn’t happen.”

Michael Hewlett is a staff reporter at The Assembly. He was previously the legal affairs reporter at the Winston-Salem Journal. You can reach him at [email protected].

Justin Laidlaw is a staff reporter at INDY Week. You can follow him on X or reach him by email at [email protected].

Johanna F. Still is The Assembly‘s Wilmington editor. She previously covered economic development for Greater Wilmington Business Journal and was the assistant editor at Port City Daily.

Evey Weisblat is a reporter at CityView. She has previously worked at papers in central North Carolina, including The Pilot and the Chatham News + Record. Her central beat is government accountability reporting.

Comment on this story at [email protected].